| 29 |

Results |

In the preceding pages, many instances of the control or partial control of malaria have been given; and it has been possible to associate directly the improved health with its cause, namely, some form of anti-malarial measure; it may have been open drainage, subsoil drainage, oiling, removal of people from the vicinity of jungle, or of jungle from people, or only the preservation of jungle. The number of people affected by any single operation has usually been small—perhaps only a few hundreds, although in places it has been greater. The sum total of the people is, however, considerable; so it may be worth gathering together the threads to see what manner of pattern they make.

| 29.1 |

Towns of Klang and Port Swettenham |

The only figures in my possession are those already given in the earlier part of the book. Table 29.1 lists the death rates for both towns from 1900 to 1905.

| Year | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Deaths | 474 | 582 | 144 | 115 | 122 | 113 |

The anti-malarial work was begun in 1901; and the figures indicate that from 1902 onwards, several hundred lives have been saved annually. In 1901, the population was only 3576 for the two towns; but they have never ceased to expand. Today, as determined by the recent food control census, the population of the town of Klang is over 20,000 people, and that of Port Swettenham nearly 6000. Can anyone doubt that, had the anti-malarial work not been done originally in 1901, and subsequently extended to cover the new population in the enlarged towns, many lives would have been lost annually, which have in fact been saved? In the eighteen years many thousands of lives must have been saved in the two towns.

| 29.2 |

Estates under the author’s care |

Figures are available of the health of the labour forces under my care. The estate hospital system was started in 1908; but my connection with the estates and researches into the causes of their ill-health began before that—at a time, indeed, when a healthy estate was practically unknown.

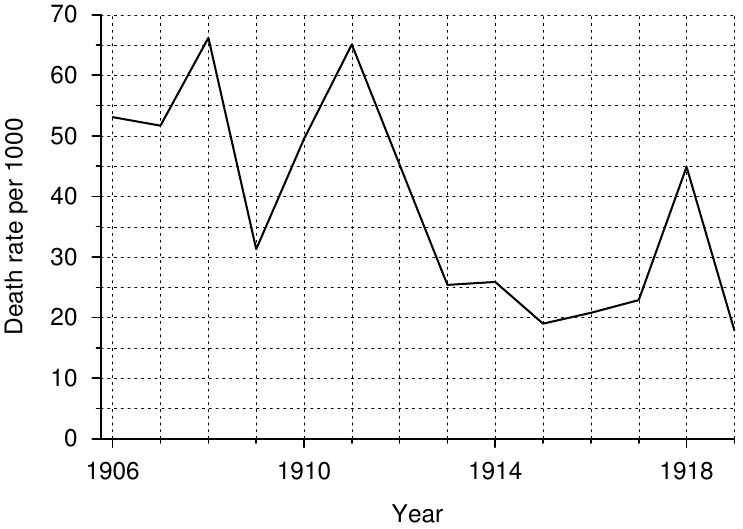

The figures in Table 29.2 are taken from the Official Returns printed in the Annual Indian Immigration Reports, except for the year 1919, which are compiled from the monthly returns sent to the Health Department. The Immigration Report for 1919 has not yet been published.

| Year | Labour force | No. of deaths | Death rates (‰) |

| 1906 | 9,939 | 528 | 53.1 |

| 1907 | 13,676 | 707 | 51.7 |

| 1908 | 15,898 | 1053 | 66.2 |

| 1909 | 16,982 | 527 | 31.3 |

| 1910 | 23,295 | 1155 | 49.5 |

| 1911 | 29,567 | 1924 | 65.1 |

| I912 | 32,394 | 1017 | 31.4 |

| 1913 | 38,248 | 975 | 25.4 |

| 1914 | 34,040 | 882 | 25.9 |

| 1915 | 30,456 | 572 | 19.0 |

| 1916 | 31,877 | 666 | 20.8 |

| 1917 | 28,954 | 664 | 22.9 |

| 1918 | 28,227 | 1269 | 44.9 |

| 1919 | 27,030 | 478 | 17.9 |

Figure 29.1 and Table 29.2 show an almost continuous improvement in health; and further improvement may be expected if the recommendations made are efficiently carried out, and the work already done maintained and extended.54 The improvement was checked, however, on several notable occasions. In 1911, about 30% of the deaths were probably due to the breakdown in the Penang Quarantine Station; of some 10,000 coolies in it, many suffered from cholera, dysentery, and malaria; many died in the station; and many others died soon after their arrival on the estates, and so raised the death rate. In 1916-17, a severe local outbreak of malaria almost doubled the death rate of the Kapar District. It was mainly due to the new railway—as I have described in Section 22.6.

