| 3 |

Port Swettenham from 1900 To 1909 |

The origin of this port was the necessity of having a port for the State to which ocean-going steamers could come. It was impossible for large steamers to come up the winding Klang River in which, at spring tides, a current of 5 or 6 knots runs. It was, therefore, decided to make a port at the mouth of the river, and work was begun on 1st January 1896. The port was to be called Port Swettenham; it permitted of the entry of ocean-going vessels.

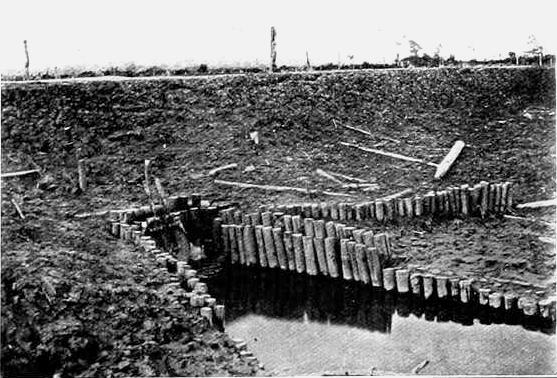

The land at the spot chosen was very low-lying mangrove swamp, which was covered at all spring tides to a depth of 2 or 3 feet by the sea. In the higher tides, especially at the September equinox, the tide floods the land for a distance of a mile inland.

The railway was carried along the fore-shore on an embankment, and wharfs were built connected with the embankment. No attempt was made to reclaim the land; and the workmen, during the construction, lived in huts raised on posts above the swamps after the Malay fashion.

| 3.1 |

Port Swettenham in 1901 |

When I assumed duty at Klang in January 1901 the wharfs were practically completed, and only the finishing touches were being given to the station buildings. There were few inhabitants in the place, and there were few cases of malaria; but I observed that new arrivals quickly became affected. I also heard there had been a considerable amount of malaria among the workmen formerly employed there. The place was practically a mangrove swamp in which about fifteen acres had been cleared. No attempt had been made to reclaim or drain it, and it was full of anopheline breeding places.

It was obvious what should be done. In February 1901, at the suggestion of the Klang Sanitary Board, the resident engineer began to clear the land, fill in holes, and generally improve the land as far as his votes permitted. There was, however, no money available for a proper scheme.

On the 20th April 1901, at the request of the Acting State Surgeon, Dr. Lucy, I forwarded a report with recommendations. These included, in addition to ordinary sanitary measures:

- Clearing and levelling the Government Reserve and putting it under grass.

- The filling in of abandoned drains.

- A complete scheme of drainage.

- The notification and, if considered necessary, the removal to hospital of cases of malaria.

- Experiments with mosquito netting and quinine on certain sections of the population.

In urging these recommendations, I expressed the opinion that the “Government Staff shortly to be stationed there will be seriously affected and their services much impaired.”

That such was necessary was obvious; and Government put $10,000 on the estimates for 1902.

| 3.2 |

Opening of the port |

On 15th September 1901 the port was opened; and the Government population and the coolies connected with the shipping were transferred from Klang to Port Swettenham.

| Days after Arrival | 9–18 | 19–28 | 29–38 | 39–48 | 49–58 | 59–68 | 69–78 | 79–88 |

| No. of cases | 13 | 12 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 8 | 1 |

Fearing an outbreak of malaria, and desiring to have a record if such occurred, I had a register started of the Government population, showing for each person, name, age, previous history of malaria, date of arrival at Port Swettenham, date of attack, date seen, nature of parasite, if sent to hospital or not, date of return to duty, remarks. Each house had a separate page. This was completed within a few days of the opening of the port by Mr. R. W. B. Lazaroo, the Deputy Health Officer; and in order that I might have as complete a record as possible, this officer visited each of the Government quarters. This registration was continued for some years, and by this means cases were properly treated from the beginning and removed, if necessary, to hospital.

As far as possible all officers were sent to hospital, and to remove one of their objections to this, Government allowed at my request the recovery of travelling expenses on the certificate of the Medical Officer. These precautions had the happiest results in the saving of lives, as will be shown hereafter.

| 3.3 |

The outbreak |

Immediately after the port was opened malaria assumed an epidemic character. In less than a month the 180 leading coolies were so decimated by disease that the remnant refused to live any longer at the port, and returned to Klang. Two other batches (about seventy each) were imported on the 10th and 20th October respectively, and were lodged in separate houses in Klang. Klang, however, was then in the throes of the epidemic foreshadowed by the great sickness in the early part of the year, and these coolies suffered so much that the majority left within a month. The leading contractor had then to employ Tamil coolies from a coffee estate. The Government population also suffered severely; out of 176 persons, including the crews of the Government yachts and launches, no fewer than 118 were attacked between 10thSeptember and 31stDecember (see Table 3.1).

Two months after the port was opened I visited the native houses which had been built; of the 127 inhabitants 78 were said to have been attacked, and 25 of the 27 houses were infected.

The effect of the disease on the business of the port was very serious. Ships came in and could not unload. Those on fixed runs had to over-carry cargo. The crews contracted malaria, and after a month or so it was impossible to obtain a crew willing to trade to the port. The Harbour and Railway Departments were so crippled that they could only imperfectly do their duties, and so utterly demoralised did the port become that the High Commissioner ordered the closure of the port until it could be made more sanitary. To go back to Klang was out of the question, and Government advised the trial of the recommendations of a Commission,4 which in the meantime had been appointed.

| 3.4 |

Work done in Klang |

The Commission advised the measures which I had recommended in the previous April, and within six weeks the work of the port was proceeding without great difficulty.

An area of about 100 acres was bunded, drained, and freed from jungle. All possible mosquito breeding places were oiled freely. Quinine was systematically given to all who would take it, and most did. The outbreak had so much diminished by the time information about wire gauze was received, that none was ever required.

| Year | Item | Strait Dollars |

| 1901 | jungle clearing, drain cutting, forming bunds | 2,000 |

| 1902 | filling in, tide flaps | 27,999 |

| 1903 | felling and clearing jungle | 2,563 |

| brick drains | 1,180 | |

| 1904 | felling jungle, filling in, etc. | 12,311 |

| brick drains | 1,541 | |

| 1905 | clearing scrub, etc. | 1,469 |

| brick drains | 1,022 | |

| concrete drains | 2,275 | |

| Total | 52,360 |