| 19 |

On the possibility of altering the composition of water and the anophelines breeding in it37 |

It has long been established that mosquitoes, including the anophelines, exercise discrimination in the selection of water in which their larval stage is passed. Each species prefers its own special type or character and quality of water as a breeding place. Some have a wide range, others are peculiarly selective. A. maculatus is one of the latter. In Malaya it is found exclusively in hill streams, and in the springs which feed these. I consider that the eggs are laid in, and that the larvae prefer, the shallowest waters; indeed they are most numerous in ground with so little water on it that, in order to take the larvae, it is often necessary to make an excavation in the earth into which the water from the surrounding ground flows, carrying the larvae with it. As these springs are very common at the head of a ravine, the presence of this mosquito in them probably accounts for the well-recognised danger of living at the head of a ravine. The old explanation for this was that mists were carried up the ravine, and naturally struck with special force those living at its head.

From these springs the larvae are carried down the streams; but they cannot be entirely washed out, even by the strongest currents or rains. I have found them in a drain after a 2-inch shower. When one attempts to take them they often wriggle completely out of the water onto the damp ground. I have watched them at play in a clear pool at the foot of a rock, down which water was flowing with considerable force, since the rock sloped to the pool at an angle of 45° and its face was a foot long. The current of water was still further increased in strength by the rock being funnel-shaped, and all the water coming down the face was gathered into a solid stream as it entered the pool. The larvae were playing, not exactly like trout, head to stream, but were floating round in the current, and every now and then one would swim right into the stream, up it for a short distance, and then hang on to the side of the apparently bare rock in the full strength of the current.38

As A. maculatus is never found on the flat land, it is obvious that this mosquito requires water of a special character; such as water well aerated and quite free from vegetable decomposition.

In May 1909, having accepted an invitation from the late Mr. C. Malcolm Cumming, Chairman of the Planters’ Association of Malaya, to visit a Tamil settlement which he had successfully established, I motored into Negri Sembilan and saw the padi swamps, rice fields, or sawahs39 there. These consist of valleys, the whole bottom of which have been rendered flat, so that they can be irrigated by the waters coming down the valleys. They seemed to me ideal breeding places for anophelines, and I asked if they were unhealthy. I was assured that the inhabitants were extremely healthy, and that malaria was unknown. It occurred to me then that the process of padi cultivation must alter the composition of the waters in some way, so that what I should regard as the normal inhabitant of the valley stream, namely A. maculatus, had been driven out.

The following day, when passing an estate, Mr. Cumming informed me that the estate had been healthy until Tamils had been introduced, and since then had been extremely unhealthy. I remarked that the valley through which we were passing was very swampy, and he then told me that it originally had been sawah, but that the Malays now were employed on the estate, where they got better wages.

It appeared to me that if there was any truth in the statement that sawahs were healthy, then the abandonment of the sawah, and not the introduction of the Tamil coolie, was responsible for the outbreak of malaria on the estate. The idea was that by abandoning the sawah, the A. maculatus had been enabled to return to the valley. It was obvious, too, that it might be a method of treating ravines on rubber estates where the drainage was difficult, or where weeding was so expensive that it might be an economy to abandon the ravine, if this could be done without impairing the health of the labour force on the estate. The matter appeared to be of importance economically, and called for investigation.

I therefore spent that night on the edge of a sawah. In the evening, three anophelines were taken—one A. fuliginosus, one A. sinensis, and one A. rossi. Under ordinary circumstances, I should have expected to find at least one A. maculatus. I learned that this sawah was considered healthy. In the morning I examined fifty Malay children at Kampong Batu Malay School, of whom twenty (or 40%) had enlarged spleens.

So far these results appeared to bear out my conjecture, but I had no opportunity of further investigation until August, when I went to the Krian irrigation padi fields, and also to those at Bukit Gantang. I was only able to spend a week on the work at that time, and was unable to return to finish it until November.

