| 26 |

The malaria of Kuala Lumpur |

Measures taken to bring about its abatement, showing the failure of empiricism and the success of a scheme based on the findings of entomological research. By Dr. A. R. Wellington, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., D.P.H., D.T.M. and H. Cantab., Senior Health Officer, F.M.S.

| 26.1 |

Introduction |

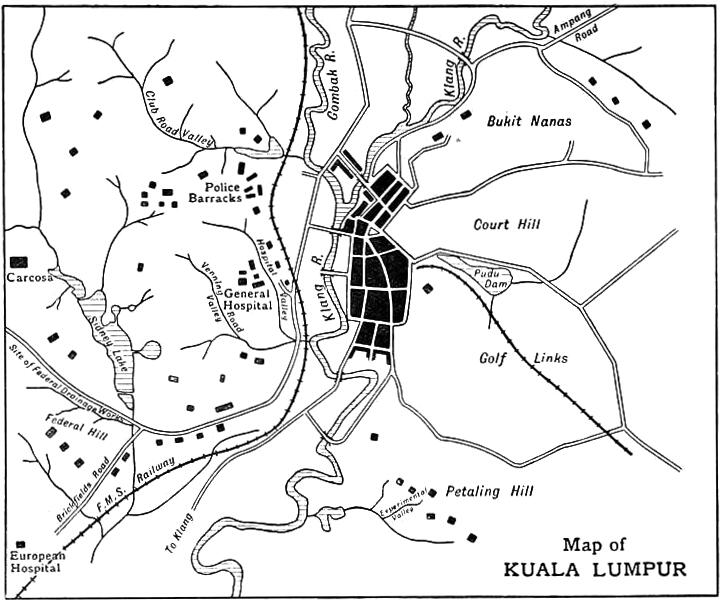

The town of Kuala Lumpur is situated on the Klang River, near the centre of the State of Selangor. It is a double capital, being the capital of the State and the capital of the Federation, and it is the headquarters of both the State Government and the Federal Government.

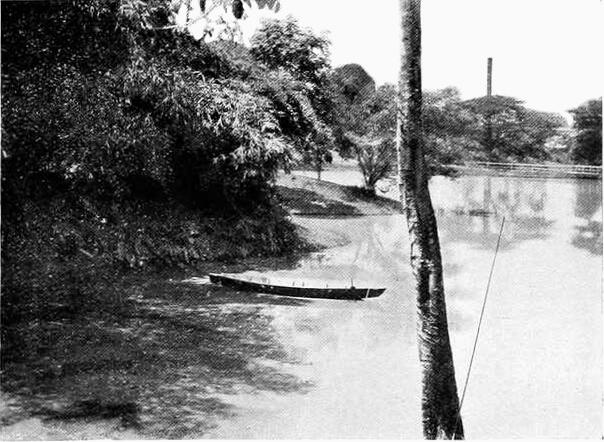

The whole township has an area of about twenty square miles. The town is bounded roughly by a circle, having at its centre the junction of the Klang and Gombak rivers (see Figure 26.1). The Klang makes, with the Gombak and its tributary the Batu, the figure of a Y, which divides the town into three approximately equal portions. The western portion, which is the European residential reserve, is made up of hills and ravines. The northern portion is flat. The eastern portion is flat in its northern half, hilly in southern half, except for a strip 60 chains long and 20 chains wide by the side of the river. This strip constitutes the business area of the town.

The population, which was 38,459 in 1905, is now (1920) 67,930. In 1905 most of the European officials were housed on the hills in the European residential reserve. The sides of the hills were for the most part covered with jungle, and the inverts of the valleys were jungle-covered swamps. The unofficial Europeans occupied houses on the flat to the east of the Klang River. They were isolated houses in their own compounds. The business area, in which three-fourths of the total population resided, was closely built upon.

| 26.2 |

Distribution of Malaria previous to 1906 |

Dr. Fletcher, in his report dated 30th July 1907, states as follows:

Until the end of 1906, malaria among the inmates of the European quarters was almost unknown, except in a few instances, and in these it could generally be proved that the disease had been contracted elsewhere. In those cases in which malaria was thus imported it never spread; no other inmates became infected. From this it may reasonably be inferred that no mosquitoes were present which were capable of carrying the infection. Until September 1906, I had not seen a case of malaria in a European house in which the probability of infection in another district could be excluded. Dr. Travers, whose experience in Kuala Lumpur extends over a period of twelve years, states that until this year he had not seen malaria among the European women and children of Kuala Lumpur, though cases have occurred among the men whose duties take them outside the town.

Malaria is endemic amongst that portion of the population which resides along the banks of the river, or near the swamps which border it.

Since 1903, the blood of all patients suffering from fever has, when practicable, been examined. Any figures, therefore, quoted hereafter refer only to cases which have been proved to be malarial by the demonstration of the parasite. During 1906, malaria parasites were found in sixty-six cases from Kuala Lumpur. Nearly all the cases seen came from the endemic area, only three occurring in European houses, and these during the last quarter of the year.

Dr. M’Closky, who had had twelve years’ experience of Kuala Lumpur, stated in August 1907: “I saw my first case of malaria in a European, contracted in Kuala Lumpur, only last month.”

There can be no doubt that up till 1906 malaria was confined to the areas which bordered on the river, and the hills were free.

| 26.3 |

Outbreak of malaria in the hill land, west of river |

Early in 1906, the jungle-covered swamp at the foot of Federal Hill was cleared, and an attempt made to dry the area by means of earth drains. The clearing was done by the Public Works Department, in order to improve the amenities of the locality prior to the erection of buildings on the high ground adjacent. About the same, time Dr. Fletcher had the blukar51 and scrub cleared from the swampy valley below the General Hospital. This was done to improve the appearance of the place, and to allow for better drainage.

During the year, the hospitals in Kuala Lumpur received many bad cases of malaria from the hill estates which were being started in the neighbourhood. The danger of opening up land had long been known to the pioneers of the country, who attributed the high malaria incidence and death rate to some miasma set free by disturbance of the soil.

Towards the end of the year, cases of malaria began to occur in Kuala Lumpur among the Europeans occupying the bungalows near the clearings, and among the patients and servants in the hospital. Previously both areas had been healthy. The incidence increased, and by the end of 1907, all the houses on Federal Hill and Carcosa Hill had cases of infection. Cases had also occurred in most of the houses near the hospital. The Police Barracks, which were on the hill opposite the hospital, had many cases.