In 1918, the world-wide epidemic of influenza affected the estates. In 1919, the disease was still haunting the coolie ships, and affected many coolies both in the quarantine station and on the estates. Despite this and the shortage of rice, the death rate for 1919 is the lowest on record.

Had the death rate remained at 66.2‰—the figures for the year 1908—the number of deaths occurring annually would have been as shown in table 29.3. The table also shows the number of lives presumably saved.

| Year | Labour Force | Actual deaths | Hypothetical deaths | Lives saved |

| 1908 | 15,898 | 1053 | … | … |

| 1909 | 16,982 | 527 | 1221 | 694 |

| 1910 | 23,295 | 1155 | 1537 | 372 |

| 1911 | 29,567 | 1924 | 1951 | 31 |

| I912 | 32,394 | 1017 | 2137 | 1120 |

| 1913 | 38,248 | 975 | 2524 | 1594 |

| 1914 | 34,040 | 882 | 2246 | 1364 |

| 1915 | 30,456 | 572 | 2010 | 1438 |

| 1916 | 31,877 | 666 | 2103 | 1437 |

| 1917 | 28,954 | 664 | 1910 | 1246 |

| 1918 | 28,227 | 1269 | 1862 | 393 |

| 1919 | 27,030 | 478 | 1783 | 1305 |

| Total | 10,949 |

Large as the saving of life has been according to this calculation, there is reason to believe that it is an underestimate; for we have seen that to increase the number of non-immune people in a malarial area increases the death rate at an ever-accelerating rate until it reaches 300‰ or over.55 The large increase of the population since 1908 would, therefore, have led to a death rate far in excess of the 66.2‰ on which the calculation is based; and the saving of 10,949 may be regarded as well within the truth.

The years have shown how even in a country notorious for its ill-health and high death rates, large, healthy, and prosperous labour forces can be built up out of very unpromising material: for the Indians who come here are usually poverty-stricken, often half-starved, and possess little resistance to disease.

| 29.3 |

The estate labour force of the F.M.S. |

Although ten years ago the control of malaria in rural districts was not considered practicable, and even today one hears talk of the almost insuperable difficulty and extravagant cost hardly making “the game worth the candle,” that has not been the attitude generally adopted in the F.M.S. On the flat land, the cost was often nothing; for a healthy site was selected instead of an unhealthy one, and the choice cost nothing. To quote the report of the Senior Health Officer for the year 1915:

Upon estates situated in the alluvial flats of the Coast Districts of Krian, Lower Perak, and Selangor, the health of the labourers is excellent, the only cause for anxiety is lack of good water in times of drought. …

Of hill land he says:

Anti-malarial measures of various sorts are universal upon most up-country estates. The most common is the prophylactic administration of quinine; many estates now spray with oil all swamps and ravines adjacent to the coolie lines, and a few have expended large sums on subsoil drainage.

Labourers are now generally housed in well-constructed lines built upon open clearings which afford good drainage; these have replaced the dark palm-leaf hovels on the edges of swamps or ravines, and closely surrounded by jungle or rubber which were formerly so common.

