| 23 |

Screening |

| 23.1 |

Experiments with a hospital at Jeram |

In October 1900, a Beri-beri Convalescent Hospital at Jeram was opened. It is on a stretch of sandy shore. But at Jeram, as in Italy, the shifting sand is continually blocking the drains, so much so that one tide will undo a week’s work. In fact, the task of keeping them open was abandoned, and the water was led off by a circuitous route. The result was that the patients suffered from malaria. When I took charge in January 1901, I went through all the case sheets of the patients who had contracted the disease and tabulated the results. From 1901 to 1907 the record was kept continuously. The population was under complete control; its number was definitely known, and in many ways it presented a very satisfactory field for observation.

The patients were provided with mosquito nets from the beginning, and yet, in spite of these, they continued to suffer from malaria.

It was then decided to make the hospital mosquito-proof. This appeared in the estimates for 1902 and was actually completed on the 17th November 1902. The gauze was of iron wire; the sea air rusted it, and on the night of 11th October 1903, a strong wind carried it away. It was never replaced. From 1st January 1905, no malaria case was admitted into the hospital, in order to see to what extent the local admissions of malaria influenced the spread of the disease in hospital. From the beginning of 1906 all the beri-beri patients were on a weekly dose of 10 grains of quinine.

In this way I, have tried to gain some idea of the relative importance of some of the factors influencing the epidemic. Table 23.1 shows the figures obtained.

| Condition of hospital | Period (no. of months) | Patients attacked | |

| Number | Avg./month | ||

| Mosquito nets only | Oct. 1900 to Nov. 1902 (26) | 75 | 2.87 |

| Ward mosquito-proofed | Nov. 1902 to Oct. 1903 (11) | 5 | 0.45 |

| Mosquito nets only | Oct. 1903 to Dec. 1904 (15) | 48 | 3.20 |

| Malaria cases not admitted | Jan. 1905 to Dec. 1905 (12) | 20 | 1.66 |

It is to the third table row particularly to which I would direct attention. It will be seen that malaria was greatly reduced by the use of the gauze, and increased at once when the gauze was removed. That any malaria occurred is probably due to the purposely lax conditions which prevailed. No restraint was put on the patients to be indoors after sunset. Two double doors permitted entrance and exit after 6 p.m., and the patients often wandered to the native village only about a quarter of a mile away.

I was proposing to prevent the possibility of outside infection by locking the hospital after 6 p.m. when the storm put an end to the experiment. The value of this experiment in my eyes is that the conditions were lax enough to permit of their being applied to coolies on an estate, or to coolies engaged on Government construction work, such as the making of railways or water works, where malaria is as great a scourge as it is on the worst estate.

With these results I accordingly approached the Government in 1904 with a suggestion for an experiment on the above lines, on the proposed extension of the Klang Water Works. Dr. E. A. O. Travers supported the suggestion, and Government instructed the State Engineer to include my requirements in his estimates.

| 23.2 |

A failed experiment on an estate |

There was some delay in the preparation of the plans of the new works; and the Government then, at my suggestion, sanctioned a special vote of $2000 (about £240) to be spent on mosquito-proofing lines on an estate. I chose the most unhealthy spot I knew. The object of the experiment was, of course, not to test the mosquito theorem, but to discover whether lines could be built which would be sufficiently mosquito-proof to reduce malaria, and yet would be acceptable to the ignorant coolie and in which he would be willing to live.

The spot chosen for one of the lines, the only one to be completed, was on a saddle at the head of two ravines, one of which was opened and drained by the estate, but still contained A. maculatus, and the other was unopened and undrained jungle. There had been trouble in building the lines originally; two contractors who tried to build the lines died from malaria, since they refused to take quinine, and the first gang of coolies who inhabited it were practically exterminated by malaria. All children under the age of fifteen were found to be infected with malaria on blood examination. These coolies were soon removed. Ultimately the lines were finished. No coolies on the estate would inhabit them; and further, it was desirable to put in new coolies who presumably were free from malaria. A gang of coolies was put in during November 1907.

They were not given quinine daily like the other coolies, but were carefully examined by the dresser of the estate, and I paid as many visits to them as possible. Unfortunately my health was not satisfactory at the time, and I had to go on leave. Before going, however, I was able to determine that it was impossible to find anophelines or other mosquitoes within the lines, although my observations, extending over a year, had shown that before proofing it was always possible to take about ten anophelines by looking through all the rooms, and other mosquitoes were much more numerous. The mosquito proofing, therefore, certainly succeeded in reducing the number of anophelines within the lines.

