| 16 |

On the border of the hill land |

On the Coastal Plain and mangrove belt we saw that malaria was controlled by drainage; or by removing the labourers from the vicinity of jungle; or, in some cases, by opening the jungle so as to push it away from the labourers’ houses. On the hill land, the policy has been to concentrate the labourers at the centre of sanitary circles within which all mosquito breeding places are destroyed.

A number of estates border on the hills; part of the land is flat, and part hilly. In controlling malaria on these, sometimes one method, sometimes another, and sometimes a combination of methods have been employed. In this chapter I propose to give some examples of the problem as it presented itself, and describe what was done in each case.

| 16.1 |

North Hummock Estate |

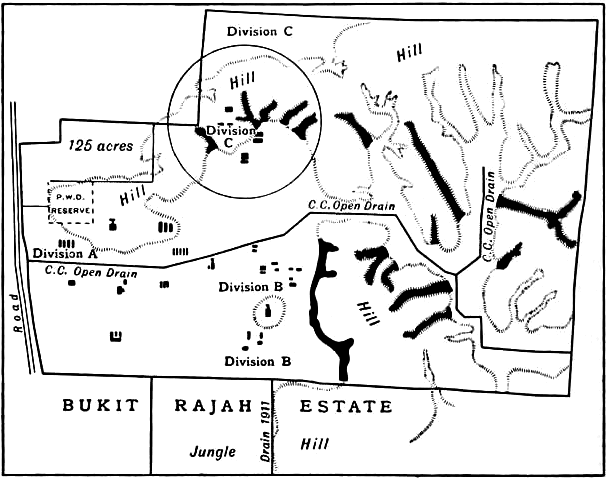

This estate is situated on the border land about four miles north of the town of Klang. From the first it was intensely malarious, Europeans and Indians alike suffering. It consists of three divisions—as will be seen from the plan (Figure 16.1); each was dealt with differently.

| 16.1.1 |

Division A |

The lines on this division were situated on flat land at the end of a spur of the hill. A. umbrosus was abundant, and came from the unopened swampy jungle marked 125 acres, part belonging to the estate, and part to a reserve of the Public Works Department of Government.

In 1911 permission was obtained from Government to open its portion (37 acres) of the land; at the same time the estate, on my recommendation, opened the 125 acres which it owned. The result was an immediate improvement in health, as the spleen rates in Table 16.1 show. The large increase in the child population and decrease in the spleen rate makes comment unnecessary.

| Division | Year | No. of children examined | Spleen rates (%) |

| A | 1905 | 5 | 40 |

| 1906 | 5 | 80 | |

| 1909 (Dec.) | 32 | 59 | |

| 1911 (Nov.) | 54 | 35 | |

| 1913 (Jan.) | 32 | 9 | |

| 1914 (Feb.) | 90 | 3 | |

| 1914 (Nov.) | 87 | 2 | |

| 1916 (Nov.) | 97 | 4 | |

| 1917 (Feb.) | 74 | 4 | |

| 1918 (Jan.) | 109 | 1 | |

| 1918 (Jun.) | 103 | 0.9 | |

| 1920 (Jan.) | 110 | 0 | |

| B | 1911 (Nov.) | 34 | 50 |

| 1913 (Jan.) | 72 | 5 | |

| 1914 (Feb.) | 70 | 2 | |

| 1914 (Nov.) | 122 | 5 | |

| 1916 (Feb.) | 90 | 3 | |

| 1917 | 112 | 5 | |

| 1918 (Jan.) | 128 | 6 | |

| 1920 (Jan.) | 128 | 2 | |

| C | 1911 | 12 | 91 |

| 1913 | 14 | 14 | |

| 1914 | 77 | 16 | |

| 1914 | 55 | 16 | |

| 1916 | 42 | 21 | |

| 1917 | 44 | 15 | |

| 1918 | 72 | 8 | |

| 1919 | 62 | 9 | |

| 1920 | 55 | 10 |

| 16.1.2 |

Division B |

Here the malaria came from swampy jungle about twenty chains away. The problem was complicated; for that jungle belonged to another estate, and there was no intention of opening it.

The problem was solved in a curious way. In connection with the water-supply of the adjoining estate, I had suggested a large catchment drain at the foot of the hill marked Bukit Rajah on the plan; this was made, and other drains in the jungle were also dry. The result was to dry the jungle so that it no longer provided a breeding place for A. umbrosus. At the same time some breeding places of A. maculatus in the hill near to the lines were drained by subsoil drains. The spleen rate at once fell.

In both 1917 and 1918 two of the children with enlarged spleens arrived ill, the result of malaria contracted in India. In 1920 two of the three children with enlarged spleen had recently suffered from malaria. They had been several years on the estate, where presumably they had contracted it. The third was a recent arrival from a malarious estate.

| 16.1.3 |

Division C |

This division is of special interest. The lines were situated on a portion of the spur of hill land that terminates at the lines of Division A. The hills are intersected by a number of quite short ravines, each only about a couple of hundred yards long. They debouch onto the flat land where the soil was somewhat peaty. The ravines, except one, swarmed with A. maculatus, which were controlled by subsoil drainage of the ravine streams.

As A. maculatus is never found in peaty water, it was unnecessary to pipe-drain a complete circle here, so the pipes ended as soon as they reached the peaty water. This knowledge of the habits of A. maculatus thus saved the estate much unnecessary expense; and the very small lengths of ravines to be drained made the cost of the control of malaria only a nominal sum—some $1500.

The malaria had been so intense that even Banjarese, a race of Malayans, who are usually immune to malaria, could not live on the division, and the Tamils were decimated. The spleen rates listed in Table 16.1 shows the improvement.

In 1920 three of the six children with enlarged spleen gave history of fever previous to coming to the estate, and another new arrival had a greatly enlarged spleen. Here, as on other healthy estates, there are children who have imported their spleens and malaria. The true spleen rate, therefore, is under 4. For the whole estate the death rate of 1919 was 9‰.

| 16.2 |

The value of subsoil drainage to agriculture |

Subsoil drainage proved of advantage to the estate from a point of view other than health; it has been of value in maintaining an efficient drainage system on the flat land. The attached letter from the manager gives an account of what the anti-malarial work has meant to the estate:

North Hummock (Selangor) Rubber Co. Ltd.,

Klang, 7th November 1919.

Dear Dr. Watson,

With reference to your request for an account of the work done on North Hummock Estate to improve the health, and particularly that done to control malaria, I have much pleasure in sending you these notes.