| Year | All nationalities | Indian labourers | ||

| Number | Death rate (‰) | Number | Death rate (‰) | |

| 1906 | … | … | 24,225 | 57.8 |

| 1907 | … | … | 36,092 | 55.7 |

| 1908 | … | … | 45,514 | 68.6 |

| 1909 | … | … | 49,924 | 46.8 |

| 1910 | … | … | 73,147 | 43.8 |

| 1911 | 143,614 | 62.9 | 110,000 | 65.1 |

| 1912 | 171,968 | 41.0 | 122,000 | 41.0 |

| 1913 | 188,937 | 29.6 | 133,072 | 30.4 |

| 1914 | 176,226 | 26.3 | 128,506 | 28.7 |

| 1915 | 169,100 | 16.7 | 120,190 | 20.9 |

| 1916 | 187,030 | 17.6 | 129,964 | 22.0 |

| 1917 | 214,972 | 18.1 | 140,346 | 22.4 |

| 1918 | 213,423 | 42.5 | 144,716 | 53.8 |

| 1919 | 237,128 | 14.6 | 160,657 | 18.6 |

Improved water supplies, increased and improved hospital accommodation, etc., have been provided for labourers, all of which have contributed to the lowering of the death rate; and it is impossible, from the data available, to disentangle the part due solely to the anti-malaria work, important though it must be. So I have contented myself with giving simply the death rate of the labour force in the F.M.S. since 1911. Each year, measures to improve health become more efficient, and without doubt further improvement will take place.

From 1906 to 1910, the figures for the Indian labourers include the indentured labour. There are no official statistics of estate labour other than Indian prior to 1911.

Taking the death rate of 62.9‰, and calculating as in the previous table, the number of lives saved from 1911 to 1919 is 58,102.

In this calculation, no account is taken of the lives saved before 1911 in the F.M.S.; nor have I reckoned the saving of life by similar work elsewhere in the Peninsula; in the Settlements of Malacca, Province Wellesley, The Dindings; or in the Unfederated Malay States, like Johore and Kedah. In these areas there are many thousands of estate labourers; on many occasions I have visited estates to advise on sanitary measures; and to my knowledge much excellent work is being done, and many lives saved. Of the work done in the city of Singapore, the chief city of Malaya, I will speak presently.

These results have been achieved not in a specially selected body of recruits, but among the poorest classes of India and China. The Indians, in particular, often arrive in the last stages of destitution, with hardly a rag of clothing for the adults, and none at all for even large children. The famines, which for ages have swept that land, have left their mark in the poor physique of the Tamils of Southern India; and even today famine drives whole families, of two or three generations, to Malaya. Many of the very old people are on the labour rolls, for occasionally they do a little light work; among these, as well as the infants, malaria has a deadly effect.

Great as the improvement in health has been, much still remains to be done; more estates can be made fit for Indian labour than now employ it; and the death rate of all can, I believe, be brought below 10‰.

| 29.4 |

Singapore |

The City of Singapore, placed by the foresight of Raffles one hundred years ago on the great highway to the East, has a population today of over 300,000 people. Even twenty years ago, as reckoned by the tonnage of the shipping, it was the seventh largest port in the world.

The entrepôt of the Great Archipelago and the neighbouring lands, it contains a curiously mixed population from East and West, from North and South; the main constituents of which are Chinese, Indians, and Malays. Arriving yearly by thousands, or passing through on their several ways to work in the surrounding countries and islands, such a population places peculiar responsibilities on the Health Department, and has made its work specially arduous. Back lanes, insanitary houses, food and markets, lodging houses, slaughterhouses, offensive trades, hawkers, and many other things demanding the activities associated with a Health Department in a large city had kept the staff busy; vast improvements had been effected; yet the death rate remained obstinately high. Great waves of malaria from time to time swept the city, reaching in June 1911 a maximum of 85.83‰. They defied every effort of the Department, and seemed to render fruitless almost all its work.

In 1911, malaria control was a much discussed subject. Many authorities were far from optimistic about the result of anti-mosquito work. In an able report, the Health Officer, Dr. W. R. C. Middleton, reviewed the whole subject; and subsequently, at his suggestion, and on the invitation of the Anti-malaria Committee, I visited Singapore and made recommendations for dealing with the most malarial district.

The work was admirably executed; it led to a rapid and permanent fall in the spleen rate; and since then it has been widely extended, although some areas remain to be done.

