| 21 |

The malaria of rivers |

| 21.1 |

Rivers in tidal zones |

Rivers differ greatly in different countries; the same river in the same country may pass through different zones of land; and in any zone it may alter its character to become narrow and swift, or broad, swampy, and sluggish. So in considering the malaria of rivers, it may make the subject clearer if I take a river at different points of its course and discuss its relation to malaria.

| 21.1.1 |

Tidal and brackish rivers |

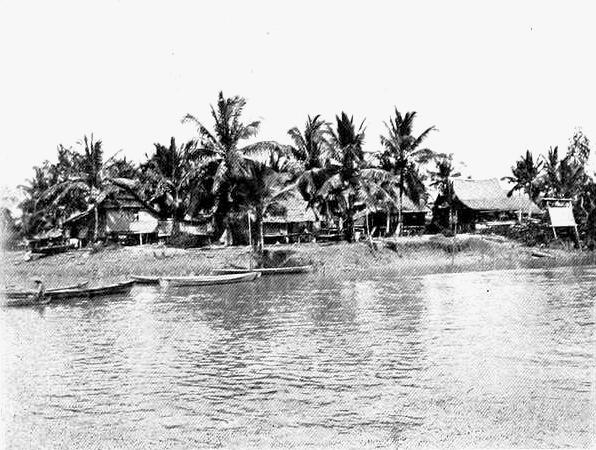

This is really the zone of the mangrove swamp and A. ludlowi, with which I deal in Chapter 9. The river has a muddy bank, fringed with mangrove, while behind the mangrove comes the swampy Coastal Plain. Mosquitoes do not breed in the river bank itself; nevertheless, the banks of a river in this land are intensely malarial, unless a thorough system of drainage is constructed. How unhealthy it can be is seen from the early history of Port Swettenham and from the cocoanut estate mentioned in Chapter 9; how healthy it can be made is shown by the estates on Carey Island.

| 21.1.2 |

Tidal, non-brackish rivers |

With so large a rise and fall of the tide (some 16 feet) as occurs in this part of the Straits of Malacca, the tidal wave passes fully 20 miles up the rivers as they twist and wind through the Coastal Plain.

In the upper reaches of the river the water is no longer brackish; and here, as in the lower brackish reaches, no larvae are to be found on the river’s bank; but the land through which it passes is malarial from A. umbrosus—the inhabitant of the Coastal Plain. In Chapter 8 we saw how healthy this can be made; for example, Estates “OO,” “TT,” and “HH.”

| 21.2 |

Rivers with swampy banks in the A. umbrosus zone |

Beyond the tidal, but non-brackish, portion of the river, we reach a part where the character of the land through which the river runs is still the important factor in determining the presence or absence of malaria. Where the river course is not well defined, or the banks are very low, there may be a permanent swamp that will be dangerous from the presence of A. umbrosus. These swamps may be of great extent; almost certainly they cannot be efficiently drained; to “fill” them with earth would cost a King’s ransom. The simplest way to make a people healthy in such a place is to move them back from the river swamp a distance of half a mile or more. The following is an example of the problem that may be met.

