| 18 |

Some other examples of hill campaigns |

It is impossible, in the space available, to give details of all the hill estates upon which I have been asked to advise, and for which I have suggested health areas. Not all, by any means, have been successful. At the beginning, before I could speak from experience, the area suggested was 20 to 30 chains in radius for pipe drainage. This is not sufficient in most places to eradicate malaria, although it will improve health. It is clear now that in dealing with A. maculatus, probably the most efficient carrier of malaria in the Peninsula, and where that mosquito is present in large numbers in much broken hill country, an area of at least 40 chains in radius is required. It must either be drained by pipes or oiled.

| 18.1 |

Failures and successes |

Another cause of failure was the difficulty some managers evidently had in grasping the right way to lay the pipes, and in learning how to look after the ravines once they were drained. In some places where damage done by storm water was not repaired at once, the whole system became blocked by silt, or it was extensively torn up. The early days had its quantum of scoffers: oiling they sneered at; naturally they took little interest in or care of an engineering system which calls for both intelligence and diligent supervision. Under such, anti-malaria measures made little progress, or were failures.

It was no small disadvantage that after starting a scheme in some distant part of the Peninsula, I could only visit it at long intervals, and so was unable to supplement what was sometimes deficient in the manager.

But ten years have passed since I pointed out the special difficulty of anti-malarial work in hill land; both subsoil drainage and ravine oiling have proved themselves capable of controlling A. maculatus and its malaria; each year sees their extended use; indeed, on few malarious estates are anti-malarial measures of some sort not in force; and the result is seen in the general lowering of the death rates of estates throughout Malaya.

In this chapter I propose to give simply the plans of several estates, with, in a few instances, remarks on the reasons which guided the selection of the health area. They may be of use to those called upon to deal with similar conditions.

| 18.2 |

Glenmarie Estate |

This is one of the oldest estates in the country; it has always been malarious. Indeed, so much did malaria trouble it, that a former proprietor built “Turkish baths” in order to “sweat” fever out of coolies. It was only tried once, as the coolie was brought out dead. The building still remains—as a motor shed.

| 18.2.1 |

The selection of sites |

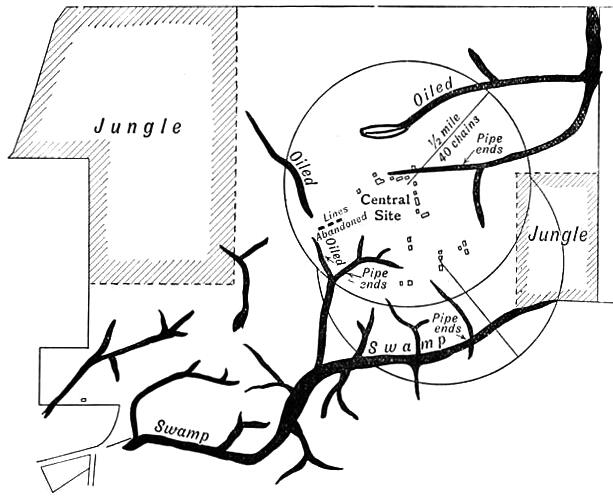

To improve health, a number of lines were abandoned in 1911, and all were concentrated on a central area (see Figure 18.1). At first some 20 chains were drained by pipes; the work was excellently done by Mr. Solbe. It produced a marked improvement in health, and enabled the estate to establish a force of Malayalees, a tribe of Indians highly susceptible to malaria, and one which cannot live in untreated ravine land. The 20 chain area did not, however, give the required result, so in 1917 the area was extended, partly by piping, partly by oiling ravines. Health still further improved, so that in 1919 the average monthly malaria admission rate was 3%. Table 18.1 shows the death rates.