The investigation consisted of an examination of the children and of the species of anophelines breeding in the waters, and found in the houses in the two places. Although both were padi swamps, the most extraordinary difference in the health of the two places was discovered, and a difference in the species of anophelines was also found.

| 19.1 |

Krian irrigation padi fields |

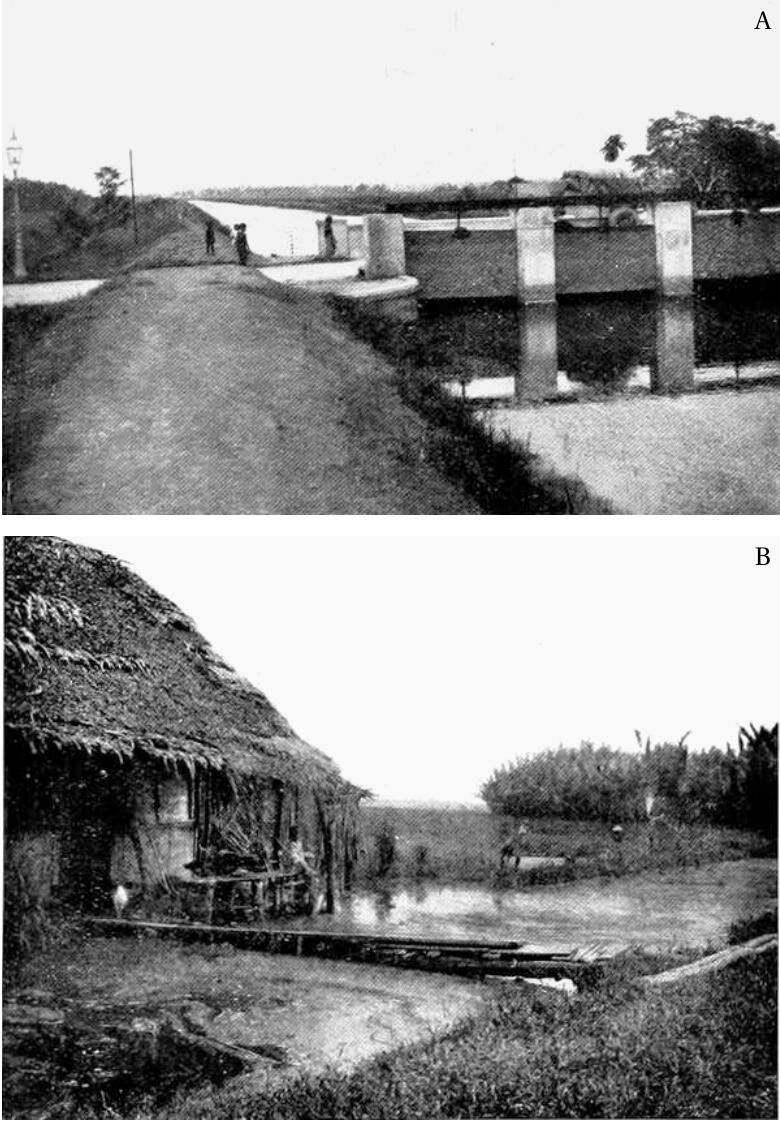

This irrigation scheme, carried out at the cost of about 11/2 million dollars, was completed in 1906, and was at once a financial success. It enabled the people to reap a good crop in a dry year, when their neighbours, outside the irrigation area, were suffering from want of water. The area irrigated is about 60,000 acres.

The water supply is from two rivers, the Sungei Merah and the Sungei Kurau, which are dammed at a pass in the hills, so that by overflowing their banks they spread over ten square miles of jungle. The effect of the constant water on the jungle has been to kill it out slowly, and in passing along the railway, which crosses the reservoir, one sees comparatively few of the larger trees now alive, while many dead ones are still standing.

