| 4 |

Results of drainage of Klang Town and Port Swettenham, 1901 to 1909 |

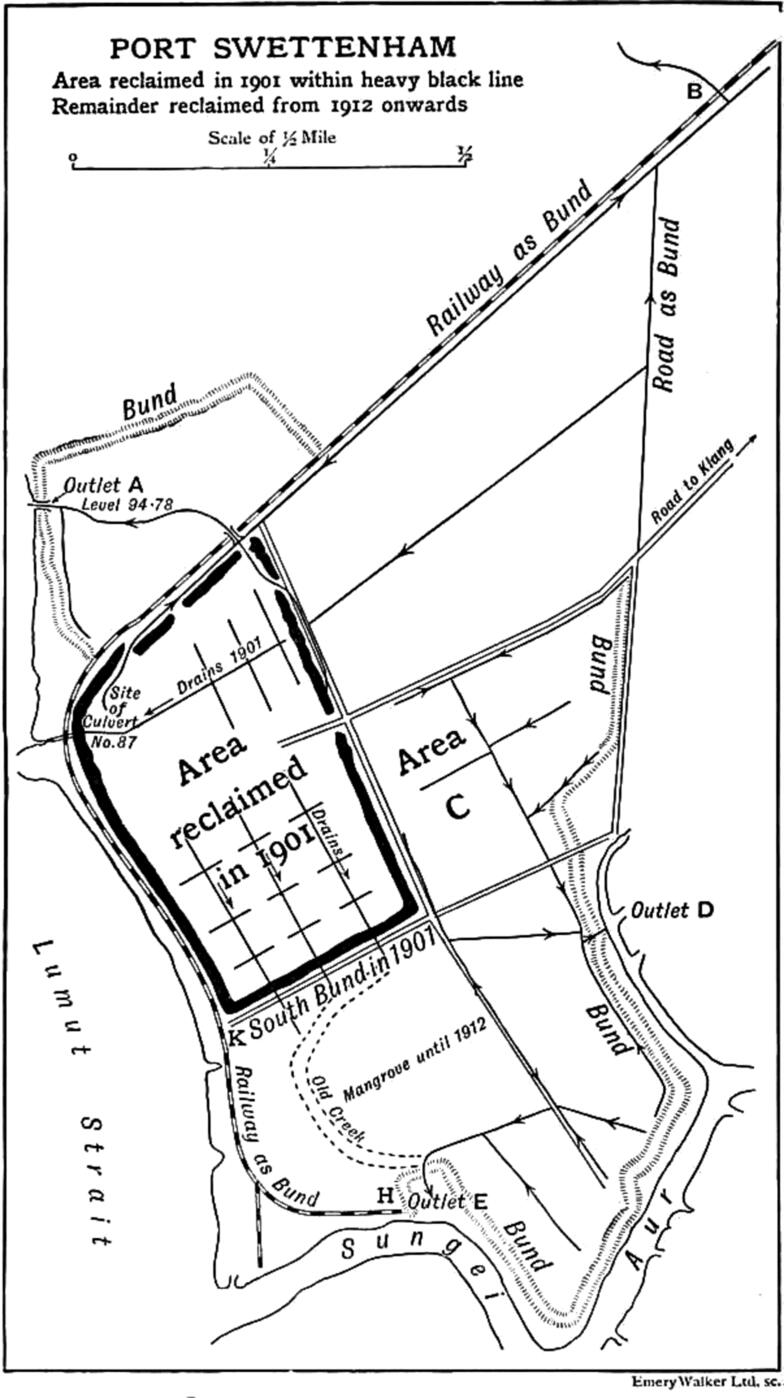

Two definite experiments were thus carried out on a considerable scale. The experiments were in areas quite different in physical characters: the one being a mangrove swamp which was reclaimed from the sea by bunds; and the other on and about low hills with swampy ground at the hill foot. Further, the two places were five miles apart. In 1901 they were probably the most malarial localities in the district.