Dr. Fletcher, in July 1907, sent in a report describing the outbreak. By means of a spot map he showed that the cases were coming from the neighbourhood of the clearings. He said:

The two main districts affected by the disease are (a) those parts near the swamps at the foot of Federal Hill; (b) the General Hospital and surroundings.

The cause of this outbreak must be some condition favourable to the breeding of the mosquitoes which convey the infection.

In each of the two neighbourhoods, the Federal Hill and the General Hospital, there is some low-lying swampy ground. A couple of years ago, these swamps were not drained, and in wet weather there was a considerable depth of water, but at that time there was no malaria in either neighbourhood.

About one and a half years ago, these swamps were drained, and subsequently malaria appeared in the houses near. The drains which were made are very irregular, and in places there are small pools and miniature dams, which probably make ideal breeding places for the noxious mosquitoes.

The remedy for the outbreak is efficient drainage. On that subject I am not qualified to advise, but would venture to suggest that the matter be laid before the Health Officer.

The following figures [see Table 26.1] show the actual numbers of the cases from the various districts which have come under my personal notice; and I would point out that they are, therefore, merely an indication of the distribution of malaria in Kuala Lumpur, and not the actual number of cases which have occurred. To obtain the latter, the figures given below would need to be multiplied by a factor, in most cases as large as 10, and in some, such as the Police Depot, not larger than 1.50.

| Location | Month | ||||||

| Jan. | Feb. | March | April | May | June | Total | |

| Brickfields Road | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 17 |

| Batu Road | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Ampang Road | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Police Depot | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 21 |

| High Street | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 19 |

| Central Workshops | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| Federal District | 2 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 25 |

| General Hospital | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| Other Districts | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 18 |

| Total | 22 | 23 | 20 | 12 | 25 | 30 | 132 |

Dr. M’Closky, the Acting State Surgeon, in forwarding the report to Government, wrote:

Dr. Fletcher rightly attributes this increase of malaria to some condition favourable to the breeding of mosquitoes which convey the infection, but I think there is another factor to be considered, namely, the source of infection of mosquitoes. This has [been] multiplied considerably by the large increase of malarial patients admitted to the General Hospital from the different estates.

The matter was referred to the Health Officer, Dr. Thornley, who wrote:

The method of draining valleys below Federal Hill is far from satisfactory, if not entirely wrong, as far as the attainment of the object of preventing breeding grounds for mosquitoes is concerned. The herring-bone system adopted leaves the ground between dry, but the drains themselves are grand breeding places. The drains below the European Hospital are lined with stones, and these result in the formation of small pools. The drains should be on the lines of Klang. Without money for upkeep it is a case of throwing money into swamps.

At Klang, Malcolm Watson used contour hill-foot drains to intercept the water from the hills.

| 26.4 |

The malarial committee, its investigations, discoveries, and recommendations |

In September 1907, the British Resident appointed a committee for the purpose of (a) examining the area complained of; (b) inquiring into the results arising from the present condition; (c) advising as to the methods to be employed for the improvement of each area, and to make an estimate of the cost in each case. The members of the Committee were—the Chairman of the Sanitary Board, Mr. E. S. Hose; the Health Officer, Dr. Thornley; the Medical Officer, Dr. Fletcher; and the Executive Engineer, Mr. J. E. Jackson.

The Committee started work by asking for the services of the Government Entomologist, Mr. C. H. Pratt, to make a thorough investigation into the areas complained of, for the purpose of ascertaining (a) the actual existence of malarial mosquitoes in the quarters infected, (d) the proportionate extent to which each area actually constitutes a breeding ground, for such mosquitoes.

The entomologist, during his investigations, discovered that larvae of Anopheles were “present in the streams flowing through the cleared portion of the valleys, but not in those parts where the streams remained covered with a thick growth of bushes. Even in the open portion Anopheles were not found where the stream flows swiftly between even banks, but wherever it had been scoured by flood and the stream had broadened out with retarded flow at the sides, there anopheline larvae were present in large numbers.”

Fletcher, who confirmed Pratt’s discovery, was quick to recognise the importance of it, and in his letter to the Chairman he stated: “These facts demonstrate the great danger of clearing jungle, unless it is possible at the same time to convert these streams into regular channels with clearly-cut sides, preferably of cement or brick.”

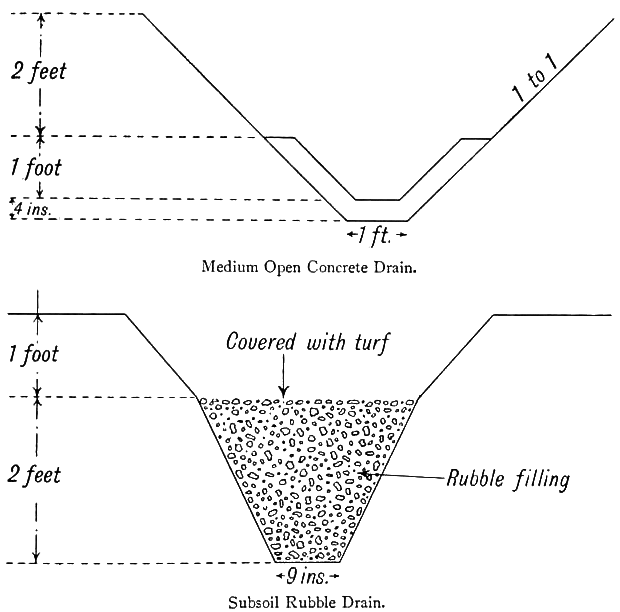

The Executive Engineer, Mr. J. E. Jackson, prepared surveys and estimates for a system of drainage in the areas referred to. The plans showed open brick drains running through the centre of the valleys, and subsidiary rubble drains covered with turf discharging into them (see Figure 26.3).

In February 1908 the Committee sent in a detailed report. The following extract from Paragraph 2 shows the importance they attached to Pratt and Fletcher’s discovery:

It is very noteworthy that Anopheles were found to be most prevalent in sluggish streams or earth drains where the thick overhanging undergrowth had been cleared away, as is the case, for instance, in the valleys on both sides of Hospital Road below the General Hospital, and at the foot of Federal Hill, and in the low-lying land in the angle between Brickfields Road and Damansara Road. These facts demonstrate the great danger of clearing the jungle covering of streams unless it is possible at the same time to convert such streams into regular channels of a uniform and fairly steep gradient, with clearly-cut sides. The Committee do not, however, wish to underrate the value of clearing jungle, provided that efficient drainage is undertaken at the same time.