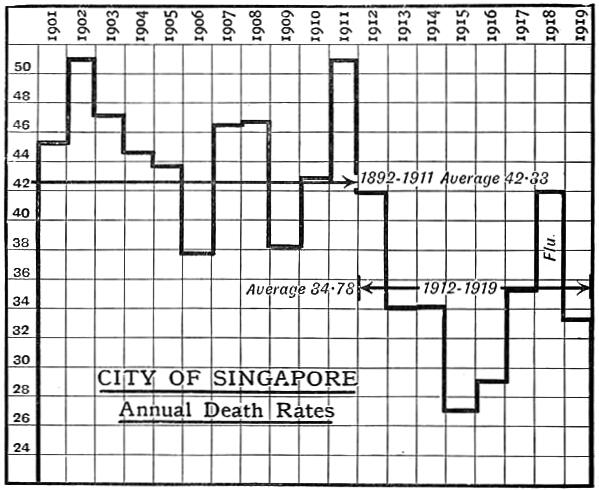

In such a shifting population, where, from inquiry, 30 to 50% of the hospital malaria admissions have been shown to be imported from beyond the city limits, the unravelling of death rates and an estimate of the effect of the anti-malaria work may appear a mere juggling with figures. Yet I think it is not so; for much information can be gained by a study of the monthly and annual variation of the death rates (see Table 29.7, further down). The outstanding fact is a great fall in the death rates since the anti-malarial work was begun in 1911, when compared with those of the previous twenty years (see Table 29.5 and Figure 29.2).

| Time period | Annual death rate (‰) |

| 1892 to 1911 | 42.33 |

| 1912 to 1919 | 34.78 |

| Difference | 7.55 |

If the average population between 1912 and 1919 be taken roughly as 280,000, the number of lives saved by all sanitary measures in Singapore in these eight years is 2100×8 or 16,800. What share of this is to be credited to the malaria control work?

Another outstanding fact, when we consider the figures, is the great rise in the death rates in the middle months of the year, usually beginning in May. Between 1901 and 1911 it occurs every year, with the exception of 1906; and in most years forms the curve, with which the reader must now be familiar, of malaria caused by A. maculatus, a mosquito, as Dr. Hunter proves, prevalent and of importance in Singapore. To show how serious these waves were, Table 29.6 shows the highest monthly rise between 1901 and 1911 (cholera and smallpox are excluded).

| Year | Highest monthly rate (‰) |

| 1901 | 80 |

| 1902 | 70 |

| 1903 | 60 |

| 1905 | 55 |

| 1909 | 50 |

| 1910 | 45 |

| 1911 | 40 |

| 1912 | 56 |

| 1913 | 42 |

| 1914 | 42 |

| 1915 | 28 |

| 1916 | 36 |

| 1917 | 39 |

| 1918a | 68 |

| 1919 | 38 |

- a

- Influenza.

Now if malaria control played any important part in the lowering of the general death rate, it would be reasonable to expect a reduction, if not the obliteration, of the annual malarial wave. The anti-malarial work was begun in 1911, and subsequently we do find a reduction in the magnitude of the malaria wave (cholera and smallpox are included). In 1912 the wave rose to 56‰.

To sum up: whereas prior to 1911 it was almost normal for the wave of malaria to sweep the death rate above, and often far above, 45‰, the wave has only reached that figure once—the influenza year 1918 is excepted—since the anti-malarial work was begun. As long as Anopheles breeding places exist in Singapore, and men who contract malaria elsewhere come into the city when ill, so long will the mortality rates show an upward curve in the malarial season. But when we recall the evidence given in the preceding chapters of this book—of malaria control, its seasonal waves, its effects on special and general death rates, the relationship of death rates and spleen rates—and then consider the lowering of the general death rate, the flattening of the mortality curve, and the fall in the spleen rate of Singapore, it seems to me we are irresistibly drawn to the conclusion that, more than any other factor, the anti-malarial work of the past eight years has led to the improved health of the city, and contributed to the saving of over 16,000 lives.

Yet, whatever the cause or complex of causes may be, which has lowered the death rate, the saving of thousands of lives is a fact beyond dispute, and one in which the Health Officers of Singapore may take a legitimate pride. It is, indeed, a splendid example of Preventive Medicine in the Tropics, and an inspiration for the great and difficult tasks that still lie before them.