It was not until December 1902 that a water supply was laid on to the towns; so this factor cannot have influenced the public health. That the improvement was not due to any general improvement is clearly shown by the continuance of malaria in the surrounding district, which thus acts as a control. The final proof, an undesirable one, is to be found in the recurrence of malaria, after a considerable period of freedom from the disease, in one of the places, when its drainage suffered interference and its inhabitants spread beyond the drained area; while in other places where the drainage was efficiently upkept no such recurrence has taken place.

| 4.1 |

Malaria treated at Klang hospital |

| 1894 | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | |

| Outdoor | 172 | 479 | 730 | 554 | 694 | 668 | 737 | 965 | 364 | 245 | 240 |

| Indoor | 91 | 112 | 158 | 128 | 163 | 251 | 467 | 807 | 403 | 219 | 298 |

| Total | 263 | 591 | 888 | 682 | 857 | 919 | 1204 | 1772 | 767 | 464 | 538 |

| Percentage | 20.4 | 28.9 | 25.0 | 19.7 | 25.2 | 20.2 | 24.9 | 38.8 | 20.4 | 12.1 | 11.1 |

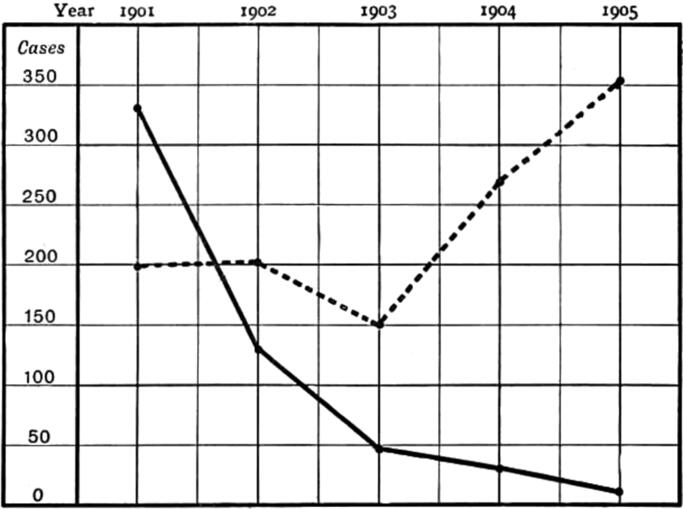

Table 4.1 shows the number of cases of malaria treated at the Klang hospital. From 1901 to 1904, the numbers of cases treated has greatly diminished. There was a subsequent increase owing to the increasing rural population. The incidence of the disease shown is striking, and Table 4.2 enables one to appreciate its cause.

| Residence | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Klang | 334 | 129 | 48 | 28 | 12 |

| Klang and Port Swettenham1 | 88 | – | – | – | – |

| Port Swettenham | 188 | 70 | 21 | 4 | 11 |

| Other parts of district | 197 | 204 | 150 | 266 | 353 |

- 1

- Certain persons lived some nights in Klang and some in Port Swettenham.

Situated as Klang and Port Swettenham are in a malarious country, their inhabitants are liable to infection should they spend a night away from home in the neighbourhood; and, on the other hand, imported cases of malaria are frequent in both towns. A difficulty arises in connection with the classification of the residence of new arrivals, who, giving a history of malaria shortly before coming to the town or port, develop symptoms again after they have been in residence over eight days, which length of time is generally regarded as the minimum incubation period of naturally acquired malaria. Such attacks are probably relapses; yet they might be the result of fresh infection acquired after arrival. Consequently, so as neither to underestimate the number of cases contracted in Klang and Port Swettenham, nor to overestimate the benefits derived from the anti-malarial works in Table 4.2, a residence of eight days free from symptoms brings the case under the heading “Klang and Port Swettenham.” In the light of these remarks, it is not uninteresting to note that of the thirty two cases recorded from the two towns in 1904, eight were probably imported cases having definite histories of malaria before arrival, three were Klang residents, who nine to twelve days before admission had slept out of the town,5 and eight were rickshaw pullers who frequently sleep away from home after a long journey instead of returning to town. In 1905, similar deductions have to be made.