I joined this estate in 1910, and have been on it since that date, first as an assistant, and later as manager.33 When I first came, the estate was malarious, and all who lived in the bungalow on ‘A’ Division suffered severely from malaria. After the opening-up of the swampy jungle in that division, the malaria soon disappeared.

Division ‘C’, in which the coolie lines are situated on small hills intersected by small ravines, was intensely malarious, so much so that a satisfactory labour force could not be got together there. The subsoil drainage soon improved the health, and this is now as healthy as any division on the estate. Indeed, there is at the present moment a larger labour force than is actually required.

On ‘B’ division subsoil drainage was also laid down in certain ravines adjacent to the lines, and along the foot of the hills. This was done not only to improve health, but because it was an effective way of preventing silt from reaching the open drainage system. We had first noticed this advantage on ‘C’ division, and by its employment on ’B’ division it was possible to prevent the ‘CC’ drain (the main drain of the estate) from becoming silted up. Many acres of rubber were thus saved from certain destruction, and some acres were reclaimed. The system of subsoil drainage has been systematically extended throughout the estate ravines, quite apart from the health question, far beyond half a mile from any habitation and solely as an agricultural measure.

The cost of this subsoil drainage has been small. It has been carried out entirely by the estate staff without outside or engineering assistance. In very wet weather the ravines are kept under supervision, as occasionally small places scour, but many of the ravines have not cost a cent in repair, since the pipes were laid down in 1912 and 1913. It has been this long and satisfactory experience of it which has made it the deliberate policy of the estate to deal with ravines by means of subsoil drainage.

The experience of the last few years has shown the advisability of deepening the drainage generally throughout the flat portion of the estate. This has been done, and led to an increased output of rubber. But it would not have been possible to maintain the increased depth in the drains, had the silt from the hills not been held back. Today, in spite of a reduction in the amount of their normal food supply, and in spite of difficulty of recruiting, the estate has become so popular with labour that there are now some 1600 men, women, and children on it. As the figures show, the health is excellent, and the death rate promises to be below 10‰ for the year.

To sum up, by clearing and draining jungle, by deepening the open drains in the flat land, by subsoil drainage of ravine streams, what was once an intensely malarious estate with an inadequate labour force is now one of the healthiest in the country, and possesses a large and contented labour force.

Finally, the measures taken to improve health have no less proved of the greatest value from an agricultural and financial point of view.

Yours sincerely, T. Donaldson.

| 16.3 |

Bukit Rajah Estate |

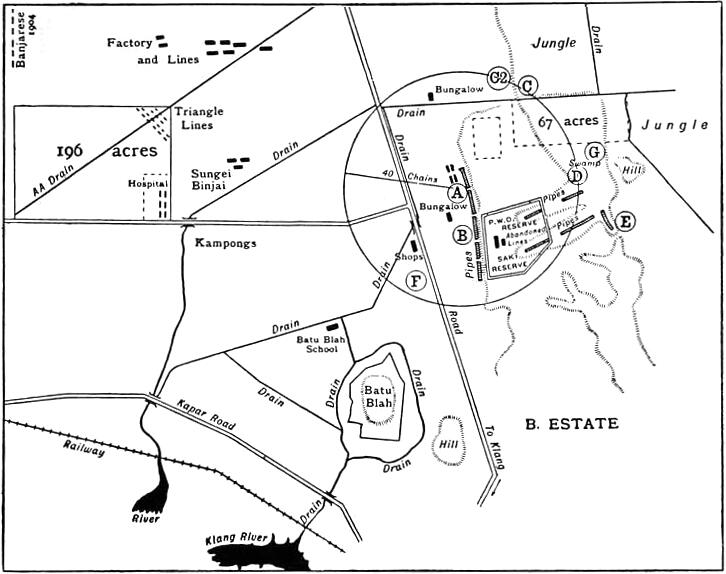

I have known this estate as malarious since I came to Klang; for, although it had been opened up for a year or two before my arrival, it was not a large estate, and coolies were living close to jungle. Today it is a large estate (see Figure 16.2), with some 4000 acres opened, part of it hilly and part flat. The coolies are housed on different parts of the estate; they are now almost free from malaria. The following gives a brief account of what was done to make them so.

| 16.3.1 |

Triangle lines |

These were close to the corner of a block of jungle marked “196 acres”, through which runs the large drain “AA.” In 1911 this jungle was opened and planted on my recommendation; the spleen rates show the improvement (see Table 16.2).

| 16.3.2 |

Tamils at Sungei Binjai |

The fever in these lines came from the jungle of the 196 acres, and from what are now small native holdings on the south boundary. Again, the spleen rates show the improvement (see Table 16.2). Of the four children with enlarged spleen in 1914, three came from a malarious estate. In 1917 the children were examined along with those in the triangle lines.

| Division | Year | No. examined | Spleen rates (%) | Parasite rates (%) |

| Banjarese | 1904 | 24 | 50 | 62 |

| 1905 | 15 | 60 | 60 | |

| 1906 | 15 | 13 | ||

| 1910 | 35 | 23 | ||

| Batu Blah school | 1909 | 53 | 45 | |

| 1914 | 60 | 45 | ||

| 1916 | 62 | 30 | ||

| 1917 | 67 | 37 | ||

| 1918 | 54 | 20 | ||

| 1919 | 53 | 5 | ||

| Boon Hean (Site B) | 1909 | 17 | 93 | |

| Boon Hean (whole) | 1909 | 65 | 42 | |

| 1914 | 63 | 14 | ||

| 1915 | 49 | 22 | ||

| 1917 | 62 | 6 | ||

| Factory | 1904 | 42 | 19 | 41 |

| 1905 | 34 | 32 | 32 | |

| 1906 | 7 | 14 | ||

| 1909 | 72 | 4 | ||

| 1910 | 51 | 6 | ||

| 1914 | 11 | 0 | ||

| 1917a | 11 | 18 | ||

| 1917b | 19 | 36c | ||

| Sungei Binjai | 1906 | 8 | 37 | |

| 1909 | 9 | 22 | ||

| 1914 | 48 | 8 | ||

| Sungei Rasak | 1910 | 12 | 15 | |

| 1914 | 74 | 14 | ||

| 1915 | 34 | 8 | ||

| 1917 | 46 | 4 | ||

| Triangle lines | 1906 | 7 | 14 | |

| 1909 | 22 | 18 | ||

| 1910 | 42 | 7 | ||

| 1914 | 54 | 2 | ||

| 1917d | 102 | 4 |

- a

- Malaysians

- b

- Tamils

- c

- True rate = 0

- d

- According to the text, the number for 1917 includes the children from Sungei Binjai for the same year (M.P.)