Plans of Mr. Jackson’s drains, namely, open brick and subsoil rubble, were put up. $27,585 were asked for.

In asking for upkeep, the Committee said, “We consider that it will be necessary to maintain an upkeep gang of ten men who should be constantly employed in keeping these drains free from obstruction and in good order after they have been made, and with this end in view we recommend an annual expenditure of $1500, to which should be added a further sum of $500 for current repairs to drains.”

| 26.5 |

Criticism of committee’s findings |

The findings of the Committee came in for a good deal of criticism. Pratt and Fletcher’s discovery and deductions drawn from it were so incompatible with the generally accepted ideas, and so contrary to the teaching of the day, that little credence was given to them.

In every country where mosquito control had been attempted, emphasis was laid on the importance of clearing up all scrub, undergrowth, and jungle near to habitations and in towns. Local medical men had always advocated similar measures.

In Klang and Port Swettenham jungle clearing had been used with success, and to most there seemed to be no reason why the opposite should be the case in Kuala Lumpur.

That Anopheles carried malaria was known to all the local medical men, but the fact that there were a dozen or more species of anophelines in Malaya, and that some were carriers and others were not, was known to two or three only, and their knowledge of the subject was very limited. Practically nothing was known of the life-history of the different species, and it was not realised that conditions favourable for one might be unfavourable for another.

The anopheline which did the harm at Klang and Port Swettenham was A. umbrosus, a jungle breeder on flat lands; that which did the harm in Kuala Lumpur was A. maculatus,52 which breeds in the open on hilly lands.

In due time the report was submitted to the High Commissioner for his consideration. The High Commissioner, who paid a visit of inspection to the areas in question, was not convinced that the clearing had had any connection with the outbreak. He pointed out that there were cleared valleys of a similar nature in Singapore, and that they were free from malaria. He disallowed certain of the open brick or concrete drains and substituted rubble drains.

The sum asked for by the Committee was $27,585, the sum sanctioned was $10,320. Nothing was allowed for upkeep.

| 26.6 |

First attempt on part of Public Works Department to exterminate malaria by drainage |

The European residential area was on State land, and the task of ridding it of anopheline breeding-grounds was entrusted to the State P.W.D. to carry out in 1908.

It does not seem to have been realised that the problem was chiefly an entomological one, and that the engineering works necessary were only a means to an entomological end. The end aimed at was the rendering of certain areas impossible for mosquito propagation, and no system of drainage, however satisfactory, from an engineering point of view, was of the slightest use if that end were not attained.

Also it seems to have been forgotten that the extermination of any animal from an area where it is prevalent is rarely possible, unless the exterminators possess some knowledge of the animal and its habits, and that the chances of success are infinitesimal when the hunter cannot recognise the animal when he sees it. Mosquitoes are animals, and the above applies to anti-mosquito schemes.

With only one-third of the sum deemed necessary by the Committee, the Public Works Department had no chance of success even had they gone to work in the best possible way. They did not, however, attack the problem in the proper manner, and it is probable that, had the full sum been voted, the result would still have been a failure.

The engineers had never made a study of mosquitoes, and they could not spot an anopheline larva when they saw one. Being unfamiliar with the appearance of the larvae, they were unable to find out for themselves which were the dangerous areas and which were not. They could not tell, therefore, where to begin. The index of success was the absence of larvae from areas which, before treatment, contained them. They could not check their results, and they therefore did not know where to end. As they knew nothing of the mosquitoes they wanted to get rid of, it was clearly a case for cooperation with those who did know. Cooperation was not invited.

In direct opposition to the recommendations of the Committee, the valleys were cleared without being efficiently drained. Dr. Thornley had advocated drainage according to the Klang system, that is to say, contour hill-foot drains to intercept the water before it got to the swamps. His advice was not followed, and straight tap drains were put in instead. These drains only dried the ground within a few feet of them; the intervening spaces remained wet.

The subsoil rubble drains recommended by the Committee were not put in; open rubble drains were used instead. These soon became choked with silt. When all the money had been expended, the valleys were only half done. No provision having been allowed for upkeep, the drains when finished were left to take care of themselves.

| 26.7 |

Investigations by the Health Officer, and his findings |

In the middle of 1909, malaria in the European quarter was as bad as ever, if not worse, and it was evident that the measures taken had not been successful.

In an endeavour to arrive at the cause of failure, the writer, who had succeeded Dr. Thornley as Health Officer, made a personal survey of every valley in Kuala Lumpur from top to bottom, through cleared portions as well as through those still covered by jungle. Every stream, pool, or collection of water met with was searched for anopheline larvae. Those caught were bred out and identified.

No larvae were found in the jungle-covered portions of the valleys, though water was plentiful and a careful search was made. In the cleared portions they were easily found. There were many cases where larvae were plentiful right up to the edge of a clearing, but absent from the jungle-covered pools a few feet away. Pratt and Fletcher’s observations were thus confirmed.

In the valleys which had been treated by the Public Works Department, larvae were plentiful. They were particularly numerous in the spring water which trickled over the surface of the rubble drains. Not having been covered with turf (as recommended by the Committee), or otherwise protected, the spaces between the stones had become blocked by mud and silt, and the water which should have percolated through the rubble flowed over the top. In some valleys where concrete drains had been constructed, the only place where one could walk dry-shod was the top of the drain itself; everywhere else was like a sponge, and among the thousands of pools existing it was not difficult to find larvae.

A. maculatus and A. karwari were the species most common in the spring water which oozed from the bases of the hills. The smaller the pool the more likely it was to contain larvae; even the scrapings from the surface of wet sand showed them. Running spring water contained them.

A. rossi53 and A. kochii were found in dirty water such as is contained in buffalo wallows, wheel tracks, and drains contaminated by sewage. A. barbirostris and A. sinensis were met with at the edges of larger pools and ponds, especially where those edges were grassy or grass appeared above the surface. They were also found among floating debris. A. umbrosus larvae were not met with.

After the valleys had been done the flats were searched, a report accompanied by a spot map was submitted to the Principal Medical Officer. On the map fifty anopheline breeding places were shown. Attention was drawn to the fact that water in cleared valleys harboured anopheline larvae, while water in jungle-covered valleys did not.