| 4.2 |

Reduction in number of deaths registered |

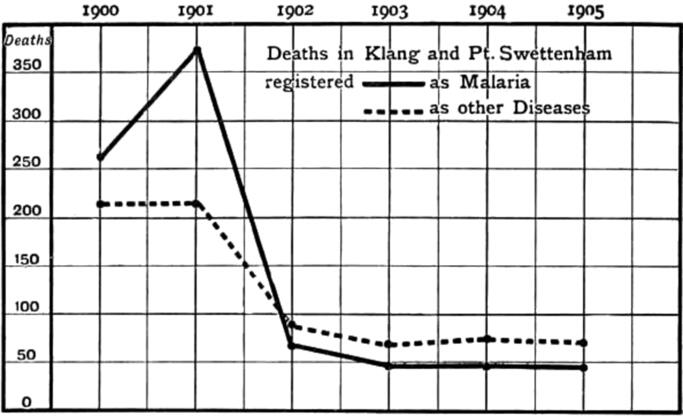

The reduction in the number of cases of malaria from Klang and Port Swettenham was accompanied by a remarkable fall in the number of deaths registered in the same places, while there was no similar reduction in the number from the surrounding district. These findings are summarized in Table 4.3, Figure 4.3, and Table 4.4.

| Cause | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Fever | 173 | 266 | 227 | 230 | 286 | 351 |

| Other diseases | 133 | 150 | 176 | 198 | 204 | 271 |

| Total | 306 | 416 | 403 | 428 | 490 | 622 |

It will be noted that the remarkable improvement in the health of the inhabitants occurred in 1902, immediately after the anti-malarial works had been undertaken.

| Cause | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Fever | 259 | 368 | 59 | 46 | 48 | 45 |

| Other diseases | 215 | 214 | 85 | 69 | 74 | 68 |

| Total | 474 | 582 | 144 | 115 | 122 | 113 |

Tables 4.4 and 4.3 show convincingly that subsequent to the anti-malarial works there has been a great reduction in the number of deaths, while in the district outside of the towns the number of deaths still increases. And it is evident, too, from Table 4.4, that the improvement is due mainly to the great reduction in the prevalence of malaria. Striking as this appears from the tables, the actual reduction has been, I believe, still greater, for among the deaths recorded as due to “other diseases” many were doubtless due to malaria. For in a malarious country the native informant is prone to report deaths, really due to malaria, as due to diarrhoea, dysentery, convulsions in children, or other terminal complications of malaria. Indeed, natives so frequently fail to recognise that their illnesses are connected with malaria that it has been found necessary to examine microscopically for malaria parasites the blood of all cases of diarrhoea, dysentery, anaemia, cardiac and renal diseases admitted to Klang Hospital, quite irrespective of whether or not the patient says he has had fever. That the native informant of death should make a mistake can, therefore, easily be understood. At the same time, the eradication of malaria to the extent that has occurred has undoubtedly improved the health of many of the town inhabitants; so that individuals, who in former years would have increased the mortality under “other diseases,” simply because they were in a low state of health consequent on malaria, are now able to resist the attack of such “other diseases,” or if attacked to overcome them and recover.

Although a good water supply was brought into the town in December 1902, and greater attention was being paid to general sanitation, I could not help believing that the improvement was due mainly to the diminution of malaria. As all deaths, with the exception of those certified by myself (up to 1907 the only qualified practitioner within twenty miles of Klang), are registered in accordance with the report of the friends, I regard the above tables as an “unsolicited testimonial” unconsciously given by the native community to the efficacy of the anti-malarial works in Klang and Port Swettenham.

Table 4.5 shows how much Government and its officers have benefited. From 12th July 1904 until December 1906, no officer in Port Swettenham suffered from malaria.

| 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | |

| Certificates | 236 | 40 | 23 | 14 | 4 |

| Days of leave | 1026 | 198 | 73 | 71 | 30 |

The results of the anti-malaria measures also resulted in financial loss to me from diminution of my private practice, from patients suffering from malaria contracted in Klang or Port Swettenham. In 1901 my private practice brought in $734 from patients suffering from malaria contracted in Klang and Port Swettenham. In 1904 it was nil, and it remained at this cipher until 1909 when cases were seen from Port Swettenham.

| 4.3 |

Children infected with malaria, Klang |

Unfortunately in 1901 no examination of the children was made to ascertain the percentage affected. I had, however, abundant evidence, both in my official and private practice, that they suffered severely. The disease frequently ran through a household. As an example I may mention that on one occasion (15th April 1901), when called to the Astana, the official residence of H.H. the Sultan of Selangor, to see a child with malaria, I asked if there were any others, and I found no fewer than 15 suffering from malaria.