| 16.3.3 |

Banjarese |

At one time a number of these people lived along the edge of the jungle that is now Shelford Estate. They suffered greatly from malaria. They subsequently removed to native holdings on the road.

| 16.3.4 |

Tamils at the factory |

In 1904 the nearest jungle according to the estate plan was 40 chains away; nevertheless the parasite and spleen rates were high. Later, they dropped to normal. In 1917 the rise is owing to the recruiting of labour from an estate known to be intensely malarious. It is, however, easy to make the necessary correction; and I give it as an example of the ease with which the correction can be made, and of how little one is liable to be misled by using spleen rates even on rubber estates where the population moves so freely. Of the seven Tamils with enlarged spleen in 1917 (cf. Table 16.2), all had come from a malarious estate; and the same is true of the Malayalans.

| 16.3.5 |

Blackwater fever |

A case of this occurred in a bungalow in field 139 acres, before the jungle on the opposite side of the road belonging to North Hummock Estate was opened.

| 16.3.6 |

Boon Hean Division |

In the previous places the problem was simply that of removing and draining jungle on flat land. The Division of which I now write was a pestilential spot, full of difficulties for the sanitarian. The coolie lines were scattered, and mostly close to jungle. Part of the land was hilly, and A. maculatus, the dangerous hill-stream mosquito, existed on it. Another difficulty was that 57 acres belonged to Government—part being a quarry reserve which was of value for road upkeep, and which Government was strongly opposed to selling. The Government land was, however, intensely malarious. About 1902 I chose the top of the hill as a site for coolie lines for the Public Works Department, going on the teaching that in a malarious country a hill was the best site, and that elevation, however slight, was preferable to the heavy clay of flat land: “As high ground as possible is the golden rule for a camp. Against the vertical uprising of malaria, elevation, however small, affords some protection.”

The lines were built on the site I selected, but the coolies promptly died of malaria; and until the land was handed over to the estate they remained uninhabited and uninhabitable. On one occasion a man attempted to occupy the overseer’s bungalow; but he, too, had to leave.

To show how intensely malarious the whole area was in 1909, I will give the spleen rates of the various lines. At B, 14 out of 17 or 82% had enlarged spleen. At F, which is farther from the jungle, there were 9 out of 22 or 40% with spleen. At C, the lines were within 20 yards of the jungle, and the spleen rate was 10 out of 11 or 90%; while at C2, which is 200 yards from the jungle, it was 8/15 or 53%. In 1912 coolies were put into the lines D, E, and G, but the health was so bad they had to be moved. I have no figures of the spleen rates.

In order to give the estate a healthy labour force, I decided it would be best to “scrap” almost all the existing lines and sites, and to create a new healthy site somewhere in the area. Accordingly, I made the following recommendations, which were adopted, with the happiest results:

- Site A was selected as the future headquarters of the Division—but not because it was healthy; for it was only a few yards from the Government reserve and site B where the spleen rate was 82%. It was chosen because it was possible to abolish all breeding places within half a mile. Site F would be protected by the same measures.

- Sites C, C2, D, E, and G were abandoned, because they were close to jungle. To make them healthy, it would have been necessary to open up extensive areas of jungle, and probably lay down considerable subsoil drainage; this was undesirable, since the jungle and hills formed the catchment area of the water supply.

- Part of the jungle marked 67 acres was drained and planted with rubber. The Government reserve was exchanged for a piece of land suitable for a rifle range. The reserve was cleared of jungle, and planted up; while the ravines were drained by subsoil pipes.

After these measures were carried out, the health improved, as the spleen rates in Table 16.2 show. In 1917, there were four children with enlarged spleen; three of these belonged to one family which had recently come from a malarious estate; the fourth child, with a spleen just palpable, came from an estate on which malaria had recently existed. There is now a large healthy labour force on a site which formerly was uninhabitable.

| 16.3.7 |

Sungei Rasak division |

This division has always been healthy, for the lines have never been less than 30 chains from jungle, and I had advised the manager not to put new lines among the ravines; they are situated at the end of a spur of the hills. In 1917, one of the two children with enlarged spleen had been on the estate only a week, showing it had brought the enlarged spleen to the estate.

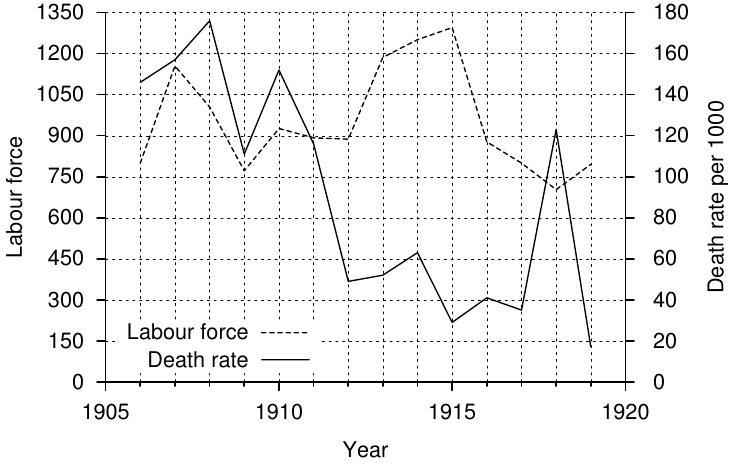

| Year | Labour force | Death rate (‰) |

| 1906 | 950 | 43 |

| 1907 | 1150 | 45 |

| 1908 | 1125 | 63 |

| 1909 | 993 | 29 |

| 1910 | 1144 | 33 |

| 1911 | 1143 | 39 |

| 1912 | 1146 | 34 |

| 1913 | 1254 | 39 |

| 1914 | 1146 | 14 |

| 1915 | 1157 | 19 |

| 1916 | 1215 | 7 |

| 1917 | 1269 | 14 |

| 1918a | 1374 | 32 |

| 1919 | 1459 | 10 |

- a

- Influenza

| 16.3.8 |

Death rate of estate |

The various measures taken to improve health, chiefly the anti-malarial work, have resulted in a lowering of the death rate (Table 16.3). The labour forces and death rates are taken from the official report of the Labour Department, except for 1919, which are based on the average monthly population. Further comment is hardly necessary.

| 16.3.9 |

Batu Blah drainage |

Close to the Boon Hean Division of Bukit Rajah Estate are many kampongs or native holdings. Until 1916, the drainage of the kampongs around Batu Blah Hill was defective. A. umbrosus was to be found in many drains and in wells around the hill. Consequently, malaria was prevalent. Two European houses and several of the better classes of native houses, built here from the spread of the town, were abandoned on account of their unhealthiness.