Malcolm Watson had demonstrated that A. umbrosus and maculatus were carriers; nothing was known concerning the carrying properties of the other species. Watson had also shown that umbrosus is a jungle breeder, and that it disappears in clearing. The cause of the fever could not be A. umbrosus, for that species was conspicuous by its absence; besides, the clearing of jungle would have lessened the amount of malaria, whereas it seemed certain that it had had the opposite effect.

A. maculatus, the only other carrier known, was found breeding freely in the open valleys but not in those covered by jungle. The houses close to jungle-covered valleys had no fever, those near cleared valleys had. The obvious inference was that the clearing of the valleys had created conditions favourable for the propagation of maculatus, that the maculatus population had therefore increased, and the increased number of carriers had raised the incidence rate among those living in the neighbourhood.

Pratt and Fletcher’s theory was correct, and the warning issued by the Committee was sound. In the execution of the anti-mosquito works, that warning had been ignored. The valleys were felled and cleared, but not efficiently drained, and an increase instead of a decrease in the number of breeding places resulted.

The following is an extract from the Health Officer’s annual report of 1910:

It was noted that, where the valleys had been cleared of jungle and blukar, larvae of the malaria-carrying anopheline A. maculatus were found without difficulty in the clear water which had issued from the springs at the hill-foot. In the valleys covered by blukar or jungle, where the water (of which there was plenty) was coloured with vegetable matter, not a single anopheline larva was found.

This experience agrees with that of Pratt and Fletcher in 1907. As malaria-carrying anophelines breed in cleared valleys and shun those covered with blukar, the obvious inference is that the clearing of valleys will be followed by an outbreak of malaria if foci of infection be present and the valleys are left inefficiently drained.

The findings of the Health Officer were not generally accepted, and even the medical officers remained unconvinced of the danger of clearing valleys. The subject was so important that independent action should have been taken to prove or disprove the theory, but nothing was done.

| 26.8 |

Experimental drainage works on Petaling Hill |

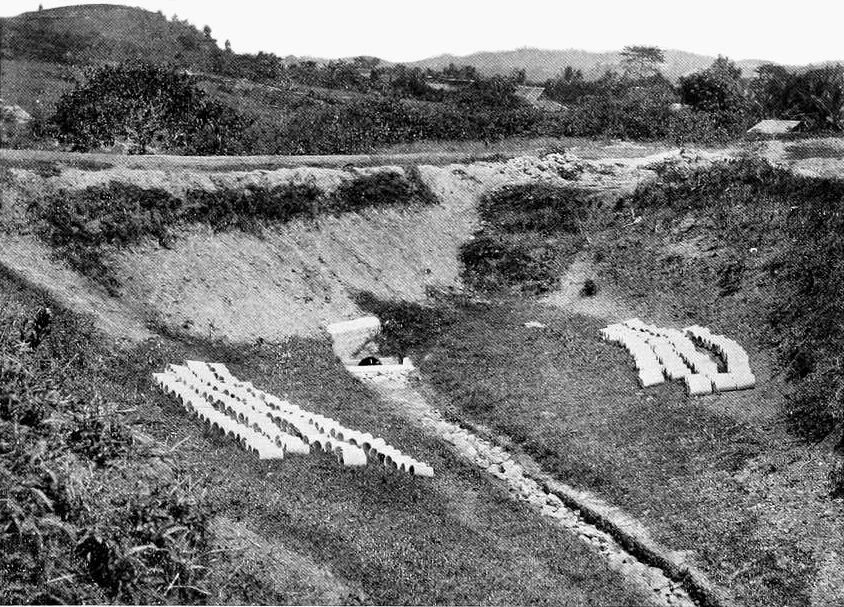

The investigations of the Health Officer commenced about the middle of 1909, and the report on the anopheline survey was delivered to the Principal Medical Officer in April 1910. During the interval, notifications of malaria were constantly being received. Each case was gone into as thoroughly as time permitted. At the end of 1909, a European who lived on Petaling Hill, a new residential area not included in the Committee’s report, wrote in complaining that all his household had been down with fever, for which he blamed the ravines in front of his quarters in Belfield Road. The ravines contained scrub and blukar, but there were open spaces in them. The inverts were wet and swampy (Figure 26.2). An anopheline survey by the Health Officer showed the presence of the fever-carriers A. maculatus in the open areas. The findings were reported to Government and drainage recommended, a concrete drain to run down the centre, and contour open earth-drains at bottom of slopes to connect at intervals with centre drain.

The State Engineer fixed upon one of these valleys as a suitable place for experimentation in drainage, and trials were begun. The valley was cleared of scrub, and drainage on the herring-bone system tried. The central drain was an earth channel, having at its invert concrete half-pipes roofed with flat, perforated, concrete slabs; the rest of the channel was filled with broken stone. Except that the pipes were different, the drains were similar to those used with success at Panama.

The subsidiary drains or ribs of the herring-bone were earth channels filled with broken stone (Figure 26.4). The experiment was watched by the Health Officer, who checked the results by frequent mosquito surveys.

The concrete pipes worked well. The rubble drains, when new, dried the soil for a couple of feet on either side; beyond that they had no influence, and the ground remained wet and sloppy, and in the small pools larvae continued to develop. In a short time, the interstices of the rubble drains became choked with mud and silt, and the drains ceased to convey water. The choked drains were taken up and relaid. To dry the spaces between, some contour or intercepting drains were constructed at the hill-foot. The contour arrangement was a great improvement on the simple herring-bone, and for a time the valley was dry. In a month, however, the rubble drains had again become choked, and it was decided to abandon them.

In February 1910, Dr. Malcolm Watson, at a meeting of the British Medical Association in Kuala Lumpur, read an interesting paper on malaria prevention. He described what had been done in Malaya and the results. He pointed out the difficulties he had encountered in hill lands, and he advocated a system of contour hill-foot drainage by means of clay pipes laid underground. At that time clay pipes were not to be had in Malaya. The local potters made flowerpots and jars, but they had never tried their hands at pipes. Dr. Watson pointed out that there was no reason why these pipes could not be turned out very cheaply, and he showed specimens which he had had made locally. He described a system of clay-pipe drainage, which he proposed to use on certain hill estates in the highly malarious Batu Tiga district.