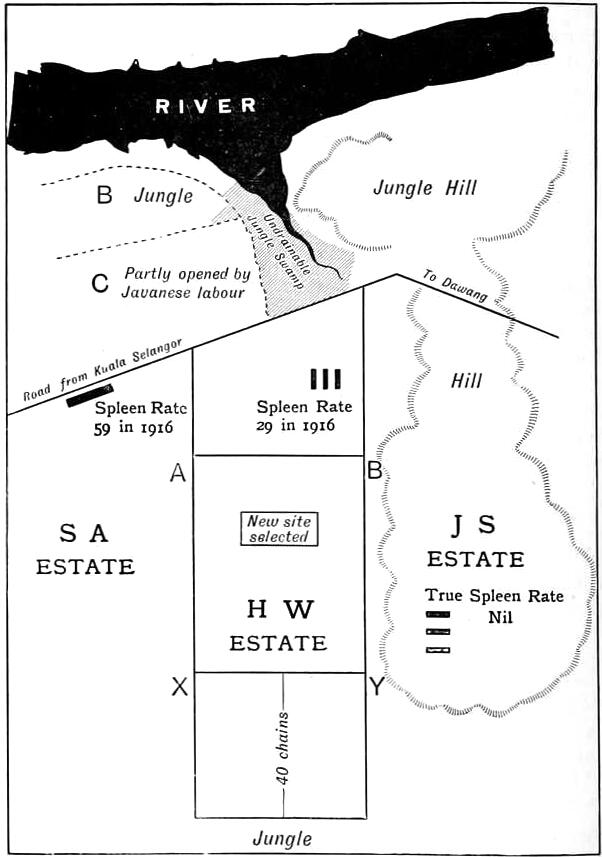

Three Estates, “SA,” “HW,” and “JS,” are situated together on a Government road (see Figure 21.3). Estates “SA” and “HW” are rather above the level of the Coastal Plain; they are not dead level, yet would not be called undulating land. The drainage is good. Estate “JS” is definitely hilly, or rather a hill or island, for it is almost everywhere surrounded by lower land; there are no ravines, and no A. maculatus. In 1915 the health was good, the true spleen rate being nil; the only death in a labour force of 114 was that of a child.

Estate “SA” had been unhealthy, the spleen rate of twenty-seven children, examined in January 1916, being 59%. The coolie lines were situated about 100 yards or less from the road, on the opposite side of which was a piece of flat land which Javanese had begun to cultivate, but which until a few months before had been under jungle. Thinking it probable that the opening of the Javanese land would improve the health of Estate “SA,” without the estate having to do anything, I recommended no action be taken with regard to the site of the lines. The fact that the labour force looked so much healthier than I expected, from the spleen rate of 59%, suggested that the improvement had already begun.

Estate “HW” was also unhealthy. The spleen rate in January 1916 was 29% out of thirty-seven children, which was lower than that of Estate “SA.” The reason for the difference was that whereas the lines on “SA” were close to the road and within 5 chains of undrained jungle, the lines on “HW” were 20 chains away from the road, and so farther from the breeding place of A. umbrosus.

When, however, I came to consider how to bring down the spleen rate on “HW,” the matter was not so simple as on “SA,” where my recommendation was to do nothing. The jungle opposite “SA” had been drained, and was being cultivated by the Javanese; the jungle opposite “HW” was undrainable and could not be cultivated, as we found on visiting it.

As the lines were within 20 chains of this swamp, and I advise 40 chains as a minimum, it was necessary to inquire if a better site could be obtained elsewhere. Behind the estate was jungle; so that the site could not be within 40 chains of the back boundary or south of the line XY; there was swamp across the Government road, so the site must be at least 40 chains in or south of the line AB. The east boundary, being “JS,” was harmless, being hill without ravine; the west boundary was “SA,” and no dangerous Anopheles were found in it. So there was the area ABYX within which the site might be. A local examination led to the selection of a slightly raised portion of the land. In May 1916 I made these recommendations in writing; the report was sent to the Directors in England, who at once cabled their approval, and by September the new lines were finished and all the coolies removed, at a cost of $7000.

On both estates the health improved, as was anticipated. On Estate “SA,” where the lines remained in the original spot, the jungle swamp was removed through the Javanese cultivation, the spleen rate was reduced (Table 21.1).

| Estate | Date | No. examined | Spleen rates (%) |

| HW | January 1916 | 37 | 29 |

| November 1917 | 46 | 15 | |

| June 1920 | 44 | 9 | |

| June 1920a | 41 | 4 | |

| SA | January 1916 | 27 | 59 |

| November 1917 | 84 | 2 |

- a

- True rate

In 1917, of the two children with enlarged spleen, one was an old resident; the other, a recent local recruit. Out of the whole labour force of 340 mustered for inspection, there was only one case of slight anaemia and one case of fever. The whole force was in splendid health; and it was apparent that the health had begun to improve as soon as the land opposite was opened, and before my inspection in January 1916, as I had surmised.

On estate “HW” the coolies had not been so long removed from the malarious influence as on estate “SA”; for it was September 1916 before they were removed. But even they had improved in health (Table 21.1).

| 21.3 |

Rivers still farther inland |

To decide upon the right method of dealing with a river swamp, especially in a large town, is not by any means always a simple matter, as the next example shows.

| 21.3.1 |

The Batu Road swamp |

This swamp was situated in the centre of the town of Kuala Lumpur, the capital town of the F.M.S. It lay between the river and a row of houses, the sewage of which discharged into the swamp; there were no sewers to convey it to the river. For days at a time the swamp was flooded.