In 1914, I represented this to Government; in 1916, about $3000 were spent on an open drainage system. The spleen rate of Batu Blah Malay School has steadily fallen since (see Table 16.2). In 1919, two of the three children with enlarged spleens were old residents; the third lived 11/2 miles away.

The abandoned houses have been reoccupied. There is now no complaint from the natives; at first they said they could not get sufficient water; their wells were dried up or closed, and they had to go some distance to the pipe supply. Now they are reconciled, as the improved drainage has given them larger crops—mainly of rubber.

| 16.4 |

Midlands Estate |

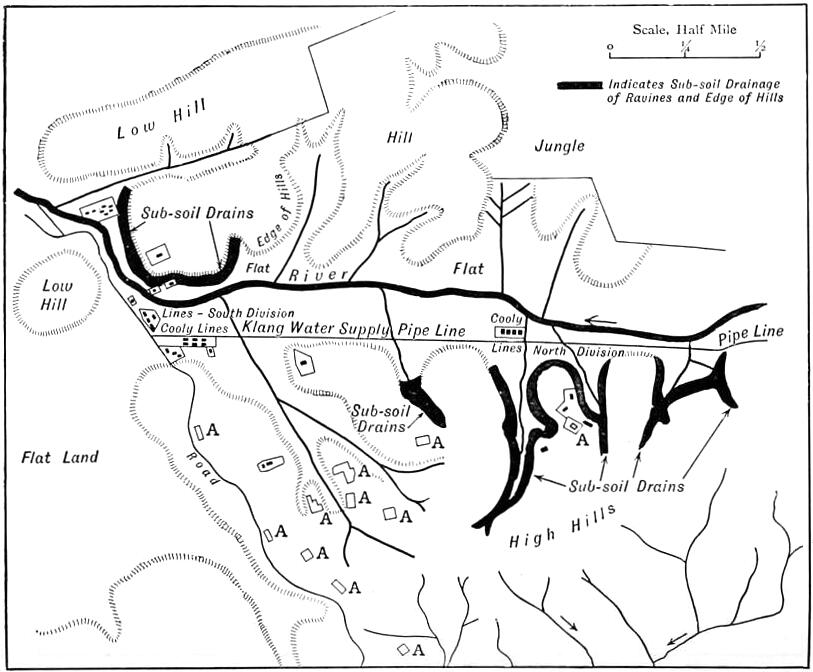

When first opened in 1906 this estate was intensely malarious, because the first clearings were on the hills, and the labour force was housed on ravines teeming with A. maculatus.

| Division | Year | No. of children examined | Spleen rates (%) |

| North | 1909/10 | 21 | 76 |

| 1914 | 22 | 63 | |

| 1918 | 20 | 20 | |

| 1920 | 29 | 6 | |

| South | 1906 | 61 | 65 |

| 1907 | 43 | 83 | |

| 1909/10 | 153 | 45 | |

| 1914 | 78 | 21 | |

| 1917 | 48 | 6 | |

| 1918 | 115 | 2 | |

| 1920 | 143 | 2 |

Quinine was given, and the coolies were fed in the morning before going to work, with a certain improvement in health, but not sufficient to enable a healthy Indian labour force to be established.

When more of the estate had been opened, sites on the flat land were available, and the hill land sites were abandoned. The estate is now worked in two divisions. The North Division coolie lines were moved 25 chains or 1/4 mile, and the South Division lines 50 chains. In neither case was it possible to move the lines 1/2 mile from all hills, so additional measures were taken to control the breeding places of A. maculatus within the sanitary circle, namely subsoil drainage and oiling.

There were difficulties with the subsoil drainage in certain places owing to the impervious clay soil, and much of this drainage was pulled up. It is used now as subsidiary to oiling in short lengths round the hills. Open drains round the hills are also oiled for 1 chain from the foot of the hills; special attention is paid to seepage areas. It has not been found necessary to oil the drains in the flat bottom of the valleys, partly because the main drain contains peaty water, which never contains A. maculatus, and partly because the oiling of the hill-foot drains pollutes the other drains on the flat.

| 16.4.1 |

South or Old division |

The removal of the lines was commenced in July 1913 and was completed by February 1914. The effect of this and the other measures is shown in the fall of the spleen rate (Table 16.4).

In 1920 there were three children with enlarged spleens; two of those were a brother and sister locally recruited three months before; the other was a child many years on the estate, whose spleen was just palpable. The true spleen rate is, therefore, under 1% and is in keeping with the low death rate (see Table 16.5).

In December 1914 in a report I made this remark:

But marked as this improvement is, an analysis of the figures gives curious and interesting independent evidence of the improvement which is taking place. In 1909-10, in the lines situated on the Government Road, and subsequently abandoned, 21 out of the 22 children had enlarged spleen; the spleen rate of the children who had been over six months on the estate was 81%; and out of the total 153 children on this division there were only 4 infants.

Now I find that among the 57 children who have been longest on the new site (since July 1913) only 8 or 14% have enlarged spleen, not a single one (except 1 in hospital) is ill, and there are 9 fat, healthy infants. On the other hand, of 21 children removed to the new site in February 1914 still 9 or 42% have enlarged spleen; but even here only 1 is ill, and there are 3 healthy infants.

This note is interesting, as giving a glimpse of spleen rates during a transition stage from high to low.

| 16.4.2 |

North division |

The same policy was advised for the North Division of the estate. On 3rd August 1910 I wrote to the manager:

Sites in proximity to the hills which pretty much follow the cart road, as shown on the plan, are to be regarded as unhealthy. It is, therefore, desirable to put the lines and bungalow as far as possible from them. I, therefore, advise that the new buildings be put close to the pipe line. This will put them close to jungle, which is also unhealthy, but it might be possible to make the clearings in the near future along the pipe line, thereby improving the health of the new buildings.

The buildings were put on the road close to the hills, and proved unhealthy. Between January and October 1914 some ravines were pipe-drained and others oiled, which improved the health. In 1915, 1917, and 1918 various blocks of the flat land beyond the pipe line were opened up, pushing the jungle some 40 chains from the pipe line, and making it possible to remove the labour force to the site suggested in 1910; and the whole labour force was removed early in 1918, with satisfactory results, as the figures will show. Not until 1919 was the jungle taken a full half-mile from the lines.

