| 8 |

The malaria of the Coastal Plain and Anopheles umbrosus |

| 8.1 |

Different zones of land |

Perhaps the word “plain” is not altogether apt. If it conveys to the reader the notion of an open treeless plain, something akin to a prairie, it certainly has misled him. No such thing as a treeless acre of land exists in Malaya. The country is naturally and permanently covered with a heavy jungle; only where this is felled, burned off, and cleared of all weeds every three weeks or less, does open land exist.

| 8.1.1 |

The Coastal Plain |

The land to which I allude is the alluvial land between high-tide level and the nearest lower or Coastal Hills. In the course of our inquiry, it will be found convenient to consider malaria as it is found in the different zones of land existing in the Peninsula. The zone nearest the sea I propose to call the Mangrove Zone. Next will come the Coastal Plains; then the Coastal Hills. Still farther inland we come to areas of flat or relatively flat land which may be conveniently called the Inland Plains. Finally we come to the main range of hills forming the backbone of the Peninsula which I propose to call the Inland Hills. When opened up and inhabited, each of these areas presents special problems. It must not, however, be forgotten that in nature all are clothed in primeval forest; and that when inhabited they are in an unnatural, indeed a highly artificial, state. The Coastal Plain, in nature, is an alluvial flat composed of a heavy clay covered by dense, almost impenetrable, jungle. The ground water is almost permanently above the surface level; during the wetter months it may be waist deep. In some places the clay is covered with a coarse peat, formed from slowly decaying vegetable matter. Its depth varies from a few inches to many feet.

| 8.1.2 |

The mosquito of the virgin jungle |

Many mosquitoes have their home in this jungle; but practically the only anopheline is Anopheles umbrosus, which I found to be an efficient natural carrier of malaria. I use the word practically, for only on one occasion have I found another Anopheles in this virgin jungle. It was A. aurirostris. There may, of course, be others yet to be discovered.

A. umbrosus, as we saw (Chapter 2), may be present in enormous numbers. Generally speaking, it is so abundant in houses situated near to this jungle, that it may be obtained without difficulty; for, being a large black mosquito, it is easily seen. Sometimes, however, it disappears temporarily even from places where it is the rule to find it in abundance.

| 8.1.3 |

The relationship of Anopheles umbrosus to jungle: a working rule |

As we pass away from the jungle, the number of the mosquitoes decreases, and at half a mile (or 40 chains) the number has so decreased that malaria, as indicated by the spleen rate, has disappeared, although occasionally cases of malaria do occur. For many years this mosquito has been under observation, and its association with malaria studied. The sum of these observations is that malaria, in certain portions of the district, namely the flat land, is exclusively carried by A. umbrosus, which breeds in pools in undrained jungle; and when the jungle is felled and the pools drained, this mosquito is exterminated completely; and with its extermination malaria disappears. It has been found, too, that the spleen rate in the children decreases with the distance they live from the breeding places of the mosquito; and that the death rate of an estate varies as the spleen rate. Finally these facts have enabled me to forecast with considerable accuracy the probable health or unhealthiness of a proposed site for coolie lines, and to give advice which has borne fruit. A theory which will provide a sound working rule is one of considerable value.

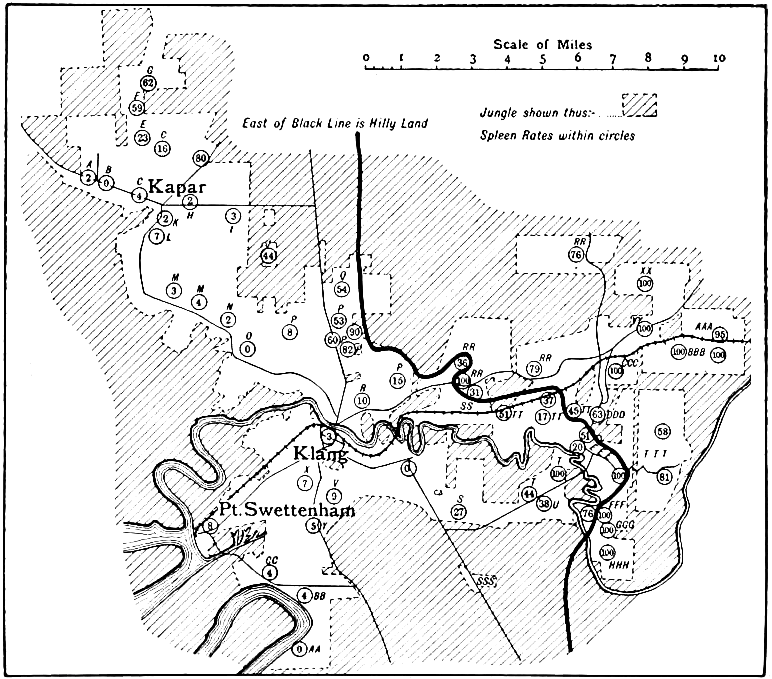

In order to make good these statements, I must now refer to the individual estates, the positions of which will be seen from the maps. In these are seen the parts under cultivation and the parts still (1909) undrained jungle. Coolie lines or houses are shown by the number, which is the spleen rate for the lines or group of lines at that part of the estate.