The Sanitary Authority rightly decided to take action to abolish this foul swamp; and issued an order to the owner requiring him to fill it with earth to such a level that it would not be covered by the majority of floods—the filling to be to over “average flood level.” The engineer for the owner estimated this would cost $61,677 (as a matter of fact the level given by the Sanitary Authority was incorrect, and the cost would have been considerably less, as was discovered afterwards). In view of this large expenditure, I was asked to advise on what was necessary to prevent the swamp being a nuisance.

The swamp was not a cause of malaria in my opinion; and Dr. Strickland, who examined the houses next to the swamp, confirmed this. He found “only one child with any enlargement at all (of spleen) out of twenty-five.” Nevertheless, it was a foul spot, which was breeding many mosquitoes.

The level to which I thought the land should be filled was about 11/2 feet above swamp level; and I regarded swamp level as fixed by the lowest level at which the sensitive plant, Mimosa pudica, would grow. Part of the ground was dry, covered by M. pudica, and not suggestive of swamp; part was frankly swamp, being covered by water; while other parts were dry at the moment, and not covered by M. pudica.

All around there was a well-defined line at which M. pudica stopped growing, and below which the vegetation consisted of bulrushes and swamp grasses. I regard the mimosa line as the level of the swamp water or permanent ground water, because M. pudica cannot grow in a swamp. It is a leguminous plant with nitrogenous nodules on its roots. These nodules absorb nitrogen from the air, and, therefore, must be in what normally is dry soil.

An engineer with a theodolite took levels at widely different parts of the swamp, when I set the staff on the line of the M. pudica. The readings (using his own datum) were curiously consistent: 42.51, 42.49, 42.33, and 42.12; the river level, on March 10th 1915, was found to be 40.21.

My advice was that the whole ground should be filled to the level 44, which was fully 11/2 feet above the mimosa level. The cost of filling to the level 44 was estimated by the engineer at $2324; a difference of over $59,000 from what was required by the Sanitary Authority. In view of this evidence the Sanitary Authority obtained a report from another engineer, who said: “The level of the line between mimosa and swamp grass noted by Messrs. Mace, Hall, & Co. as being quite distinct, was ascertained in the vicinity of the large patch of low-lying ground in the centre of Lot 11.” The elevation levels on 9th May 1915 were as listed in Table 21.2.

| Reading | Reduced level from town datum |

| 4 | 85.90 |

| 5 | 86.20 |

| 6 | 85.80 |

| 7 | 85.20 |

| 8 | 85.20 |

| 9 | 85.80 |

| 10 | 85.90 |

| Average | 85.70 |

It was evident from the readings of the two engineers that the mimosa line was something definite, and could be fixed with sufficient accuracy to justify action being taken on it. The line being fixed, and the cause of the line—the depth of dry soil in which the mimosa roots would grow—being indisputable, the Sanitary Authority adopted my suggestion of basing the amount of “filling” on the mimosa line.

I have discussed this question at some length; but not more than it merits. Riverine swamps occur in many places, and in many towns. In Kuala Lumpur there are many acres, part belonging to Government, and part to private owners. To fill them one foot per acre more than is necessary would lead to great waste of money, whether the money be that of a private individual or of Government.