The plan (Figure 16.3), showing the abandoned sites, gives a better idea of the policy adopted than anything I can write; so I refer the reader to the study of it.

The drainage and oiling were not in force until towards the end of 1914, and so at that date the spleen rate was still high. The labour force was not removed from the hills until March and April of 1918. Hence the spleen rate of this division fell at a later period than on the South Division (see Table 16.4).

In 1920 there were two children with enlarged spleen; one, born on the estate, had a spleen barely palpable; the other, a local recruit, had been about three months on the estate.

| Year | Average population | Death rate |

| 1907 | 750 | 73 |

| 1908 | 1256 | 165 |

| 1909 | 1369 | 56 |

| 1910 | 1114 | 110 |

| 1911 | 940 | 189 |

| 1912 | 861 | 82 |

| 1913 | 824 | 78 |

| 1914 | 713 | 42 |

| 1915 | 528 | 15 |

| 1916 | 547 | 14 |

| 1917 | 597 | 11 |

| 1918a | 622 | 48 |

| 1919 | 616 | 8 |

- a

- Influenza

| 16.4.3 |

Death Rates |

With the falling spleen rates the death rates came down, as Table 16.5 shows. In the years 1909 and 1910 large numbers of Telegu coolies were recruited. It was not until the end of 1911, when Mr. Harrison became manager, that special measures against A. maculatus were commenced. In the first four months of 1920 only one death has occurred; it was from epilepsy.

The approximate cost of oiling each area of a half-mile radius is $400 per month.34

This estate is a brilliant example of how intense malaria can be overcome by removal of buildings to the best sites, coupled with subsoil drainage and oiling to breeding places within the new sanitary area. Quinine is not given to any except the sick.

This work has been carried out entirely by the manager, Mr. C. R. Harrison, and reflects the highest credit on him.

| 16.5 |

Damansara Estate |

This estate is situated on the border of the hill and flat land. The measures taken to improve health have been giving quinine, opening swampy jungle, removal of labour from hill to flat land, and oiling. The original Damansara Estate acquired Telok Batu Estate in 1906, and Labuan Padang Estate in 1907. From a medical point of view, I regard the group of estates as composed of five divisions; as the coolie lines are situated in five groups at some distance apart and under different malarial influences.

| Division | Year | No. examined | Spleen rates (%) | Parasite rates (%) |

| A | 1904 | 9 | 11 | 22 |

| 1909 | 9 | 22 | ||

| 1911 | 10 | 30 | ||

| 1913 | 13 | 23 | ||

| 1914 | 15 | 13 | ||

| 1915 | 20 | 5 | ||

| 1920 | 33 | 3 | ||

| B | 1904 | 32 | 15 | 40 |

| 1909 | 31 | 51 | ||

| 1911 | 27 | 14 | ||

| 1913 | 22 | 27 | ||

| 1914 | 39 | 20 | ||

| 1915 | 55 | 12 | ||

| 1920 | 39 | 0 | ||

| C | 1909 | 9 | 100 | |

| 1911a | 1 | 100 | ||

| 1913 | 9 | 22 | ||

| 1914 | 22 | 27 | ||

| 1915 | 18 | 16 | ||

| 1920 | 27 | 7 | ||

| D | 1914 | 12 | 75 | 100 |

| 1905b | 17 | 11 | ||

| 1906 | 18 | 94 | ||

| 1909d | 12 | 100 | ||

| 1909d | 30 | 76 | ||

| 1911 | 24 | 66 | ||

| 1913 | 39 | 76 | ||

| 1914 | 44 | 50 | ||

| 1915 | 33 | 66 | ||

| 1920 | 44 | 9 | ||

| E | 1906 | 26 | 76 | |

| 1909 | 13 | 100 | ||

| 1911 | 6 | 66 | ||

| 1913 | 11 | 81 | ||

| 1914 | 12 | 83 | ||

| 1915 | 19 | 84 | ||

| 1920e | 33 | 6 |

- a

- Lines removed to new site in 1911

- b

- Quinine given carefully

- c

- Old site

- d

- New site

- e

- True rate: 8

Table 16.6 lists the examination results for children on this estate. Some spleen and parasite rates for 1905 and 1906 have been omitted, as the records of divisions “A” and “B” had unfortunately not been kept separate.

| 16.5.1 |

Division “A” |

This division is situated on the river. To improve the health, quinine was given with the greatest care by Mr. H. F. Browell from 1904. In 1910 about six acres of secondary jungle and undergrowth was removed. In 1912 and 1913, 150 acres of land belonging to another estate on the opposite side of the river was opened. Some jungle still remains within 40 chains. The figures in Table 16.6 show the result.

| 16.5.2 |

Division “B” |

On my recommendation, in 1910, jungle to the extent of 108 acres of flat land was opened. Later on, still more flat jungle belonging to an adjoining estate was opened, and hill-land ravines extensively oiled.

| 16.5.3 |

Division “C” |

The lines were situated on a low spur of the hills, with streams breeding A. maculatus on each side. In 1910, I recommended that the lines be removed to a site on the flat, then under swampy jungle. Part of this jungle belonged to another owner, but it was acquired by the estate, and the whole block comprising 87 acres was drained and planted. Division “C” was removed to it, and on it was built the estate hospital.

In 1920, one of the two children with enlarged spleen was a local recruit from an unhealthy locality. The true spleen rate was 3-5%.

| 16.5.4 |

Division “D” |

Formerly an intensely malarious spot. Two streams breeding A. maculatus were on the sides; in front was a mass of swampy, flat-land jungle. This is the estate to which I refer in Chapter 11 on the effects of malaria in children:

Among the children malaria is no less severe. On one occasion I was asked by a manager to advise him what should be done for the children, as fifteen had died in the previous two months out of a total of thirty-three. He told me a native clerk was giving them quinine daily. I examined the blood of the remaining eighteen, and easily found parasites in seventeen.

The manager then gave personal attention to the quinine administration of the children, and there were only two deaths in the next three months, these being children who were seriously ill before he took it in hand. The effect of this terrible death rate on the coolies was such, that even although they were living in good lines built less than three months before, and on land opened for ten years, they declared the lines were haunted. The lines had to be pulled down and rebuilt elsewhere.