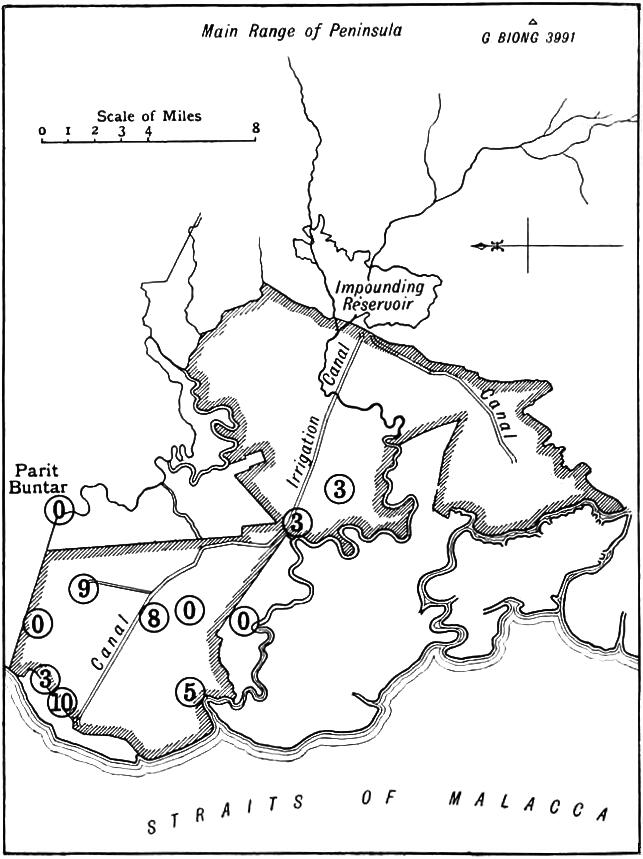

These rivers have already traversed considerable distances before they reach the impounding reservoir, but the waters of both have originally come from the hills. From the impounding reservoir the water is led by the usual canals, and after flowing over the land is led off by drains to the nearest rivers as will be seen from the map (Figure 19.2).

| 19.2 |

Health of the children in Krian |

During my two visits I examined 304 Malay or Tamil school children and 47 estate Tamil children; and the late Dr. Delmege, the Government Medical Officer, kindly furnished me with the figures of 367 school children whom he examined. Out of the total 718 examined, only 20 (or 2.7%) had enlarged spleen. The details of the examinations are given in Table 19.1.

| Observer | Place and group | No. examined | No. enlarged | % enlarged | |

| Dr. Delmege | P. Buntar— | ||||

| Malay boys | 52 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Malay girls | 39 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| English, mixed | 28 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sungei Star | 47 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| " | 31 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sungei M. Aris | 59 | 2 | 3.3 | ||

| Sungei Labu | 28 | 3 | 10.0 | ||

| Titi Seron | 57 | 5 | 8.7 | ||

| Jalan Bharu | 26 | 2 | 7.6 | ||

| Dr. Watson | Bagan Serai— | ||||

| Malays | 66 | 3 | 4.5 | ||

| Tamils | 34 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Telok Maiden | 71 | 2 | 2.7 | ||

| Jin Heng Estate— | |||||

| Tamils | 47 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sungei Siakap | 65 | 3 | 4.6 | ||

| Sungei Bharu | 68 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Grand total | 718 | 20 | 2.7 | ||

A reference to the map will show that these examinations cover practically the whole district, and can be considered quite representative of it. They show conclusively that this irrigation area is to a striking degree free from malaria. This is the general idea, and Dr. Delmege writes me as follows: “I quite agree with you that there is very little, if any, malaria contracted in the padi fields.”

| 19.3 |

Anophelines of Krian irrigation |

The anophelines of the Krian district were found to be A. rossi, A. sinensis, A. kochii, and A. barbirostris. The two last-named mosquitoes are found breeding freely in the irrigation channels and in the padi-fields. They are also found in the houses, where they feed freely on the inhabitants. The low percentage of infected children in a place in which adult anophelines are so abundant is strong evidence that these species do not carry malaria; or, if they do, they act as extremely inefficient hosts for the parasite. The fact that the percentage of children with enlarged spleens is practically the same as in Klang, and on the healthy estates, where a history was obtained of the affected children, mostly immigrants, who had suffered from malaria before their arrival, makes it extremely probable that the affected children in the Krian district had contracted their malaria outside its limits.

I was unable to make any investigations into the health of the children on the estates in the Krian district beyond that of the one mentioned, which was on the opposite side of a road from the irrigation area, and where the spleen rate of the forty-seven children was found to be nil. An examination, however, of the death rates of the estates on the flat land of Krian is so low that malaria can hardly be a serious consequence. One estate, however, which is shown to be on the edge of a Government forest reserve has a death rate of 100,40 evidence that malaria is to be found near to the jungle in Krian as in Klang, and that opening of the land gives freedom from malaria there also.