In July, Dr. Watson paid a visit to the experimental drain at Petaling Hill, and offered some friendly criticism. He considered that the main drain, the concrete pipe overlaid with stone, was performing its task satisfactorily, but that it was unnecessarily expensive. The rubble drains he condemned. A trial of clay pipes was recommended, and as none could be obtained in Kuala Lumpur, he offered to provide a pattern which the local potters could copy. Mr. R. D. Jackson, who had newly taken over the anti-malarial drainage of State lands in Kuala Lumpur, took action on the lines suggested and arranged for pipes to be made. The potters, seeing there was money in it, commenced making pipes on their own. This was the beginning of an industry which has so developed that there are now half a dozen potteries which manufacture clay pipes for anti-malarial purposes.

The rubble drains were all taken up and replaced by clay pipes overlaid with broken stone, a system similar to that which had proved successful in Panama (Figure 26.5). The valley was dried, and remained dry for a year or more. Upkeep was necessary.

| 26.9 |

Second attempt by Public Works Department to exterminate malaria by drainage |

Sometime about the middle of the year 1910, a sum was voted for the purpose of remedying the defects of the 1908 drainage system, and for certain extensions. The work was again entrusted to the Public Works Department to carry out. On this occasion, both Federal and State lands were concerned. Operations on Federal land were allotted to a Federal engineer, that on State land to a State engineer. The two worked independently.

Plans for the State land were submitted to the Health Officer, who passed them on condition that they were not to be considered final, but that any deviation found necessary during the progress of the work would be carried out. The Health Officer asked for the drainage of jungle-covered valleys and the felling to proceed side by side. This was rejected as impracticable.

Plans for the Federal land were not submitted.

Work on State land commenced in July. The writer made frequent mosquito surveys during the progress of the work, and communicated the results to the Executive Engineer.

Contour drainage had been repeatedly advocated by the writer, but up to this time no engineer had consented to give it a trial. In this month, a trial on a small scale was made, both in Belfield Road experimental area and in Club Road Valley (Figure 26.8). An entry in the Health Officer’s diary, dated 28th July, says: “Inspected Belfield Road and Club Road. I am glad to see the P.W.D. are trying contour drains at last, though they are not making them deep enough.” That they were only half convinced is shown by the following extract from the same diary: “Inspected anti-malarial drains in Club Road. The P.W.D. are putting in straight drains where they ought to put in contour drains. The scheme will be a failure unless the P.W.D. use common sense.” Common sense eventually prevailed, for the diary entry of 28th September says: “Inspected Club Road Valley. The contour drains have done the trick and the valley is perfectly dry.” Leaving out the experimental one in Belfield Road, this is the first instance of a valley having been drained to the satisfaction of the Health Officer.

Other valleys received attention, but the work there was not so thorough, and when operations ceased, there still remained sufficient breeding grounds to supply all the carriers necessary for maintaining the high malarial rate existing in the neighbourhood. Much good work had been done, but it had not gone far enough.

While the State authorities were engaged with the works on State land, a Federal engineer was dealing with the Federal area. The Health Officer offered advice, but it was not taken. Watch was kept, and the various collections of water were frequently examined for the presence of larvae.

The concrete blocks intended for the open drains were cast on the spot. Unfortunately, the ground chosen for the casting operations was wet and spongy, and many small pools formed. The pools became populated with A. maculatus larvae. At the end of 1910, so much breeding was going on that an increase of malaria seemed inevitable. Warning was given, but no action was taken, and the breeding continued.

| 26.9.1 |

Formation of Health Branch of the Medical Department |

In January 1911, the Health Branch of the Medical Department came into existence, and the writer was transferred to Taiping in the State of Perak as Health Officer, Perak North. Taiping is situated on the flat at the base of the hills. The European quarter is on that side of the town next to the hills. Until the previous year, this quarter had been healthy, but it was now malarious. The malaria followed the clearing of the hill land for rubber growing. Investigations were made, and it was found that, as in Kuala Lumpur, the carriers were coming from the cleared valleys. All the valleys were searched. In those covered with jungle, no larvae were found; in those which had been cleared, A. maculatus breeding grounds were found in plenty. A mosquito survey of the whole town was made, and a spot map prepared. Only near the bases of the hills were carriers found. The European area suffered, but there was little malaria in the rest of the town.

Malarious hill estates in the neighbourhood were investigated, and in each case A. maculatus breeding grounds were found in the cleared valleys and not in the jungle-covered ones. Pratt and Fletcher’s theory was true for the hill lands of Perak.

| 26.10 |

Continuance of malaria |

Malaria in Kuala Lumpur in 1911, instead of declining, increased. The conditions of the valleys at the beginning of the year were as follows:

- Club Road Valley was dry except at its mouth, where there was a large pond (Figure 26.9). The pond did not furnish carriers, and it therefore had no influence on the malaria.

- Bluff Road Valley and Hospital Valley had not been completely dried, and there were still maculatus breeding grounds, especially in the upper reaches.

- Venning Road Valley was not satisfactory, and breeding grounds existed.

- In the gardens there were still many dangerous places.

- A. maculatus larvae were easily found near the Federal Anti-mosquito Works.

In fairness to the engineers it must be stated that the valleys which had been treated were not the only ones which contained anopheline breeding grounds. Owing to the general disbelief in the danger of clearing valleys, no action had been taken to prevent further clearing. New valleys had been cleared by the Agricultural Department and by others and new breeding-grounds had been created. These furnished their share of mosquitoes.

Every house on Carcosa Hill and Federal Hill had cases. All were within easy flying distance of the Federal Anti-mosquito Works.

| 26.11 |

Confirmation of Watson’s discovery that A. maculatus is a carrier |

On June the 8th Dr. Stanton, the Government Bacteriologist, demonstrated the presence of zygotes in the stomach wall of A. maculatus taken in a house in Brickfields Road, close to the Federal Anti-mosquito Works. On June the 28th, in conjunction with Dr. Watson, specimens of this mosquito were taken in coolie lines on a hilly estate in the notoriously malarious Batu Tiga district and sporozoites were demonstrated in the salivary glands. Watson’s discovery, made in 1906, that A. maculatus is a carrier in nature, was thus confirmed. Dr. Stanton says:

The number of A. maculatus taken in the lines and the readiness with which parasites were demonstrated in them at a time when I was informed the estate was comparatively free of malaria, and the absence of parasites in other species of anophelines examined, show the great importance of this mosquito in malaria transmission in hill areas.