The new site was on the river about 300 yards from the old one. The health improved when the flat land across the river was planted, and a ravine, part of which is probably not so suitable as it was for A. maculatus, on account of shade, was oiled for a time. (See Section 25.6 on the mosquitoes of ravines.)

| 16.5.5 |

Division “E” |

The lines are situated on the end of a spur of the hills, on one side of which is a ravine, while in front is flat land. The most important ravine has been oiled intermittently since 1914, and regularly since 1918. The ravines farther off are under the shade of heavy rubber and small undergrowth, and so are less suitable for A. maculatus than they were previously.

In 1905, when quinine was being given with great care, the parasite rate of seventeen children was 23.5%. In 1906, parasites were found in twenty-five out of twenty-six children; the single child without parasites had suffered from “fever” four days before, and was on quinine; its spleen was enlarged.

In 1920, of the two children with enlarged spleen, one was a local recruit only six weeks on the estate; the other child was born on the estate. All the children looked well.

| 16.5.6 |

The death rates |

With spleen rates so high, one would expect to find high death rates, if many new coolies were employed; and this was so. The estate originally was not uniformly malarious, as will have been noticed from the spleen rates; but the two divisions last mentioned had at one time an appalling mortality not only among the children but among the adults. For example, in 1906, on Division “E” there were 116 coolies on the 1st January; 170 were recruited from India. Of the 286, 26 deserted, and 60 died; the death rate, worked out on the quarterly labour force, was 300‰.

In 1907 the death rate of the 275 coolies on “E” Division was 178‰; of 275 coolies on “D” Division it was 200‰; and of 700 on Divisions “A” and “B” it was 138‰. These are examples of what malaria can do; and they occurred despite the most careful administration of quinine. On Division “E” the names of the occupants of each room were put on a special check roll, and each person was accounted for and given quinine daily, with extra doses of quinine solution when ill. Euquinine was given to the children.

The European staff suffered no less than the Asiatic, and the manager had to be invalided in 1907. Yet this intense malaria has been slowly overcome, and health has steadily improved since 1910, when radical methods were adopted on Divisions “A” and “B,” namely, the opening of swampy jungle and removal of coolie lines. Later, oiling, more or less efficiently carried out on the other Divisions, the opening of some jungle, and probably the heavy and close shade of rubber trees and ferns now growing in some of the ravines, have contributed to reduce the number of stream-breeding mosquitoes.

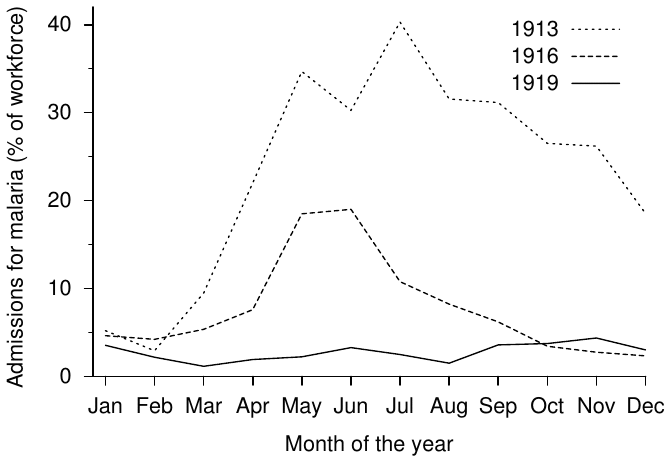

The death rates (Table 16.7; Figure 16.5) show the nature of the change. Still further improvement may be anticipated with confidence.

| Year | Labour force | Death rate (‰) |

| 1906 | 800 | 146 |

| 1907 | 1155 | 157 |

| 1908 | 1005 | 176 |

| 1909 | 772 | 111 |

| 1910 | 926 | 152 |

| 1911 | 892 | 116 |

| 1912 | 887 | 49 |

| 1913 | 1186 | 52 |

| 1914 | 1251 | 63 |

| 1915 | 1295 | 29 |

| 1916 | 877 | 41 |

| 1917 | 800 | 35 |

| 1918a | 703 | 123 |

| 1919 | 795 | 17 |

- a

- Influenza

| 16.6 |

Jugra Hill |

The estates in the district of Kuala Langat, whose history is given in Chapter 8, are on flat land, and the malaria from which they suffered at one time was carried by A. umbrosus. But in the district rises Jugra Hill, a mass of granite 915 feet high, isolated from all other hills by some 15 to 20 miles of flat land. It is not uninteresting, as Dr. Leicester [7] remarks, that the mosquitoes of the hill are not those of the surrounding flat land, but of hill land. And among the hill mosquitoes is A. maculatus, the stream breeder. As a result of its presence, all around Jugra Hill has been extremely malarious, while only a short distance from it people have enjoyed good health.

What amounts to an experiment took place a few years ago, when a set of lines belonging to the Public Works Department was removed from the base of the hill to a spot a mile from it. The result was an immediate and marked improvement in the health of the coolies, which has ever since been maintained. The condition of the coolies in 1901 and 1902 can be seen from the following extract from a report dated 15th January 1902, made by me to the Government on the prevalence of malaria in Jugra.

- 4.… But I would like to draw attention to some observations made at the P.W.D. coolie lines at Permatim Pasir which show that the malaria is not confined merely to the town, but extends round the foot of the hill, and which also explains the absolute refusal of many of the coolies to remain after the term of their agreement had expired, although they were willing to work at Klang.

- 5.On 5th February 1901,

- out of nine persons in the lines one alone was healthy;

- two men and one child had malarial fever;

- two children, two men and one woman had enlarged spleens, the result of repeated attacks of malaria.

I was informed about fifteen coolies were living there at the time.

- 6.On 10th July 1901, I found of these P.W.D. coolies:

- In the lines: two women, one man and three children with malarial fever.

- In the hospital: seven with fever, and three with enlarged spleens and ulcers.

At this time there were about thirty-four persons living in the lines.

- 7.On 7th January 1902, there were eleven children under ten years present at my visit. All without exception had enlarged spleen. Two women had fever.

The overseer volunteered the statement that fifteen children had died within the past six months, which is not improbable, as malaria often affects children severely.

As the result of these representations the lines were removed in 1903 from the immediate foot of the hill, and, taking no risk, I advised they should be put a mile from the hill.

The result has been successful in the highest degree. From 1903 onwards I have often gone to the lines, and I have never once found a coolie in them suffering from fever, although doubtless a coolie may occasionally do so.

On 18th January 1910, I examined fourteen children in the lines. Two of them had splenic enlargement, and the overseer told me both had come to the place about a year before from other P.W.D. lines, and that they had not suffered from malaria since their arrival.