| 21.4 |

Inland plains |

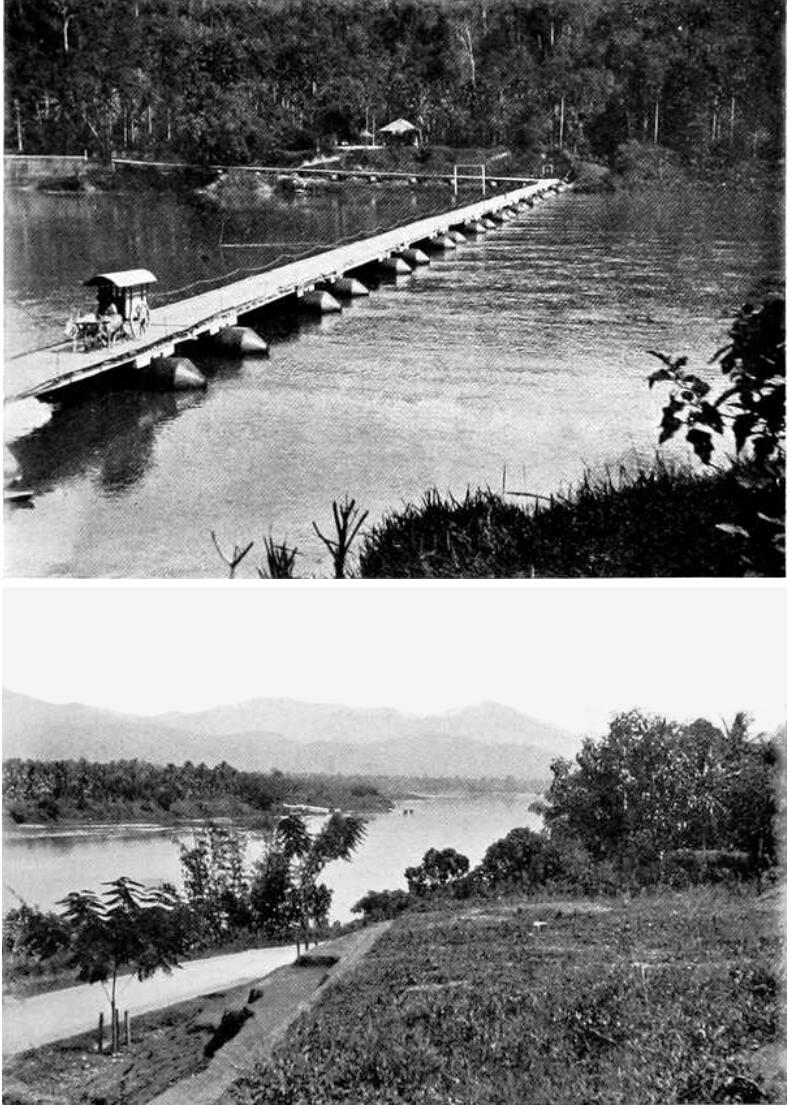

It is on the banks of the larger rivers that we find the representative in this country of the “Inland Plain”; for it is on too small a scale to furnish examples of ancient lake beds or plateaus much above sea-level. Still there are some stretches of inland flat land, and they are healthy. As an example I may give the spleen rate of an estate a few miles beyond Kuala Lumpur, on the river of which I have just been writing. The estate, or at least the portion of it next to this river, has had a reputation for its good health for many years, and the spleen rate justified it. On 26th September 1911, I examined twenty-seven children, all of whom were free from enlarged spleen.

It may be said generally of the larger rivers in this country that they are non-malarious; by which I mean that where the banks are well defined, dangerous anopheline larvae will not be found in any quantity in the vegetation that may grow on the bank. Where the river bank is not defined, but loses itself in a swamp, the health depends on the zone of land in which the river is situated; if in the umbrosus zone, the swamp will be dangerous; if farther inland and A. umbrosus is not present, it will be harmless, unless A. aconitus is breeding in it. In 1909, I recommended the removal of coolie lines from ravines to the banks of another river with entirely satisfactory results.

| 21.5 |

The smaller rivers |

As one passes still farther towards the source of a river, and before the small ravine streams are reached, one finds a stream perhaps some 20 feet wide and a foot or so deep, pursuing a rather tortuous course down an inland valley. The river is clear, the bottom sandy, the sides grassy.

Along the grassy banks are found the larvae of A. maculatus; they are also present in side pools along the river. In heavy rain, the stream becomes a raging torrent; in dry weather, a sleepy stream; but always too big to be put underground in subsoil pipes. If malaria exists in such a community, how can it be eradicated?

| 21.6 |

Tarentang Estate |

In 1912 I was asked to advise this estate, as malaria had been severe; and I found there the problem described above; with the complication that many small ravines, breeding A. maculatus, ran through the estate and discharged into the river. The banks of a clear stream are attractive sites for coolie lines, and in many places throughout the country have been selected as headquarters for a labour force. If such sites could be made healthy, it would be an advantage to the whole country to know how it could be done. If it were impossible to make them healthy, no less valuable to everyone would be the knowledge; for then these sites could be avoided in the future, or abandoned if already in use.