| Year | Death rate (‰) | Year | Death rate (‰) |

| 1910 | 168 | 1915 | 51 |

| 1911a | 126 | 1916 | 40 |

| 1912 | 103 | 1917b | 65 |

| 1913 | 51 | 1918c | 173 |

| 1914 | 59 | 1919 | 35 |

- a

- Subsoil drainage begun

- b

- Drained area extended

- c

- Includes influenza, 47 deaths

| 18.3 |

Estate “JM” |

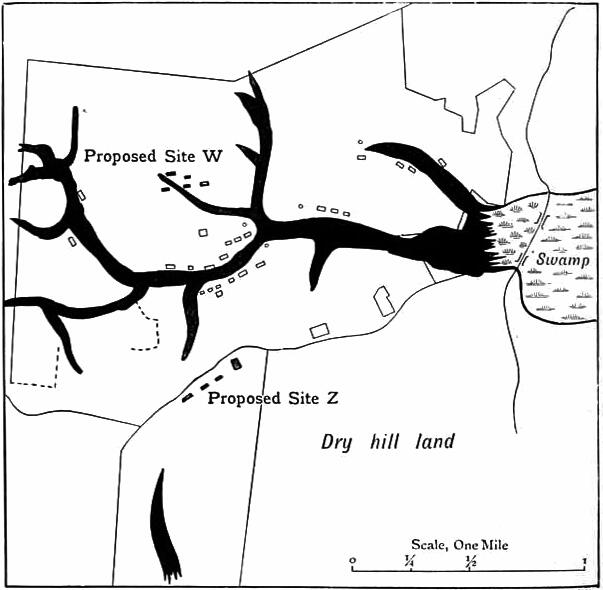

The difficulty on this estate was that swampy land, under different ownership, came within the circle (see Figure 18.3). The coolie lines were well built, and I hesitated at the time to condemn them on account of their site. Now I would not hesitate to do so, and would strongly recommend the alternative site proposed.

| 18.4 |

Estate “JC |

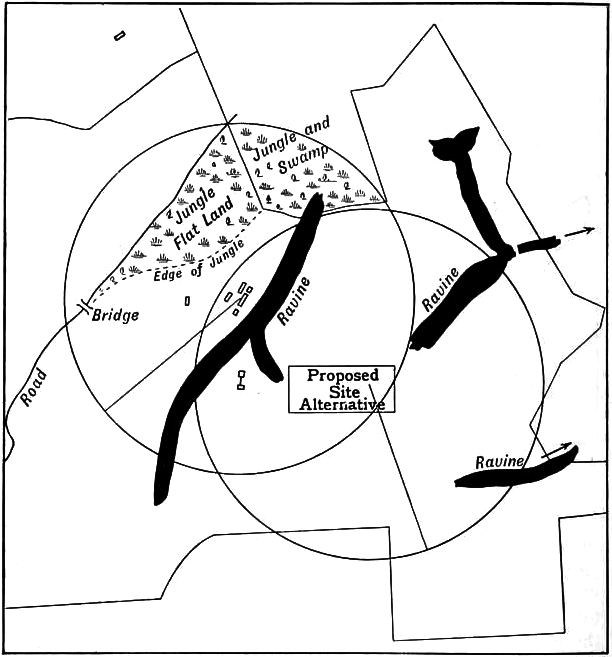

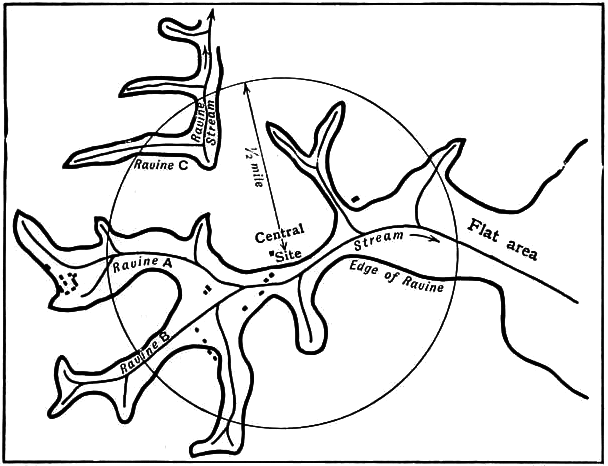

Fig 18.4 shows the buildings of the estate widely scattered. The best course would be to concentrate them about the spot marked “Central Site.” The ravines should be oiled or drained by pipes within the half-mile circle, and outside the circle at the heads of ravines A, B, and C. Alternative sites would be found lower down the main ravine.