There is a considerable mass of evidence to show that in the past twenty years, sanitary work generally, and particularly the control of malaria in conjunction with other measures, has saved 100,000 lives in the Malay Peninsula, and an enormous, but incalculable, amount of money.

| Year | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | April | May | June | July | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Max. |

| 1892 | 34.36 | 39.63 | 27.64 | 28.92 | 27.35 | 30.27 | 33.98 | 32.13 | 27.14 | 32.34 | 30.84 | 35.48 | 39.63 |

| 1893 | 38.08 | 32.54 | 33.99 | 35.24 | 43.75 | 44.10 | 38.08 | 34.75 | 31.36 | 30.94 | 28.16 | 34.74 | 44.10 |

| 1894 | 33.70 | 28.99 | 28.90 | 29.08 | 35.17 | 32.62 | 38.47 | 30.40 | 28.38 | 30.67 | 31.55 | 33.36 | 38.47 |

| 1895 | 32.35 | 26.53 | 31.43 | 45.03 | 51.50 | 72.54 | 50.71 | 43.20 | 31.37 | 38.95 | 36.99 | 44.50 | 72.54 |

| 1896 | 46.80 | 44.40 | 44.40 | 54.50 | 63.20 | 54.30 | 48.19 | 49.51 | 44.56 | 44.24 | 40.12 | 37.26 | 63.20 |

| 1897 | 41.90 | 32.10 | 38.80 | 43.50 | 46.80 | 46.30 | 49.10 | 41.50 | 42.20 | 41.50 | 34.70 | 32.00 | 49.10 |

| 1898 | 30.78 | 26.41 | 26.01 | 28.48 | 36.71 | 39.76 | 44.43 | 39.94 | 34.79 | 34.91 | 34.97 | 39.76 | 44.43 |

| 1899 | 37.58 | 29.83 | 33.14 | 32.04 | 35.93 | 40.53 | 37.04 | 32.56 | 30.35 | 35.29 | 34.42 | 37.71 | 40.53 |

| 1900 | 34.83 | 29.19 | 35.85 | 36.53 | 42.29 | 46.41 | 44.43 | 40.65 | 45.00 | 40.76 | 52.22 | 50.81 | 52.22 |

| 1901 | 44.54 | 34.42 | 36.04 | 40.55 | 49.00 | 50.33 | 50.50 | 49.40 | 44.66 | 47.90 | 50.10 | 45.64 | 50.50 |

| 1902 | 46.25 | 35.72 | 40.87 | 62.44 | 85.31 | 61.82 | 53.89 | 40.42 | 45.28 | 47.55 | 48.00 | 47.21 | 85.31 |

| 1903 | 45.33 | 44.66 | 46.21 | 44.66 | 65.67 | 51.74 | 48.59 | 44.50 | 46.27 | 44.94 | 42.62 | 41.79 | 65.67 |

| 1904 | 36.59 | 34.31 | 35.94 | 42.49 | 54.83 | 48.77 | 53.26 | 53.30 | 44.27 | 45.68 | 40.27 | 45.73 | 54.83 |

| 1905 | 43.32 | 37.91 | 45.91 | 43.74 | 48.41 | 51.54 | 51.16 | 41.51 | 35.10 | 42.42 | 39.39 | 44.54 | 51.54 |

| 1906 | 36.86 | 35.45 | 41.54 | 46.06 | 40.76 | 36.86 | 40.65 | 32.54 | 34.99 | 38.10 | 34.52 | 37.05 | 46.06 |

| 1907 | 34.85 | 26.95 | 36.38 | 42.49 | 51.25 | 54.00 | 53.75 | 68.68 | 50.85 | 50.54 | 44.99 | 42.80 | 68.68 |

| 1908 | 33.77 | 32.37 | 37.82 | 42.06 | 56.00 | 51.06 | 50.31 | 49.46 | 46.26 | 50.11 | 61.40 | 50.81 | 61.40 |

| 1909 | 43.03 | 29.16 | 31.86 | 36.61 | 42.69 | 39.31 | 37.79 | 36.81 | 41.56 | 43.97 | 45.00 | 34.90 | 45.00 |