| 19.4 |

Bukit Gantang valley rice fields |

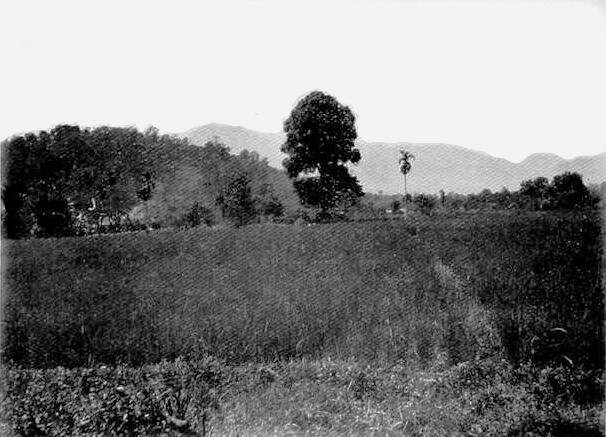

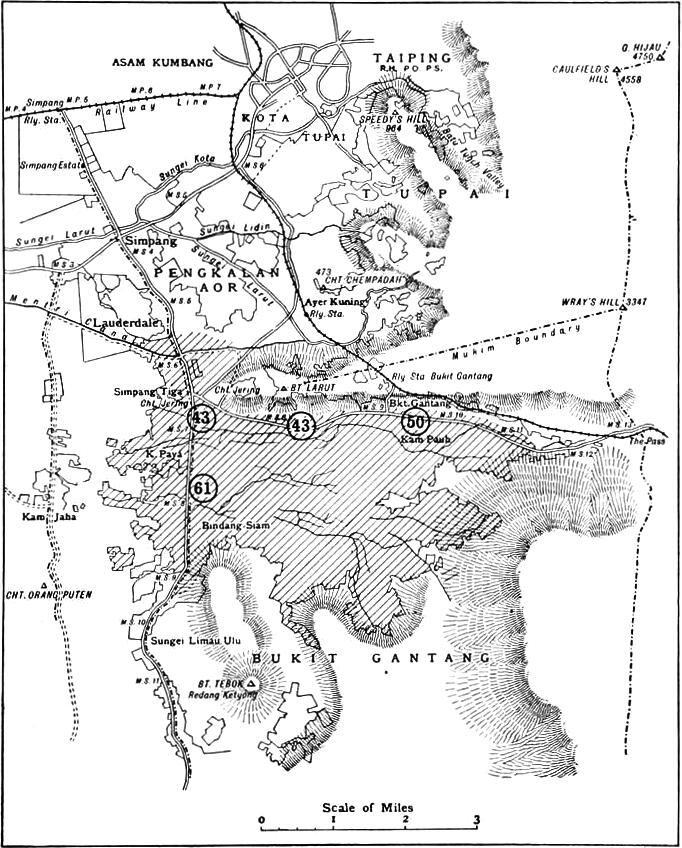

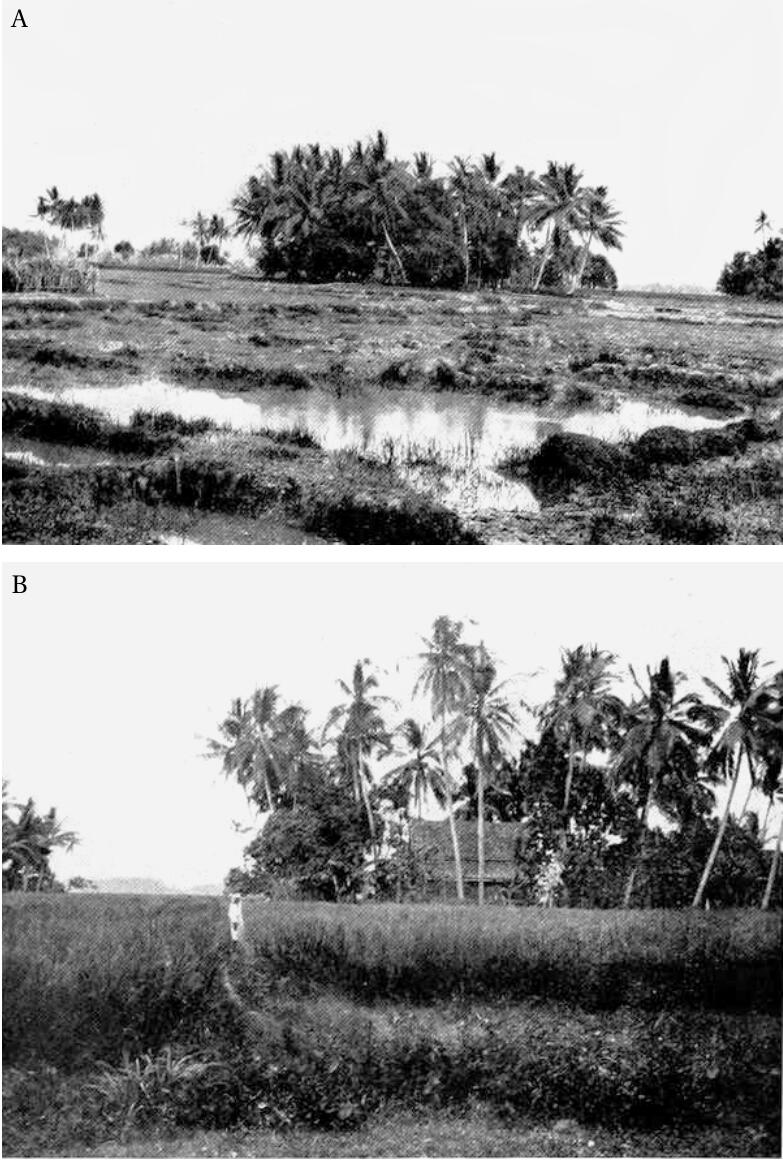

About 10 miles south-east of the Krian fields, the main range of the Peninsula is cleft by a valley leading to what is locally known as the Bukit Gantang Pass. (Bukit in Malay means a hill or mountain). The valley runs in some 5 miles, and its mouth, 2 miles wide, has Chankat Jering and Bukit Tebok on the north and south sides, respectively. From side to side, from end to end, the valley is a sea of padi, in which are studded Malay kampongs, like the “islands” of an archipelago (Figure 19.3). There is a considerable Malay population among the hills and on the “islands.”

| 19.5 |

The health of the children |

An examination of the children living at the foot of the hills showed that they were suffering severely from malaria.

In thinking over the idea of excluding certain species by altering the composition of the water, it occurred to me that, if an experiment were to be carried out, it would be best to avoid housing the coolies near the foot of the hills and sides of the ravines. Where A. maculatus were most likely to breed, would be the places to avoid in housing the coolies; and if an island in the middle of the padi could be made, there the coolies would enjoy the best health.

Having ascertained that the children on the edge of the hills were very unhealthy, I at once realised that in this valley the conditions of the experiment I had thought of were actually to be found on the most magnificent scale. The valley being 2 miles wide, the possibility of mosquitoes flying from the sides to the centre of it in such numbers as to carry malaria was excluded. It remained, therefore, to ascertain the percentage of children infected on both sides of the valley and in the centre, and to determine the species of the anophelines. Starting at Chankat Jering the Malay schools were examined.

At Chankat Jering fifty-one children were examined, of whom twenty-two (or 43%) had enlarged spleens. Two miles farther up towards the Pass, Jelutong school was examined. Of the thirty-nine children, seventeen (or 43%) had enlarged spleens, and several others had fever at the time of the examination without having enlargement of the spleen. Still nearer the Pass, Bukit Gantang school was found to contain fifty children, of whom twenty-five (or 50%) had enlarged spleens.