The overseer said he had been two years in the lines, and had not suffered from fever. No children had died since he had been in charge; the only death had been that of a coolie who was ill when he arrived from India, and had died shortly after his arrival. No adult or child had fever on the day of my examination.

That no improvement has taken place in the health condition at the foot of the hill, is to be seen from an examination of thirty-five Malay children in the Permatim Pasir School made on 16th May 1909. Of the thirty-five, eleven, or 35% had enlargement of the spleen. This is in marked contrast to the P.W.D. coolies only a mile from the hill, and from the freedom from malaria on the Estates “KK” and “LL,” distant 11/2 and 2 miles, respectively.

The town of Jugra, situated at the foot of the hill, is the official headquarters of the district; but it has been so persistently malarious since 1896 that in 1917 the Government decided to remove it to a site on flat land about 5 or 6 miles from the hill. The new buildings are now in course of erection. The new site is close to Estate “TT,” so it should be healthy.

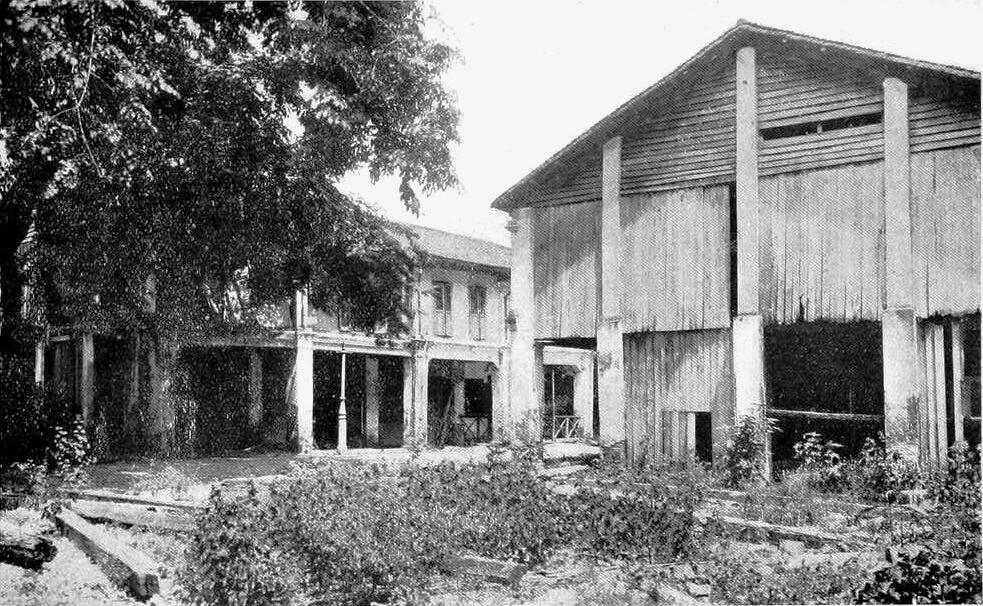

Practically half of the shop houses of the town have been abandoned or pulled down; more than half of one side of the street has disappeared. The place forms a picture of desolation to which the camera (Figure 16.6) fails entirely to do justice.

In passing, I may mention that the story of the malaria of Jugra given in Volume I of the Studies from the Institute for Medical Research is entirely wrong. The coolies came to Jugra to work the quarries in 1898, not in 1896 as stated; and malaria had been rapidly increasing for two years before their arrival, as the table printed in the study shows. The coolies did not introduce the disease; they were its victims.

| 16.7 |

Karimon Island |

I will now give an instance where the hill land bordered not on flat land, but on the sea.

At Malarco, on the Great Karimon, one of the Dutch islands of the Archipelago, some 30 miles from Singapore, a company had started a large factory for the treatment of jelutong, a “wild rubber” found in the Malay Archipelago and Peninsula. A first-class factory, with electricity as its motive power, had been erected. A model village had been built, and a pure water supply had been brought in from a reservoir 3 miles away. The village was on a reclamation, with deep water immediately beyond; and the latrines were over the sea. Everything that could be thought of to improve health had been done, including the clearing of jungle and undergrowth for some acres round the site. Despite everything, the people were “much troubled with a virulent form of malaria.” Mr. Galbraith, the General Manager in the East, invited me to visit the island, and advise on what should be done to improve health.

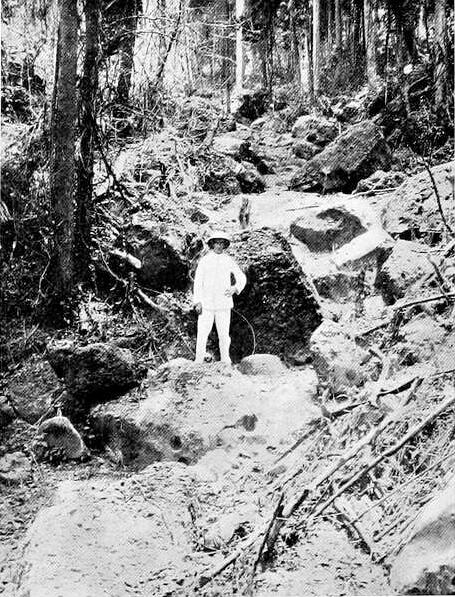

This I did on 22nd July 1912. The factory and village were on the end of the island which rises steeply from the sea, as is seen from the photograph (Figure 16.7). In front of this is a small island, which thus forms a breakwater to Malarco. Through the Strait a steady breeze blew both night and day during my visit. For the general sanitary conditions, I had nothing but praise. “The buildings in which the coolies are housed are of excellent design, of good construction, maintained in good order, and well laid out,” was my note on the housing; and other sanitary arrangements were equally well carried out. There was a coolie population of between 800 and 900.

| 16.7.1 |

Evidence of malaria |

There being practically no native child population, no spleen rate could be obtained. The death rate was also valueless. When ill, many of the Chinese left for Singapore, where indeed a number died in the hospitals; eight are reported to have died in Singapore hospital in January 1912; but many Chinese refuse European treatment, go to friends, and die unknown to the manager of the place they come from. The hospital statistics showed that in 1911 there had been 811 admissions, of which 72% were for malaria; from 1st January to 20th July 1912, there had been 389 admissions, malaria being 61% of them.

The Europeans were suffering no less than the Asiatics, and a number had resigned. Of a total of thirteen former residents, I was informed that eleven had suffered from malaria. At the time of my visit, fourteen of the twenty-two had had malaria; some of the others had been only a short time on the island. There had been five cases of blackwater fever, three of which had been fatal.