Since 1904 I have made a series of examinations, at first of the blood, and latterly of the spleen and blood of children under the age of ten, differentiating according to the age. For the sake of simplicity I give only the totals. The examinations were made in the months of November, December, and January, but mainly in November and December. In Klang the children were examined both in the centre of the town and at its periphery.

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1909 | ||

| Blood | number examined | 173 | 119 | 91 | – | – |

| number with malaria | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | |

| % with malaria | 0.5 | 0.8 | 10a | – | – | |

| Spleen | number examined | – | – | 142 | 71 | 455 |

| number with malaria | – | – | 1 | 3 | 13 | |

| % with malaria | – | – | 0.7 | 42a | 2.8 |

- a

- These values appear erroneous, but they are given here as in the original (M.P.)

Convincing as these figures are of the absence of malaria in Klang Town, further inquiry showed that cases with evidence of malaria had only recently come to the town, and had contracted the disease previously to coming. For example, in 1904 the child with malaria belonged to a company of travelling players, and had had malaria in Kuala Lumpur; in 1905 the child with malaria was an inhabitant of Klang who two months previously had gone to Malacca for a month and, when there, contracted malaria; in 1906 the child with malaria had arrived only three days previously from Port Dickson; and in 1907 the examinations were made not by me personally as the others had been, but by a dresser, and no history is recorded of those with enlarged spleen.

In 1909, desiring to have the fullest evidence possible of the condition of the town, I personally went to every house in it, and also to all the schools, examining in all 463 children.6 Of the 308 examined in the schools five had enlarged spleen, giving a percentage of 3.87 of the school children; four were not residents of Klang, but came in daily; one from Kampong Quantan; one from 2ndmile Langat Road; one from Padang Jawa (by train); one from 21/2 mile Kapar Road.

Thirteen resided in the town; I give notes of their previous history: Seven were in the police barracks, four of whom had been transferred from Sepang, two from Jugra, and one had just arrived from Malacca; all gave a history of malaria before coming to Klang. Jugra and Sepang are notoriously malarious; two were in Government coolie lines, one having previously been in Batu Tiga—a very unhealthy place; and one had come from Kuala Lumpur where it had had malaria; two were children of an old watchman known to me for years who told me he had gone to an estate for three months, and when there both he and his two children had contracted malaria; the estate he referred to has a spleen rate of about 50%. One child had come to Klang only ten days previously from 21/2 mile Kapar Road; the mother informed me the child had fever before coming to Klang. One child came from an estate 20 miles from Klang known to me to be malarious.

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1909 | ||

| Blood | number examined | 187 | 76 | 100 | – | – |

| number with parasites | 1 | 0 | 5 | – | – | |

| % with parasites | 1.14 | 0 | 5 | – | – | |

| Spleen | number examined | – | – | 100 | 41 | 109 |

| number with enlargement | – | – | 2 | 9 | 9 | |

| % with enlargement | – | – | 2 | 21.9 | 8.9 |

It is to be remembered that Klang is constantly receiving people who are capable of infecting others with malaria if the connecting link be present. In Klang Hospital in the years 1906, 1907, 1908 respectively, 789, 1901, and 1537 cases of malaria were treated without any special precautions to prevent the spread of infection. One ward had been enclosed by wire netting, but when this decayed it was not replaced as there was no evidence that malaria was being spread from the hospital; for four years I had used mosquito nets in the hospital, but had given these up for Tamil patients as they would not use them unless compelled to do so; so that in 1907 when the maximum number of cases was treated there was the fullest opportunity for the infection spreading. No more severe test of the absence of malaria-carrying anophelines could be devised.

That the whole child population of Klang, except that known to have contracted malaria outside, should be completely free from all symptoms of the disease, is conclusive evidence of the value of drainage, and I would add here that not one single grain of quinine was given to any of the population except to patients actually suffering from malaria in hospital and in my official or private practice.

| 4.4 |

Children at Port Swettenham |

In 1901 there were thirteen children under the age of ten living in Government quarters. Of these nine contracted malaria within three and a half months of their arrival.

In 1904 the child who showed infection was found in the Police Station, and had only recently been transferred from Cheras, where she had fever. In 1906 I found evidence in the children of the recrudescence of the disease, simultaneous with its reappearance among the adults, as I shall relate.

For subsequent history see Chapter 22.