Thus, out of 140 children living at the foot of the hills and on the edge of the padi, no fewer than sixty-four (or 45.7%) had enlarged spleen, strong evidence of the prevalence of malaria. While at Simpang, 2 miles from Chankat Jering, out of thirty-three children examined at the school only three (or 8.9%) had enlarged spleens, showing that as we passed from the hills malaria was less severe.

I next examined the Bendang Siam school in the middle of the valley on the road running south towards Bukit Tebok. On this road, in the 2 miles where it runs through the padi swamps, there are no fewer than ten bridges, each indicating a small stream running down the valley. In the school of thirty-one children, nineteen (or 61%) had enlarged spleens. There were sixty-two on the register, but, as examination was made at the time of the fruit season, the attendance at the school was then about sixteen daily, and three visits had to be paid before the thirty-one children were obtained for examination.

In order to broaden the basis of the observation, and at the same time to obviate error due to the attendance of children from the south side of the valley, I examined fifty children in the houses of the “islands.” I was accompanied and assisted in this by Dr. Bryce Orme of Taiping, and we spent the best part of a day in going through the valley, which consisted of patches of dry land and of padi swamp irregularly mixed together. On the dry patches the Malay plants his house and his trees, and in the swamp grows his padi. Of the fifty children in the “islands,” eleven, or 22%, had enlarged spleens. Only one case of fever was found among the fifty children, and the inhabitants insisted that fever did not trouble them. The children found in the houses were mostly younger than those at school. It was thus obvious that both at the sides and in the centre of the valley malaria was present in serious amount among the children; but that the adults, presumably from having had the disease during childhood, were now immune, and consequently regarded the locality as healthy.