It is a pity that Pratt and Fletcher’s theory was not tested at this stage. The question, however, was not taken up, and the theory remained discredited until 1915 when Strickland published a paper confirming it. Clearing went on steadily in Kuala Lumpur. An extract from Dr. Gerrard’s health report of 1911 says:

During the year much jungle and undergrowth was cleared, and many subsoil drains laid. In spite of this malaria has increased. … The anophelines of the environs of Kuala Lumpur are being worked out by Dr. Stanton of the Institute of Medical Research, and maps showing where larvae are found are nearing completion.

The fact that there was a recent anopheline survey map of Kuala Lumpur already in existence seems to have been overlooked, at any rate no use was made of it.

| 26.12 |

Formation of Malaria Advisory Board |

Dr. Charles Lane Sansom was appointed Principal Medical Officer, F.M.S., in January 1911.

On his arrival he found that the medical problem which most required attention was malaria and its prevention. The position in Kuala Lumpur was far from satisfactory. The subject had been engaging the attention of the authorities for four years, yet in spite of the efforts made, malaria was on the increase. Dr. Sansom made investigations and came to the conclusion that the reasons for failure to reduce malaria lay in division of responsibility, lack of thoroughness, and unsuitable methods resulting in bad drainage. The works had been controlled by various State and Federal authorities, each of whom proceeded independently.

In August Dr. Sansom wrote in to Government and pointed out “that the suppression of malaria in these States is not such a simple matter as it is described in the works of Ross and Boyce.” Because of the difficulties which had to be overcome he recommended the appointment of a standing Committee to—

- (a)Collect information and evidence with regard to the incidence of malaria.

- (b)Select the most appropriate schemes which could be used in various parts of the States, and advise Government as to how they should be carried into effect.

- (c)Issue instructions as to details, control, and upkeep of anti-malarial works.

- (d)Diffuse information.

- (e)Undertake any other duties which in the opinion of the Chief Secretary would be likely to prevent malaria.

The Committee recommended was—

- The Principal Medical Officer.

- Dr. Stanton, “to keep members in touch with research work here and elsewhere.”

- Dr. Malcolm Watson “as the medical representative who had had much practical experience.”

- One or two prominent planters.

- A district officer who had had experience in Sanitary Board work.

- An engineer skilled in drainage work.

According to Sansom,

Such a Committee would inspire public confidence in the first place and therefore there would be less resistance to any measures which might have to be enforced. The Government would be advised as to the best means which could be adopted to control the disease, and if all contemplated schemes are submitted to the Committee, not only would uniformity result, but expenditure on useless fads and theories be prevented.

Government accepted the recommendations, and the Malaria Advisory Board was formed. The composition of the Board was—E. L. Brockman, Esq., C.M.G., Chief Secretary, President; Dr. C. L. Sansom, Principal Medical Officer, Vice-President; J. H. M. Robson, Esq.; Dr. Malcolm Watson; H. R. Quartley, Esq.; Dr. A. T. Stanton; F. D. Evans, Esq., Assistant Engineer, Public Works Department.

The Board met for the first time in November, and there was a second meeting in December. It was decided that the drainage of the European residential area should be completed under the instruction of the Board “to serve as an illustration of what could be done by this means to free an area of malaria.” It was decided to work on the following lines:

- All ravines to be cleared for 6 feet up the hill.

- Open earth channels to drain land previous to pipe laying.

- Subsoil contour pipe drains (clay pipes) to be placed at the foot of all slopes.

- The cement drains already in position to be left for the time as they might prove satisfactory.

- Mr. F. D. Evans to supervise the work.

| 26.13 |

Work commences under Malaria Advisory Board |

Mr. Evans, who was seconded from the Public Works Department and was appointed Executive Engineer to the Board, realising the vital importance of the mosquito side of the problem, early took up the study of the local anophelines. He was the first engineer in the F.M.S. who had ever bothered about them. He was thus able to check results and ensure that each section had been freed from breeding grounds before another was commenced.

Some idea of the incompleteness of previous works can be got from the minutes of the Board of 12th February 1912:

The Board is informed that every ravine head is left unfinished, thus creating typical mosquito breeding places for mosquitoes most dangerous to health. Additional drainage on Petaling Hill is approved. Undergrowth along drains in Federal Reserve to be cleared, and when drainage has been completed, jungle on both sides of the hill to be cleared. Additional work required in ravines between Club Road and Maxwell Road.

To subsoil the whole of the ravines west of the river was a big job, something like 50 miles of piping being necessary. The work was pushed on rapidly, but of course it took time to complete.

Experiments were made in draining, and it was early found that the rubble filling over pipes was not only unnecessary but harmful—better results could be got by protecting the pipes from silt with a layer of dried palm leaves and covering in the trench with earth. The same system had been used with success on Seafield Estate, which had been drained under the supervision of Dr. Watson.

The subsoil drains laid in the 1910 campaign were left until they showed signs of blockage, when they were taken up and replaced by others. By the end of 1913 there were practically none of the old type left.

| 26.14 |

European residential area cleared of malaria |

The results of the drainage wer most satisfactory, and in 1913 the European residential area for the first time in seven years was free from malaria, and it has remained free ever since.

For the first time in the history of Kuala Lumpur, anti-mosquito works had been carried out under the authority of a Board containing medical entomologists familiar with the mosquito it was desired to get rid of.

The success was due to the complete eradication of A. maculatus breeding grounds, brought about by a system of drainage specially designed to deal with the problem. Particular mention must be made of the excellent work done by Mr. F. D. Evans, the Board’s executive engineer. He was keenly interested in the subject, and he carried out the details of the scheme with such thoroughness and skill that no place was left suitable for A. maculatus to breed in. Strict attention to detail was absolutely essential, for with so efficient a carrier as A. maculatus, even small and insignificant-looking pools of water are sufficient to keep the disease smouldering.

Malaria not being a notifiable disease, the incidence figures are not available. Europeans, however, are never slow in complaining to the Health Officer when a case occurs in their households, and the fact that complaints which had been of almost daily occurrence in 1910 and 1911 ceased to be received after 1912 shows that malaria in the European residential area came to an end about that time.

| 26.15 |

Influence of drainage not confined to residential area |

The influence of the drainage operation was not confined to the European quarter; the shop house area of the town was within flying distance, and there is no doubt that it benefited. The malaria death rate for the whole town dropped from 9.87 in 1911 to 5.53 in 1912.