Within a short time the coolies became aware of the character of the lines they were in, and asked to be removed. On one occasion I was told by a coolie that on the previous night a devil had been heard knocking on the walls.

I am unable to give any evidence as to the termination of the experiment. The manager stated that, as long as the coolies were there, they did not suffer from malaria, but that on account of their terror it was impossible to keep them there for long. He strongly suspected they left the lines at night and went to other unprotected lines. He also informed me that the coolies said the lines were very hot, and that at night they would often lie outside in a blanket. The lines had a wooden ceiling, and as they were more enclosed than other lines, it is probable they were hot.

I had unfortunately to leave this experiment, and therefore am unable to draw any conclusions. Doubtlessly, the F.M.S. Government will take an early opportunity of testing the value of mosquito-proof lines on the railway extensions now being carried out towards the Siam States, where malaria will doubtlessly be as serious an obstacle as it has been in the previous railway and other public works.

Although I suggested to the Malaria Advisory Board that it should undertake an experiment with screened lines, nothing has been done.

| 23.3 |

Screened houses |

On a malarial estate in Johore, where there were difficulties in getting healthy sites, I recommended that a bungalow and servants’ quarters be screened. The manager was afraid that it would be uncomfortable, and that he would feel “cribbed, cabined, and confined” in it. However, I advised the whole building should be done; only two doors opening to the outside were to be left. There being no internal screened doors, the occupants could move about in the house as usual.

A year’s trial convinced the manager that his fears were without foundation, and that screening was of value; and three other bungalows on the estate were screened. This was in 1914; since then, sixteen bungalows on other estates in the neighbourhood have been screened, which is the most satisfactory proof of the value of screening.

Dr. Hickey, the medical officer of these estates, sends me an interesting letter full of details, from which the following are excerpts:

As regards screened houses, there has never been any doubt in my mind about their success. Not only on Segamat, but on Labis, Jenang, Genuang, Rubber Estates of Johore, and Johore Rubber Lands, Batu Anam, they have proved a success. … I know what a difference screening has made to my bungalow; in 1912 and 1913; I suffered a good deal from malaria.

Other anti-mosquito measures are employed on the estates, which have improved their health, but Dr. Hickey adds:

I quite realise that malaria is gradually becoming less prevalent on the estates here, but the improvement in the health of those who occupy screened houses is really wonderful. Men ask for screened houses now.

| 23.4 |

Screened hospitals |

On an estate where many anophelines exist, the malaria patients in hospital are a reservoir of parasites which soon infect the anophelines. These infect and reinfect the malaria patients, as well as patients coming in with other diseases; nor do the hospital staff escape. Consequently the administration of the hospital becomes difficult; and patients recover slowly, if, indeed, they do recover.

Protection from the insects is, therefore, a necessity. At first this was attempted by mosquito nets over the beds; but with natives the nets are ineffective, and it is usual to find a number of mosquitoes within them each morning. In fact, these nets are so effective as traps that, when I desire to get specimens of adult insects in a place, I search the nets at daybreak; for I know of no better way of getting a haul.

In view of the failure of the nets, in 1911 I advised an estate to screen its hospital. This was done, proved a success, and now there are screened hospital wards on six hill estates where malaria at one time was severe. Only one door is allowed at each end of the ward in which it is rare to see an insect. If any get in, they are caught in a bottle containing a plug of cotton-wool sprinkled with chloroform.