It appeared to me that the procedure to be adopted should be experimental; and, as such, a portion of the cost might fairly be borne by Government. Accordingly I suggested an experiment both to Government and to the estate; and both agreed to share the expense equally. My idea was to render the ravine streams harmless by subsoil drainage, and to oil the edges of the main stream. Unfortunately there appears to have been a misunderstanding of what I required; and on my next visit to the estate in 1914, I found not only the ravines being “piped,” but an entirely new channel being made for the main stream, at, of course, a much heavier expenditure than all the ravine drainage put together. The Government labour employed on the drainage had been decimated by malaria; the engineer in charge had been laid up so frequently that proper supervision had been impossible; and the work was not satisfactorily carried out.

A. maculatus still breeds in side pools in the bed of the main stream in dry weather, and although the health has improved, the unhappy experiment has not been carried far enough to warrant any final conclusions.

The course of a river has now been traced from the sea backwards almost to its source in the hills; probably in some ravine. Of ravines and their malaria I have already written in the chapters on Seafield Estate; so, for the present, shall say no more. But before closing I must reprint Dr. Strickland’s unpublished paper on “The mosquitoes of stream courses”, which sums up the results of his extensive research.

| 21.7 |

The mosquitoes of stream courses, by Dr. Strickland |

Of course, at the eye of a stream, exactly where the stream-course resolves itself from out the swamp from which it springs, it is impossible to say. Sometimes, however, especially in the dry weather, the stream commences as a series of pools in a definite well-cut course, and such places I have included here, although there be no semblance of a stream through the pools. I do not include flooded land as being in a stream-course.

The species that I have taken from stream-course are listed, from first to last, in Table 21.3. This table shows the very marked predominance of A. maculatus over the other species in this respect, and justifies the appellation usually given to it of a stream-breeder, originated by Watson.

| Anopheles species | Abundance (‰) |

| maculatus | 340 |

| barbirostris | 153 |

| sinensis | 127 |

| aitkeni | 67 |

| karwari | 60 |

| kochi-tesselatus | 60 |

| albirostris | 53 |

| umbrosus group | 47 |

| fuliginosus | 40 |

| rossi | 40 |

| leucosphyrus | 13 |

| ludlowi | 0 |

One very common characteristic about a stream course is the absence of grasses at the edge, probably due to the scour. That may account for the comparative absence of A. albirostris, which otherwise would like the swift current. We will mention a few types of streams and their mosquito fauna.

- Tidal rivers and streams. Along these is usually nipah palm and mangrove. The highest spring tides will sometimes leave pools of water among the nipah roots, and occasionally one can find A. umbrosus in such pools. If the vegetation is within reach of the lowest range of tide, nothing can be found. It will be noted in the table that A. ludlowi was never taken from a stream course.

- Small streams running slowly through jungle. At the edge among fallen timber may be found species of the umbrosus type.

- Larger streams running through jungle, like the Batu Pahat river or the Sungei Jembulang. The jungle trees form a dense canopy over the edge of the stream, and the current is strong and deep enough to keep the edges clear of flotsam and jetsam. Consequently, no breeding places are found.

- Scouring out pockets in the banks. This is the home of maculatus and barbirostris, sometimes fuliginosus and aitkeni, e.g. Jementah Estate, Johore.

- Small ravine streams under jungle. The stream is usually difficult to define; the whole is rather a streaming morass. I have recorded aitkeni and species of the umbrosus type in such places.

- Great streams like the Kelantan river. Such are nearly all opened up, unless the hills which come to the edge are too steep for Malay kebuns.44 In any case, nothing can be found along the banks, except in the interesting case of a terrace of the river bank, showing a seepage swamp. In such a place at Kota Bharu, Kelantan, I obtained kochi.

- Mountain torrents. It may be taken that no mosquito lives actually in the torrent, but only in pools along the course, or in silted-up pools. I have there taken leucosphyrus and rossi, while in pools among granite boulders I have obtained maculatus, leucosphyrus, aitkeni or, if the jungle covers such places, only aitkeni.

- Certain streams tributary to great streams like the Kelantan or Pahang, which have reached the base level of erosion, and that [have] a muddy base, have umbrosus species growing in them, if under jungle, or kochi and maculatus, if exposed.