The report of the Health Officer (A. R. Wellington) for 1913 says:

The great drop in the death rate for this disease must be attributed to the extensive drainage operations which were undertaken by the Malaria Advisory Board to get rid of the breeding places of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Valleys which were teeming with maculatus larva, are now bone-dry.

The action taken by the Malaria Advisory Board in the area selected for demonstration purposes had been so successful that it was decided to extend operations and deal with other areas in the town where malaria was prevalent.

Table 26.2 shows the numbers of deaths among the residential population due to “fevers,” in most cases malarial, the fever death rate of the population, as well as the general death rate.

| Year | Populationa | Deaths from fever | General death rate (‰) | |

| Number | Rate (‰) | |||

| 1907 | 41,331 | 537 | 2.99 | 36.40 |

| 1908 | 42,775 | 423 | 9.88 | 41.19 |

| 1909 | 43,209 | 341 | 7.89 | 32.95 |

| 1910 | 45,642 | 486 | 10.64 | 33.15 |

| 1911 | 47,076 | 465 | 9.87 | 39.02 |

| 1912 | 48,508 | 266 | 5.53 | 37.00 |

| 1913 | 56,487 | 314 | 5.56 | 35.62 |

| 1914 | 58,107 | 361 | 6.21 | 35.88 |

| 1915 | 59,727 | 325 | 5.44 | 27.83 |

| 1916 | 61,443 | 408 | 6.64 | 27.73 |

| 1917 | 63,064 | 293 | 4.65 | 28.45 |

| 1918 | 64,686 | 393 | 6.08 | 38.34 |

| 1919 | 66,308 | 311 | 4.69 | 26.36 |

- a

- The census in 1921 shows the population to be 70,000.

The figures for the year previous to 1907 are too unreliable to be quoted, for, until that year, the importance of distinguishing between deaths due to diseases contracted in the town and those contracted outside was not generally realised, and the subject did not receive the attention it merited, either at the hands of the hospital authorities or the police, to whom deaths outside hospital were reported. The figures for any year are not strictly accurate, for often a native deliberately gives a fictitious address on entering hospital—they are, however, sufficiently accurate for general comparisons.

In 1918 a severe influenza epidemic spread over the whole country, and probably many of the deaths returned that year as due to fever were really influenza deaths.

| 26.16 |

Drop in death rate not due solely to Malaria Advisory Board |

The great drop in the general death rate from 39.02 in 1911 to 26.36 in 1919, that is, 12.66‰ population, must not be attributed solely to the action of the Malaria Advisory Board. The average fever death rate for 1908 to 1911, the period in which clearing of valleys was not followed by efficient drainage, was 9.57; that of 1912 to 1919, the period in which clearing was accompanied by efficient drainage, was 5.53, a drop of 4.04‰ only. (1918, being the influenza year, is not counted.)

Malaria, of course, has an influence on other diseases, and the drop in the fever death rate does not indicate the total improvement brought about by abatement of the disease. Again, the operations of the Malaria Advisory Board were not the only anti-malarial measures being carried out in the town. The Health Officer’s staff and the Sanitary Board staff had not been idle, and a considerable amount of oiling and minor works had been done.

It is not unfair to the Malaria Advisory Board to attribute half the total drop in the death rate to their operations and the other half to the improvement in the health conditions brought about by the Health Department of the Sanitary Board.

| 26.17 |

Pratt and Fletcher’s theory confirmed by Strickland |

In 1912, Dr. C. Strickland came to this country as Medical Entomologist to carry out research in connection with the biology of mosquitoes. In 1915, this officer published a paper giving the results of his research in hilly lands. His experiences coincided with those of Pratt, Fletcher, and Wellington, in that he found wooded valleys practically free of larvae of malaria-carrying anophelines, while cleared valleys contained them. He said that hilly land, provided the valley were left alone, was not malarious, and that hilly land with cleared valleys was. He advocated the non-clearing of valleys in the vicinity of habitations, and recommended that those cleared should be allowed to revert to their original state. The matter was taken up by the press and given full publicity. Pratt and Fletcher seem to have been forgotten, for their names were never mentioned. The theory was called “Strickland’s Theory,” and that is the name by which the public knows it today.

| 26.18 |

Malaria Advisory Board acknowledges danger of clearing valleys |

The Malaria Advisory Board now for the first time gave the theory serious attention, and apparently it became convinced of its truth, for in August 1916, in a circular issued from the Federal Secretariat setting forth the aims of the Board, the following statement occurs:

4. The Board aims at the extermination of Anopheles mosquitoes in all thickly populated centres, and wherever economically possible in rural areas, and wishes to effect a reduction in mosquitoes generally. The means to be adopted are (a) … (e) Non-disturbance and encouragement of dense natural growth in ravines and swamps where effective drainage is not carried out, and where the conditions are such that this course will result in preventing the formation of anopheline breeding places.

This, in other words, is the warning of the Malarial Committee issued in 1907, consequent on Pratt and Fletcher’s discovery. Nine years were allowed to elapse before the theory received formal recognition.

| 26.19 |

Summary of work done by Malaria Advisory Board |

At the end of 1917, the area maintained by the Malaria Advisory Board was 4500 acres (over 7 square miles). The drainage completed included 65 miles of subsoil piping, 81/2 miles of open masonry channels, and 12 miles of open earth channels.

The figures in Table 26.3, taken from the Board’s report for 1918, show the money expended in anti-malarial works in Kuala Lumpur.

| Year | Construction | Maintenance | Total |

| 1908-11 | $47,705 | $6,986 | $54,691 |

| 1912 | $37,526 | $5,559 | $43,085 |

| 1913 | $68,459 | $11,118 | $79,577 |

| 1914 | $22,314 | $11,156 | $33,470 |

| 1915 | $8,988 | $10,705 | $19,593 |

| 1916 | $23,054 | $10,487 | $33,541 |

| 1917 | $23,630 | $10,205 | $33,835 |

| 1908-17 | $183,971 | $59,230 | $243,201 |

How much of this would have been necessary, had Pratt and Fletcher’s theory received due recognition and the valleys been left in jungle, it is difficult to say. One thing, however, is certain, the valleys had either to be left absolutely alone or cleared completely and thoroughly drained, for where so efficient a carrier as A. maculatus is concerned, partial measures are inadmissible. To keep the valleys in such a town as Kuala Lumpur undisturbed, fencings and an efficient system of patrol are essential. Nothing short of this will prevent the Asiatic citizen from trespassing and interfering with the natural growth. Probably sooner or later, clearing would have been found necessary.

| 26.20 |

Conclusion |

The story of the rise and subsidence of malaria in the hill land of Kuala Lumpur has been told at some length, for it is of much interest.