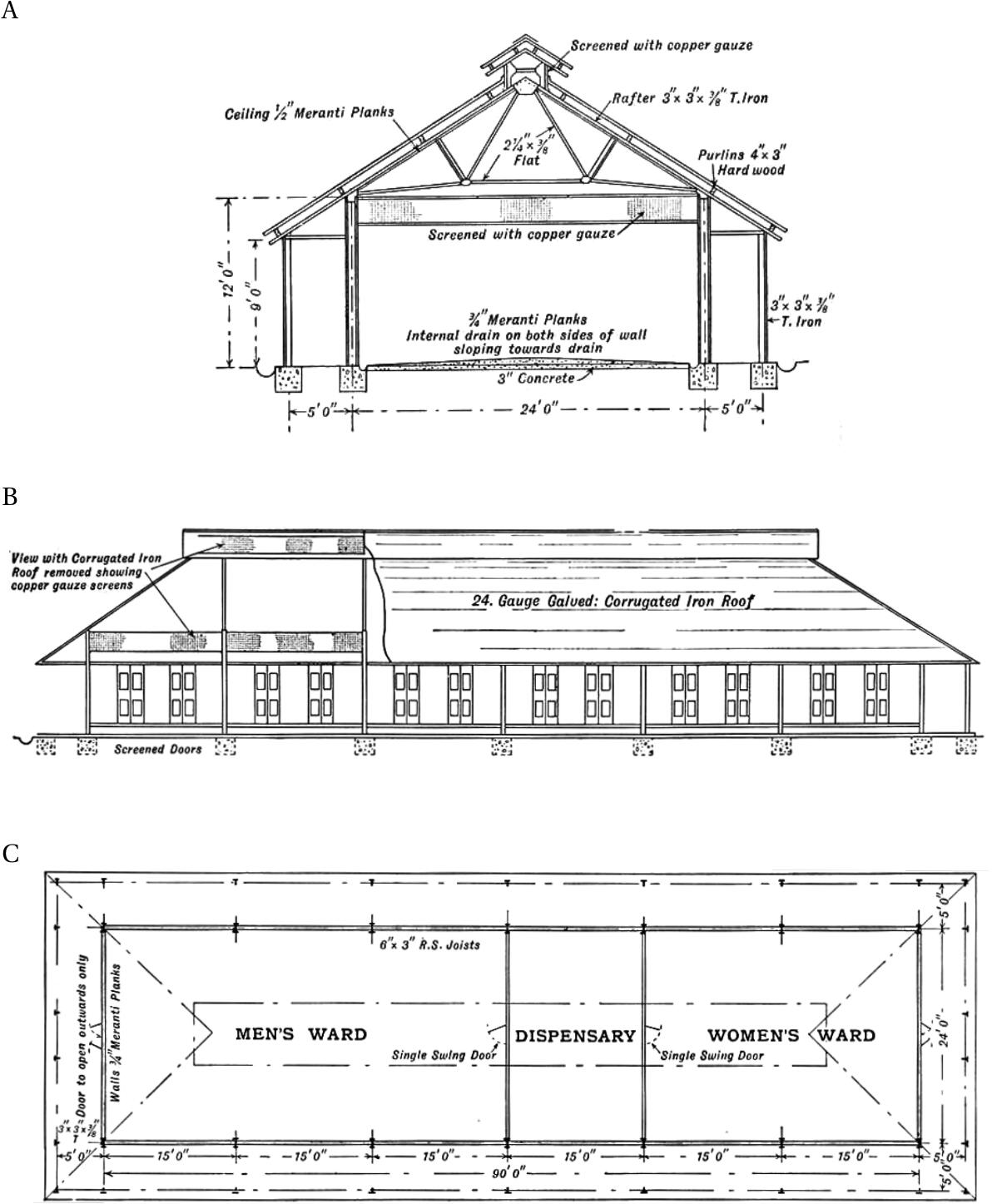

The plan shown in Figure 23.2, kindly supplied by Messrs. James Craig, Ltd., who have built several of these hospitals, shows the details of the ward. One or two points call for comment:

- It is important that the screening of the jack roof be by two vertical strips of gauze, and not by a horizontal strip as first suggests itself; for a horizontal strip catches and retains much dust, while vertical strips are relatively self-cleansing.

- The doors should open outwards only, so that any mosquitoes resting on them are driven outwards when the door is opened. Double doors have not been found necessary.

- The drain must be inside the ward, as it is not possible with this design to wash the floors, and allow the water to escape under the side walls of the ward.

- Attempts were made to retain a screened space of 6 or 8 inches along the floor of the ward; in some hospitals the screening was on a hinged frame, in others it was fixed. The hinged screening has been most unsatisfactory; the fixed screening rather less so. In future I would have no screening within a foot of the floor; because it is liable to be damaged when the floor is washed.

- In Panama nothing but an almost pure copper, or alloy free from iron, withstood the climate; this was due to the screening being used on the outside of the verandah and exposed to rain and sun. In some hospitals here, the gauze used has been iron; it is placed so as not to avoid rain or sun, and is standing the climate well; indeed, in one hospital the gauze originally supplied in 1911 is still in use, and it has not yet been necessary to renew it in any hospital. The cost of screening a hospital depends on the area and the cost and quality of the gauze.

As a result of my experience of screened hospitals here, and from what I saw in Panama, I am strongly of opinion all native hospitals in this country should be screened instead of being supplied with mosquito nets.