| 8.2 |

Details of estates |

| 8.2.1 |

Estate “A” |

This was opened in 1906, and the coolies were housed within 100 yards of the jungle (see Figure 8.1). In 1907 malaria was very prevalent among them, and it became necessary to administer quinine daily. Rapid progress, however, was made in opening up the land; and within a year there was an extraordinary improvement in the health of the estate. The most striking evidence is to be found in the reports of the Indian Immigration Department, from which the figures in Table 8.1 are taken.

| Year | 1907 | 1908 |

| No. on January 1st | 132 | 60 |

| Additions to labour | 261 | 173 |

| Died | 12 | 2 |

| Deserted | 34 | 7 |

| Discharged | 125 | 19 |

| Sent to India | 12 | – |

| Total deductions | 183 | 28 |

| No. on December 31st | 78 | 100 |

| Average population | 120 | 101 |

| Deaths (‰) | 100 | 20 |

These figures demonstrate the economic importance of malaria. The whole success and, in fact, the very existence of tropical agriculture depends on a healthy and contented labour force. The severe prevalence of malaria in 1907 led not only to a high death rate, but to the unnecessary loss, in other ways, of about 150 coolies. Coolies will not remain on an unhealthy estate; therefore, 34 deserted, 125 gave the legal month’s notice and left. Instead of having a fine labour force of close on 300 coolies, the estate had to begin the year with considerably fewer than it had the previous year.

In 1907 the manager, and a friend who had lived with him for some time, both suffered severely from malaria. On 23rd July 1907, only 167 out of 245 coolies were working, and of those not at work 10 had high temperatures. Three months later, after much loss of labour, I found on one occasion 8% of the labour force with fever, with oedematous feet, and the other sequelae of malaria.

The present manager has been on the estate for nearly two years. He has been off work for one day only and that not as a result of malaria, a disease from which he has not suffered. On 10th January 1910 I examined all the children on the estate,9 and out of the fifty-one examined, I found one with enlarged spleen, who, inquiry elicited, had come from an estate in another district, the death rate of which in 1908 was 108‰, and which I knew suffered severely from malaria. The child had malaria when it came to estate “A.”

I regret I have no figure referring to the children in 1907, but I consider the figures I have given demonstrate in the most striking way how malaria has disappeared with the draining and opening up of the land. Undrained jungle is now about half a mile distant from the lines. For its subsequent history see Chapter 21.

| 8.2.2 |

Estate “B” |

I first examined this estate in 1904, when all the nine children were found free from parasites. There was only a small labour force, about sixty in all, and only occasionally was there a case of fever. The jungle was comparatively near; but the land immediately behind the coolie lines was drained. I find, however, that a small labour force often escapes when a larger one is seriously affected. This estate has continued to enjoy good health throughout, and on 10th January 1910 none of the thirty children on the estate had enlarged spleen, and the conductor, who had been there for one and a half years, told me he had not had fever.

The death rates during 1906, 1907, and 1908 have been 22, 28, and 9‰, respectively. Since I came to know it, this estate has shown continued good health, although in 1907 its neighbour, only half a mile away, had suffered severely from malaria.

| Year | No. of children | Spleen rates (%) |

| 1912 | 30 | 6.6 |

| 1915 | 64 | 7.5 |

| 1916 | 70 | 8.5 |

The history of this estate during the subsequent ten years has been uneventful, except for an outbreak of cholera in 1911. Table 8.2 shows the spleen rates among children living on the estate. In 1912 two children had come from India two months before; both looked healthy and had not been ill. The death rates since 1909 are shown in Table 8.3.

| Year | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1916 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 |

| Deaths (‰) | 14 | 17 | 65 | 25 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 52 |