| 18.5 |

Estate “SC” |

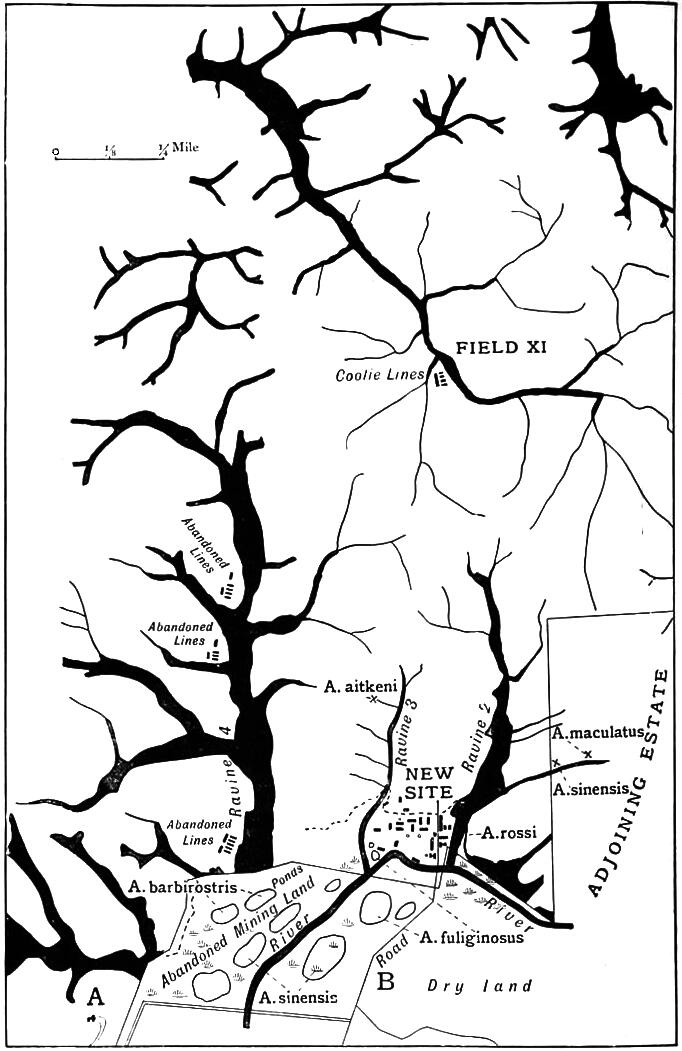

The history of this estate “SC” is of unusual interest. In 1909 I visited it, recommended that the coolie lines in ravine 4 (see Figure 18.5) be abandoned, and selected the site on the bank of the river, which is heavily polluted by mining silt (see Figures 18.6 and 18.7).

The bank of the river is in places swampy, and there are numerous abandoned mining holes filled with water. In the ravine site the mosquito was A. maculatus, the most efficient carrier of malaria in this country; and along the river bank and in the mining holes the mosquitoes were A. barbirostris, A. sinensis, A. fuliginosus var. nivipes, and A. rossi, which are poor carriers, if they carry at all. The removal of the lines led to a great improvement in health; so that in 1913 the average Indian labour force was 857, no fewer than 816 new coolies were introduced, yet the death rate was only 18.6‰. This low rate would be impossible with so large a labour force, if malaria were present to any extent.

The good health continued until August 1914, when malaria broke out severely; and in January 1915 I again visited the estate. At this visit, I was unable to determine the cause of the malaria; but in a subsequent visit in June, A. maculatus was discovered breeding in a branch of ravine 2 coming from an adjoining estate. The ravines 2 and 3 did not contain A. maculatus, and were heavily coated with the felted alga36 referred to in the chapter on oiling (see section 17.5). From 1912, when the adjoining estate was opened, to 1914, the branch of ravine 2 (see Figure 18.5, bottom right) was probably unfit for A. maculatus on account of the silt from the clearings; by 1914 the silt decreased, there was less decomposing vegetation, so the water probably became pure enough for A. maculatus. Oiling this ravine rapidly improved the health, and it has continued good since. Table 18.2 tells its own tale.

| Year | Labour force | death rate |

| 1913 | 857 | 18 |

| 1914 | 561 | 53 |

| 1915 | 427 | 74 |

| 1916 | 422 | 4 |

| 1917 | 512 | 7 |

| 1919 | 614 | 11 |

An examination of forty-one children in 1915 on the river site showed a spleen rate of 43%; in 1920 there were 110 children on the same site, with a spleen rate of 5%.

A few coolies live in a set of lines in Field XI, on a ravine similar to that from which the labour force was removed in 1909. In 1915 there were twenty-two children, with a spleen rate of 100%; in 1920 there were four children, with a spleen rate again of 100%. This shows that the ravines in the centre of the estate still remain intensely malarious; in strong contrast to the site on the swamps next the river.