Apart from the evidence of the children, the history of the making of the railway, which runs over the pass, was one of severe malaria, especially at Ayer Kuning and Bukit Gantang, where large cuttings had been made.

I may remark here that the spleen rates of Malay children in their kampongs is not comparable with that of Tamil immigrants on an estate, since among the latter the non-immune new arrivals of all ages up to ten form a larger proportion of the total population than do the new born of the Malays. While a number of the Malays in the higher ages will already have acquired immunity, and lost the enlargement of the spleen, the Tamils, at all ages, will still be suffering from the disease.

Places newly populated by an immigrant coolie population showing a spleen rate of 100 may really differ considerably in the amount of malaria present.

| 19.6 |

Anophelines of Bukit Gantang valley |

During the four days (16th to 19th November, 1909), twenty-six adult anophelines were taken in the houses of the “islands,” or Kampong Paya and Bendang Siam, as the places are locally known. The species distribution is listed in Table 19.2.

| Species | Number |

| A. rossi | 10 |

| A. aconitus | 6 |

| A. barbirostris or A. sinensis | 9 |

| A. umbrosus | 1 |

The larvae of these mosquitoes were found breeding as follows (Table 19.3): Enormous numbers of A. barbirostris and A. sinensis were in the padi-fields. A. rossi were in pools near to the houses. A. aconitus was found breeding in a stream running through the padi swamps and in swampy grass, through which water was flowing slowly. Larvae of A. umbrosus were not found. In addition, one specimen of A. fuliginosus was hatched from a padi swamp about a mile in from the road.

In a set of coolie lines at Ayer Kuning, on the Chankat Jering side of the valley, three adult A. maculatus were caught in a few minutes. At Bukit Gantang village, fifteen adults were taken in houses, of which fourteen were A. rossi or A. sinensis and one A. aconitus. In a stream flowing down from the railway at Bukit Gantang, numerous larvae with simple unbranched frontal hairs were found in a backwater. These failed to hatch out.

On the Bukit Tebok side of the valley, in a house at the 11th mile, two adults were taken, one of which was A. barbirostris and the other A. fuliginosus. Larvae were taken in a spring at the edge of a swamp near this, with the characters of A. maculatus, but they failed to hatch out. While in a ravine running towards Bukit Tebok, numerous larvae belonging to the Myzorhynchus group, possibly either M. separatus or M. umbrosus, were found among the swampy grass. They, however, suffered, as did the other larvae, from the 200-mile journey to Klang, and failed to hatch out. A few miles further down this road, in the lines of a very unhealthy estate, ten A. maculatus were taken in half an hour. The estate is traversed by hill-streams.

| At the foot of the hills forming Bukit Gantang valley | In the rice fields of Bukit Gantang valley, “the islands” | In the Krian irrigation area | ||

| Malaria | + | + | – | |

| Species | ||||

| A. maculatus | + | – | – | |

| A. aconitus | + | + | – | |

| A. fuliginosus | + | + | – | |

| A. umbrosus | + | + | – | |

| A. barbirostris | + | + | + | |

| A. sinensis | + | + | + | |

| A. kochii | + | + | + | |

| A. rossi | + | + | + | |

Reviewing these facts, we may conclude that in the hill ravines and springs of Ayer Kuning and of the main range generally A. maculatus is acting as an efficient carrier of malaria, but the entire failure to take it in the “islands,” when it was so easily taken at the sides of the valley, warrants the conclusion that it does not spread far from the hills, and does not breed in the padi swamps. It is, however, evident that some of the other anophelines found there are carriers of malaria. A. rossi and A. barbirostris and A. sinensis can be excluded, since their presence in Krian caused no malaria. Suspicion must therefore rest on the other three, namely, A. umbrosus, A. fuliginosus, and A. aconitus.41 The first of these is the great carrier of the flat, undrained jungle land in Klang. It is easily seen and captured, as it is a large mosquito. As only one was taken, it is probably not the important carrier at Bukit Gantang rice fields. A. fuliginosus is closely related to A. maculatus, and A. aconitus is one of the small black-legged Myzomia group to which A. funesta (the African carrier) and A. culicifacies (the Indian carrier) belong. The time at my disposal did not permit me to complete the investigation of this point.

| 19.7 |

Conclusions from the observations of the Krian and Bukit Gantang irrigation padi fields |

Incomplete though they be, the investigations have established certain important points. These are:

- That the conversion of ravines into ordinary sawahs would not improve the health of a rubber estate.