There is no doubt that the clearing of the valleys started malaria in the European residential area, and increased the incidence and death rate in the town generally. The findings of Pratt, Fletcher, and Wellington showed the relative harmlessness of jungle-covered ravines, but those findings were disregarded.

From 1906 to 1911, the residential area became progressively more malarious, and the anti-malarial campaigns carried out by the Public Works Department did more harm than good. In 1912, a suitable system of drainage was laid down at considerable expense; the malaria disappeared from the hills, and the death rate in the town fell considerably.

Kuala Lumpur stands as an expensive warning against interference with jungle ravines in “Inland Hills,” unless provision has been made for draining those ravines bone-dry, and maintaining them in that condition. The lessons taught by the three anti-malarial campaigns (1908, 1910, and 1912) are:

- That anti-mosquito schemes cannot be a success unless framed and carried out under the supervision of those familiar with the habits and life-history of the species it is intended to get rid of.

- That a scheme suitable for the eradication of one species of mosquito is not necessarily suitable for another. The methods found successful in the case of A. umbrosus proved worse than useless in the case of A. maculatus. Schemes suitable in one country should not be slavishly followed in another where the mosquito fauna is different. A thorough mosquito survey is an essential preliminary to any scheme, and the scheme should be framed according to the mosquito findings.

- That a problem full of indeterminate elements is impossible of solution without trials and experiments; unforeseen difficulties are certain to arise in the course of the work, and allowance should be made for any deviation from the scheme which may prove necessary. In many cases the estimate of costs can only be a guess, and a scheme should not be allowed to fail for want of a little extra money.

- That in hill land, clearing of valleys, unless followed by efficient drainage, is dangerous, as it promotes facilities for the propagation of the dangerous carrier A. maculatus.

| 26.21 |

Note on Kuala Lumpur by Malcolm Watson |

To the interesting chapter written by Dr. Wellington, there is little to add, except on two points. By 1910, over three years had passed since the inception of the anti-malarial work in Kuala Lumpur; yet malaria was becoming more and more severe; mosquito control and malaria control had proved a complete failure. It was even said that a place once particularly free from malaria had become intensely malarious as a consequence of the anti-malarial campaign. Money had been spent on open drains, on rubble drains, on concrete drains, and subsoil drains—without success. Government now appeared to be disinclined to spend more money; possibly because it seemed like throwing good money after bad. In June 1910, at Dr. Travers’ suggestion, I gave a public lecture in Kuala Lumpur, and explained the problem. I urged the need for research, the creation of a Sanitary branch, and cooperation between all branches of the Department of Medicine, namely hospitals, research, and sanitation.

Throughout the remainder of 1910 and most of 1911, practically nothing was done in Kuala Lumpur. To me it was a period of anxiety. I had advised some estates to lay down a system of subsoil drainage to overcome A. maculatus, and some had agreed to do so. But it was hopeless to expect much progress throughout the country, when the Federal Capital was notorious as an anti-malaria failure. Indeed I feared that the failure in Kuala Lumpur might be to the Malay States what Mian Mir was to India. At Mian Mir, the Imperial Government of India and the Royal Society of England joined forces to eradicate malaria from the Cantonment. It is unnecessary here to go into details; but the experiment was a failure. Sir Ronald Ross [2] says of it: “In fact the whole affair was conducted on unpractical and unscientific lines. It proved nothing at all, and its only effect was to retard antimalaria work in that and other countries for years.”

For anything like that to occur in the Malay States, where so promising a start had been made ten years before, would indeed have been a disaster. Government, however, did not move for over a year; but on the formation of the Malaria Advisory Board at the end of 1911, I urged the importance of clearing away the malaria of Kuala Lumpur, as the first duty of the Government. The system I had devised for Seafield Estate was adopted, as is described in the Annual Medical Report for 1911; and its success is due to the careful way in which it was carried out by Mr. Evans, the Board’s engineer.

The only other point I propose to mention is the importance of continuous and ample malaria research. Our ignorance of the distribution of A. umbrosus has cost this country heavily both in money and in lives. I was familiar with the Coastal Plains and coastal Hills, with jungle and the jungle-loving A. umbrosus and A. aitkeni. Dr. Leicester had caught A. umbrosus in Kuala Lumpur; and some specimens of the mosquito had been taken by a gentleman in his house in Kuala Lumpur and given to me. I had known many curious instances of the appearance and disappearance of the insect. Sometimes enormous numbers would disappear in a few days. At times it is easily got: at other times not. Therefore I attached little or no importance to Mr. Pratt’s, Dr. Fletcher’s, and Dr. Wellington’s failure to find the insect in ravines.

These gentlemen, on the other hand, had no knowledge of the Coastal Plains and Coastal Hills, in which A. umbrosus abounds. Thus no one realised that the distribution of A. umbrosus was so peculiarly limited; and that Kuala Lumpur and Batu Tiga, which are only some ten miles apart, and apparently in similar hilly land, were in different zones; the ravines of one harbouring A. umbrosus, those of the other not; from a malarial point of view, a difference of first importance. Not suspecting the truth, I was greatly puzzled by many places, as I have described in Chapter 20; and it was not until Dr. Strickland informed me of his discovery of the absence of A. umbrosus from certain hills, and after my visits to Pahang and Batu Arang, that the truth seemed to be found; namely, that A. umbrosus was limited to the Coastal Hills, and did not spread to what may be called the “Inland Hills.” Had there been more research, in 1909, as Dr. Wellington suggests, the truth would have been discovered sooner: and in the extensive clearings subsequent to the Rubber Boom in 1910, many a ravine would have been left in jungle, to the great advantage of the public health. As it was, the importance of what had been discovered by Messrs. Pratt, Fletcher, and Wellington was not appreciated; the truth had to be rediscovered by Dr. Strickland. Even then Government was slow to believe it; and the treatment meted out to Dr. Strickland is a blot on the name of the administration of this country.

To sum it up, the administration in the past has not provided sufficient malarial research nor encouraged it; and for lack of knowledge, large sums have been wasted on badly designed or unnecessary work, progress has been spasmodic, and an enormous number of lives have been lost.