| 1910 | 37.04 | 34.30 | 35.31 | 35.31 | 47.53 | 43.68 | 55.56 | 50.56 | 48.15 | 44.59 | 43.15 | 39.54 | 55.56 |

| 1911 | 40.07 | 28.93 | 36.37 | 49.73 | 80.19 | 85.83 | 60.27 | 47.51 | 44.14 | 50.06 | 44.28 | 43.49 | 85.83 |

| 1912 | 40.26 | 33.81 | 35.02 | 42.09 | 50.32 | 55.96 | 50.23 | 44.42 | 39.59 | 37.89 | 38.47 | 36.05 | 55.96 |

| 1913 | 33.41 | 25.91 | 29.23 | 31.54 | 36.73 | 38.30 | 38.26 | 33.07 | 33.24 | 38.13 | 36.16 | 35.51 | 38.30 |

| 1914 | 33.65 | 28.54 | 31.14 | 35.90 | 42.15 | 40.62 | 36.37 | 31.56 | 28.41 | 33.52 | 33.35 | 34.11 | 42.15 |

| 1915 | 35.74 | 28.48 | 28.07 | 26.00 | 26.53 | 26.20 | 25.95 | 28.98 | 25.83 | 27.36 | 24.13 | 25.42 | 35.74 |

| 1916 | 24.32 | 21.25 | 23.80 | 31.07 | 36.45 | 34.55 | 33.42 | 30.59 | 27.84 | 29.70 | 27.64 | 30.47 | 36.45 |

| 1917 | 30.78 | 30.27 | 33.89 | 34.28 | 37.75 | 38.73 | 38.50 | 38.58 | 39.60 | 38.50 | 33.81 | 34.36 | 39.60 |

| 1918 | 39.68 | 33.70 | 33.16 | 37.49 | 45.31 | 44.55 | 51.33 | 35.27 | 30.36 | 69.05 | 50.72 | 34.35 | 69.05 |

| 1919 | 32.32 | 26.50 | 26.20 | 27.77 | 32.47 | 35.79 | 38.44 | 38.85 | 36.17 | 35.53 | 35.61 | 35.79 | 38.85 |

| 29.5 |

Panama |

Critics of the work done by the Americans in Panama sometimes say that what was accomplished there would be impossible under less special conditions. They contend that the canal was built primarily as a war measure to safeguard the interests of Americans; cost was of minor importance, and the work was backed by the whole assets of the United States Treasury. They point out that the area dealt with was only 50 square miles, and declare that the population was under an iron discipline not attainable in other countries.

These criticisms may, or may not, be strictly true; but, if true, they are answered, I think, by the work done in the Malay Peninsula. Here the work has been done by Government in the ordinary course of its sanitary administration; and by the Estates, which are commercial undertakings, whose policy is influenced by price of the produce they sell. The area of the operations extends to thousands of square miles; indeed the area over which the estates under my supervision are scattered is more than 1000 square miles. The population of the estates is under a certain amount of discipline; but, the labour being free and not indentured, the discipline is far from being of the military variety.

In Malaya, the control of malaria has been attempted successfully under many different conditions; from small rural populations of two or three hundred people on estates, and in small towns of three or four thousand inhabitants like Klang to a city like Singapore, with over a quarter of a million people; the complexity of the entomological aspect of the problem, from the number of species carrying malaria under different conditions, has no parallel in Panama; the number of lives already saved by the work annually is greater in Malaya than in the Isthmus; and I might add that the work was begun here some years before it was started there.

The work in Panama is, in my opinion, without question the most brilliant achievement in Preventive Medicine which the tropics, and for that matter the whole world, has seen; but such a statement in no wise detracts from the value of what has been accomplished in Malaya. The work in the two places may be compared to the advantage or disadvantage of either, as the critic may be biassed. In truth, they are to be regarded as complementary; each developing on the lines best calculated to achieve its object in its own peculiar circumstances. They represent different phases or stages in progress towards the time when man shall conquer the tropics by stamping out its diseases; and these rich lands, many of the most fertile on the face of the earth, shall pour out, in unstinted measure, of their abundance for the welfare of the human race.