- That these sawahs or padi swamps at the foot of hills or in ravines are extremely malarious, and that, although the adults appear to enjoy good health, the immunity from malaria which they possess has been acquired through their having suffered from malaria when children.

- That the estate in Negri Sembilan, which was supposed to become unhealthy on the introduction of the Tamil coolies, had always been unhealthy; and the adult Tamils had only suffered in the same way as the children of the Malays and other newcomers did.

- That vast areas may be put under wet padi or irrigated land without causing malaria was seen from Krian.

- That padi land at the foot of hills irrigated by the water from the hills is very malarious.

- That different groups of anophelines are found in (a) the water of hill-streams; (b) the water close to the foot of the hills; (c) the water at some distance from the hills.

- That on the difference of species of these anophelines depends the presence or absence of malaria.

It is not my purpose to record speculation here, but rather facts regarding malaria which have come to my notice during the past nine years. I cannot, however, pass from this subject without pointing out the great hope which these observations raise of dealing with malaria on new lines.

Hitherto the attitude towards the malaria of rice fields, and all rice fields were supposed to be malarious, has been that rice and malaria are inseparably connected. Rice, being the staple food of many millions in the tropics, must be grown. The choice appeared to be starvation or malaria; this is of course really no choice, since people must always run the risk of disease rather than starve.

The only attempts to destroy malaria where it was impossible to remove the breeding place entirely by destruction of the larvae, have been by the use of petroleum and by the use of certain poisons put into the water. The Italians favour an aniline dye. The cost of such applications, on the very large scale which would be required for rice fields, prohibit their use.

Very powerful larvacides are infusion of tobacco leaves, and the powdered flowers of the Dalmatian chrysanthemum. But here again expense prohibits their use. Daniels experimented with the tuba root—Derris eliptica—but even if it could be applied on a very extensive scale, it is doubtful if it is not too comprehensive a poison, since it poisons fish, and as Daniels says,42 “few forms of animal life are unaffected.” Such wholesale poisoning would probably interfere with the equilibrium of life in the padi-fields and produce consequences of an unwished-for character.

But in Krian we have seen that nature has carried out in the most successful way a method of altering the composition of the waters of the hills that the carriers of malaria no longer find it suitable for their existence, and malaria practically does not exist. I can imagine few greater benefits which the F.M.S. Government could confer on the Malay inhabitants than the discovery of the alteration which has occurred in the water, and its application to the numerous padi-fields of the Peninsula. It is not inconceivable that an industry might be found which required the maceration of a fibre, which, while changing the composition of the waters, might also provide the inhabitants with work. The culture of flax and hemp in Italy supplies a line upon which to work. A very large Malay population lives on the padi-fields of Perak, Negri Sembilan, and Pahang, who are now suffering from malaria in a severe form, unrecognised, it is true, since the children are the chief sufferers. This malaria must, in the course of generations, have left its stamp on the race, and possibly is responsible for the indolence of the Malay. Perhaps the Malay would become a less likeable character were he to acquire the energy of his Chinese competitor.

In the past the struggle was perhaps no uneven one; for what the Malay lacked in energy and capacity for constant work, he made up for by force of arms. In a sense, peace has disarmed but one of the competitors; and in the struggle for existence the Malay has now, unaided by the weapons of the past, to face an alien foe full of the energy and strength of the colder North.

If he is to survive in the struggle, it is essential that every obstacle be removed, and I can imagine no greater than malaria. Nor can I imagine how the West can more gloriously crown the benefits which it has heaped on the Malay in the past, than by the overthrow of the pestilence which saps the springs of his childhood life, and stamps the happy years of youth with pain and death.

| 19.8 |

The effect of drainage on different species of anophelines |

Now from the observation of species in Malaya and their behaviour to drainage, I would suggest it would be of practical importance to classify the anophelines of each country according to such behaviour.

We have seen that A. umbrosus is only to be found in a pool without a current, while a current of water means its destruction and disappearance. It can, however, breed in very weedy and obstructed ravine streams, as there the current is practically nil.