The cause of the malaria was A. maculatus, which I found breeding in large numbers in every stream and spring on the hillside except two. The more the hillside was cleared of vegetation to stop the malaria, the more extensive became the mosquitoes’ breeding area; and the measures taken to reduce malaria were really causing its increase. Accordingly, among my recommendations, I said: “With regard to the clearing of the jungle, I do not recommend this area be extended. Rather I would advise that all mosquito breeding places in the already cleared area be abolished.”

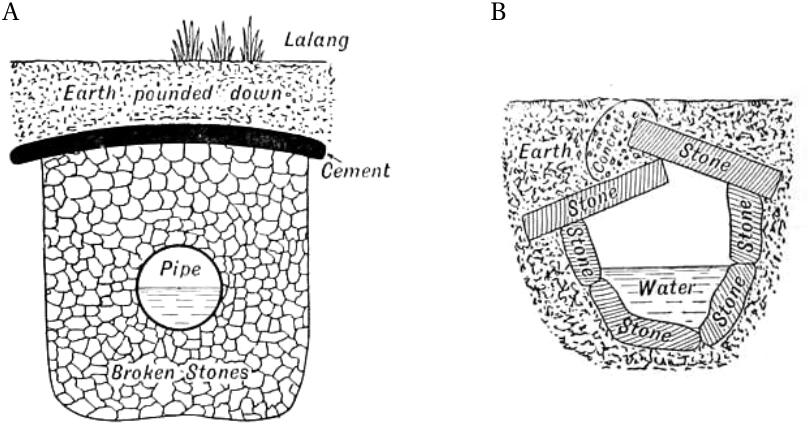

I also advised that the best way “to eradicate these mosquitoes is to put all the water on the hillside underground.” The hillside was a mass of granite boulders, some of large size, and others small; and most of it was very steep. In the steepest portions of the streams, I noticed the water was already finding its way underground among the boulders (cf. Figure 16.8), and that the water only appeared where the grade was less steep. Therefore I advised that this natural subsoil drainage be assisted; subsoil pipes being laid down where the water could not be drained in the natural channels. As a warning: “In work of this kind, where everything tiny, spring or trickle of water oozing from the hillside is a danger, the first essential is thoroughness. It is also important to remember that new springs may appear in wet weather, if the whole be done in a dry period.”

The same energy and thoroughness with which Mr. Galbraith had developed the factory, and created a model village, was brought to the anti-mosquito work. Writing on 19th December 1912, Mr. Galbraith said:

I had hoped to advise you before Christmas that we had sunk all the streams, but the weather has been so wet that we have been forced to suspend work until January. There are nineteen streams altogether to sink, besides a lot of little streamlets coming out of the foot of the hills along the seashore, and a dozen small outlets in the cutting behind the factory. We have cleared and exposed all the streams from end to end where they run on the surface, and have, so far, buried twelve, leaving seven large streams to finish. We have also done most of the work in the cuttings and cleared the seashore springs, and towards the end of January I hope to advise you we have finished.

The buried streams are holding fairly well notwithstanding the heavy rains (twice as much has fallen as in Singapore), and so far I don’t think we have had to repair 500 feet out of about 11,000 buried.

On 31st December he added:

I may say that at first some of our pipes were displaced, but this was partly due to insufficient depth and the incidence of heavy rain immediately after placing them, and they were almost perpendicular. We have since used a light mixture of sand and cement to cap all streams whether in pipes or only under rocks (as per sketch on next page), and any recent trouble we have had is due to silt blocking the stream and the water then bursting out; but this in turn was due to the storm water finding an entry higher up, and in time we expect to get over such accidents entirely.

I cannot say the improving health is yet due to the burying of streams—indeed, I do not think it is to any great extent—the number still open in our more or less restricted area is too large to stop breeding yet awhile. By March, however, I hope to show you the hills as dry as bones two days after the heaviest rain.

On 15th March 1913 I visited the island, and found the hills as dry as had been predicted, and the health greatly improved. Doubtless the heavy rains had helped to scour out the Anopheles, for they breed most freely in dry weather.

| Month | Labour force | Admissions | Outpatients | |||

| 1911 | 1912 | 1911 | 1912 | 1911 | 1912 | |

| July | 580 | 960 | 27 | 64 | 693 | |

| August | 530 | 860 | 34 | 68 | 535 | |

| September | 600 | 800 | 73 | 41 | 1761 | 412 |

| October | 760 | 890 | 117 | 33 | 1647 | 316 |

| November | 850 | 920 | 102 | 34 | 2348 | 230 |

| December | 690 | 860 | 85 | 22 | 1540 | 152 |

| January | 750 | 800 | 76 | 37 | 1158 | 249 |

| February | 808 | 840 | 44 | 36 | 751 | 183 |

The work had been done splendidly; the photos (Figure 16.8) show how steep the hillside is, and the difficulties that must have been overcome to make the drainage an engineering and anti-mosquito success. The experiment was promising. While there had been difficulties, owing to the steepness of the hillside, and the complete unfamiliarity with anti-malaria work of those who were responsible for its execution, all the difficulties had been successfully overcome by the splendid energies and intelligent appreciation of the essentials brought to the work by Mr. Galbraith, Mr. Grant, Mr. Day, and others of the staff; and all A. maculatus breeding places had been destroyed. There was in its favour that no danger came from the seaside of the settlement; the jungle-clad hinterland beyond the clearing was steep hill land and probably harmless—for no A. umbrosus was taken at my visits. In other words, no dangerous Anopheles now existed; or, if present, were so only in small numbers.

So I was hopeful of a great improvement in health by the end of 1913. But on my return to the East I found that the heavy fall in the price of rubber had practically closed down this jelutong factory, and only some 200 coolies were left. Soon afterwards I heard the factory had been sold, and the place abandoned. Caution must therefore be exercised in accepting an incomplete record; it never was to be completed. Yet for what they are worth, I give the total admissions and total out patients (Table 16.8); they eliminate errors of diagnosis, and any anti-malaria success should lead to a reduction of sickness from all causes. They are the last figures I received.

On the day of my visit in 1913 there was only one case of malaria in the hospital out of the whole labour force.

I think the story worth telling, both for the sake of the splendid fight against malaria, and for the guidance it may be to others in similar circumstances. On my last visit one member of the staff, in commenting on the difference in health between the time of speaking and a year before, said: “If ever again I have to do a job in a place like this, I will begin by killing the mosquitoes. The rest of the work will then be quite simple.”