A. karwari, on the other hand, is a pool-breeder, which prefers a gentle stream of fresh water flowing through its pool. Such pools are commonly found in the springs at the foot of a hill, and this I consider is the normal habitat of A. karwari. A ravine stream, if much obstructed by weeds, has so little current that it closely simulates the normal habitat of A. karwari, and so we find this mosquito in weedy ravines. Remove the grass and the mosquito disappears. There is then too much current for it.

A. maculatus appears to prefer clear running water. There may be weeds, but they must not too seriously interfere with the free current of water. When disturbed it can leave the water, and it has powers of attaching itself to objects not possessed by pool-breeding larvae. These habits it doubtlessly has acquired; and it is perhaps due to evolution that the species of anophelines (both Myzomyia and Nyssorhynchus), which breed in streams, are generally smaller than the pool-breeders, since thereby they offer less surface to the current. We have seen that, since this mosquito prefers a current of water, an open drain is its normal habitat, and open drainage fails to eliminate it and the malaria it carries. Open drainage can only eradicate malaria carried by pool-breeders. Therefore in Malaya, whether a hill stream be clean weeded or grassy, malaria remains, only the species of anophelines carrying it differs.

A. rossi is at the opposite end of the scale from A. maculatus, and is a puddle-breeder. Since it is always found near to human habitations, the presumption is that it prefers pools soiled to some extent by human sewage. (Culex fatigans can breed in pure sewage, such as is found under a Malay house). On some estates, both on the hill and the flat land, this mosquito cannot be found. It, therefore, does disappear with thorough open drainage, although [it is] common enough in Klang town.

| Breeding place | Condition | Mosquito | Carrier in nature | Effect of weeding and drainage | |

| on mosquitoes | on malaria | ||||

| hill stream | free from grass | A. maculatus | yes | nil | nil |

| grassy | A. maculatus | " | " | " | |

| A. karwari | " | disappears | " a | ||

| choked with grass | A. umbrosus | " | " | " b | |

| springs and hill-foot swamps | grassy | A. karwari | yes | disappears | disappearsc |

| A. umbrosus | … | … | … d | ||

| A. fuliginosus | ? e | " | … | ||

| A. kochii | no | " | … f | ||

| A. barbirostris | " | " | … f | ||

| A. sinensis | " | " | … f | ||

| pools | not polluted, grassy | A. kochii | no | disappears | … g |

| A. barbirostris | " | " | … g | ||

| A. sinensis | " | " | … g | ||

| A. separatus | " | " | … g | ||

| A. rossi | " | " | … g | ||

| polluted | A. rossi | " | " | … g | |

- a

- because A. maculatus remains

- b

- because A. umbrosus [sic], which had been driven out, reappears. (Watson probably intended to say that A. maculatus reappears—M.P.)

- c

- Upkeep of drainage does not require to be very perfect [sic]

- d

- The dots in this table row seem erroneous—A. umbrosus is a major carrier, and the effect of drainage on this species is a major subject of this book—but they do appear in the original (M.P.)

- e

- There is evidence now (1920) that A. fuliginosus is not an important carrier of malaria, if it carries at all.

- f

- Upkeep must be perfect to eliminate these mosquitoes.

- g

- Surface drainage and upkeep must be perfect to eliminate these mosquitoes. Fortunately they do not carry malaria.

We have thus a series of waters differing in quality and rate of current. Each water has its peculiar mosquito inhabitants, which have a limited range of waters in which they can breed. On whether the mosquito carries malaria or not, and on the ease or difficulty of eliminating the insect by drainage, depend the amount of malaria in a country, and the ease or difficulty of combating it.

We see that in Malayan hill land, as long as there is an open system of drainage, malaria must remain, and in these hill lands malaria is as intense as anywhere in Africa. On the other hand, by good fortune, A. rossi—which only perfect surface drainage can abolish—does not carry malaria; and hence, as Daniels points out, Malayan towns do not suffer from malaria so much as African towns, where A. costalis, a mosquito with breeding habits similar to A. rossi, carries the disease. Consequently, although A. costalis can be destroyed by open drainage, to eradicate malaria in Africa would require a more thorough drainage and upkeep of drainage, than is necessary on the flat land of Malaya43 where mosquitoes like A. karwari and A. umbrosus are the carriers.

Finally, I would urge that our knowledge of the prevention of malaria would be materially advanced if more attention were paid to the places where malaria does not exist. A truer idea of the part played by anophelines will thereby be obtained, and a less pessimistic view be taken than is often the case.