| 8.2.3 |

Estates “C,” “E,” “ F,” and “G” |

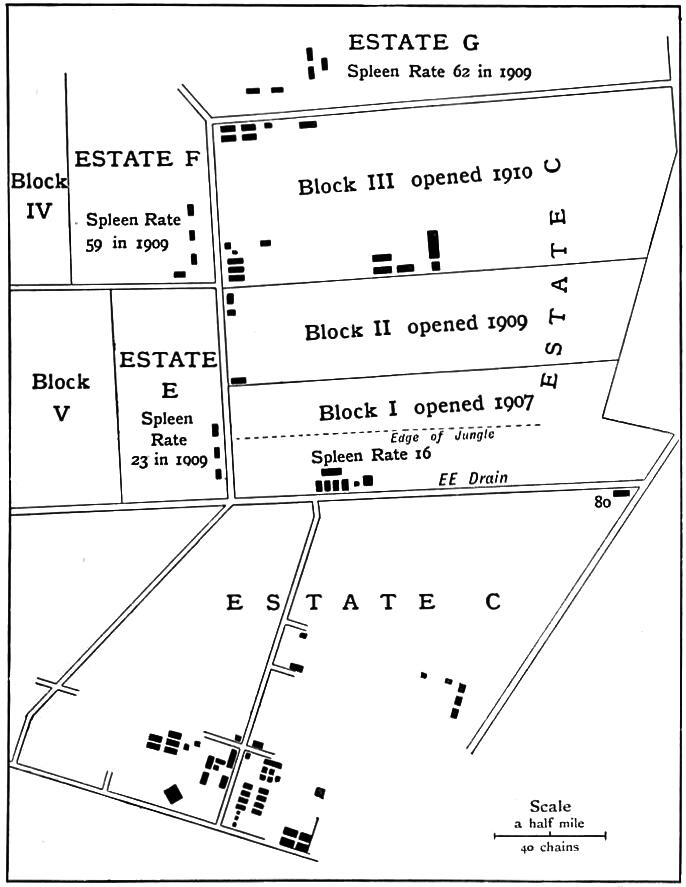

These estates illustrate clearly the association of malaria with undrained jungle. In 1909 they were being developed from virgin jungle, of which, of course, only a portion could be opened each year. During this period of development the labour forces were necessarily housed in varying proximity to the jungle; and all four suffered from malaria. It will be noted that at any time the incidence of malaria was greater the nearer a labour force was to the jungle; and that as the years passed it decreased pari passu with the disappearance of the jungle. The years in which the various blocks of land were cleared are marked on the plan (Figure 8.2).

Only part of the story could be told when the first edition of this book was written in 1909. Malaria had not yet disappeared from the upper division of estate “C;” estate “E” was only half-way out of the wood; the labour forces of estates “F” and “G” were still living close to jungle, and still suffering from intense malaria. But development was proceeding rapidly. It was a period of transition, which can best be recalled by reprinting what was written in 1909. Afterwards I will bring the story up to date.

| 8.2.4 |

Estate “C” |

This estate began operations in 1904, when its labour force was placed on land already opened a year or two before by Malays. They were thus placed on drained land from the beginning, and accordingly were healthy. Its death rate shows this, and was as listed in Table 8.4.

| Year | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 |

| Death ratea | 25 | – | 34 | 37 | 13 |

- a

- Presumably in ‰, but the original does not explicitly state this (M.P.)

An experiment was carried out on this estate in 1906 and 1907, which bore out the extraordinary limitation of the flight of the mosquito, the relation of malaria to undrained jungle, the importance of selecting the best site for the housing of a labour force, and the certainty with which one could predict the health or otherwise of a site on the flat land.

It is an estate of about 3000 acres, and, with the healthy labour force it possessed, such rapid progress was made that within three years of starting 1000 acres were already opened; and it was proposed to open still more. In 1906 much of the work of the coolies was one to two miles distant from their lines, and it was obviously an economy, both to the estate and the coolie, to house him nearer to his work.

I was informed in 1906 that it was proposed to remove most of the force to what would ultimately be the centre of the estate, which at that time was still on the edge of undrained jungle. Knowing from experience that the site would probably be very unhealthy, I strongly advised that only a few coolies should be removed until the land had been further opened up. However, four sets of lines were built, three about 25 chains, i.e., quarter of a mile from jungle; and the other about 100 yards. The removal took place in October 1906, and on 22nd November there were 120 coolies in the lines marked “Spleen Rate 16,” and 80 in a set of lines near to the jungle at quarter of a mile from the place marked “80” in Figures 8.1 and 8.2.10

The result was disastrous. The coolies were overwhelmed with malaria, and soon had to be removed. I am indebted to the manager, E. H. King-Harman, for the following explanation:

Re abandoning lines: You ask me my reason for abandoning four sets of coolie lines in March 1907. They are as follows: I found that amongst the coolies living near EE drain (place marked “16,” about twenty-five chains from the jungle) I had 28% down ill with fever every day, and amongst those living near to my bungalow, marked “80” about ten chains from jungle, the rate was 33% daily.

On that account I removed that portion of my labour force to the south-western end of the estate, which had previously been healthy, and I abandoned the top lines altogether; but about the beginning of 1909 I put a portion of my labour force back again near EE drain, the jungle being then forty chains away; and I am glad to say the fever rate has been very small, and of very little consequence.

On 22nd November 1906, there were fifteen children in the lines marked “16,” of whom only one had enlargement of the spleen. On 17th February 1907, there were twelve children, of whom seven, or 58%, had enlarged spleens. As these were the same children, it shows how malarious the place had become. On 4th January 1909, there were fifteen children living in the same place, of whom three had enlargement (very small in the case of two), equal to 20%. A portion of the force had only recently been removed to the edge of the drained jungle on block II, so that the figures for the whole division were thirty children, of which five, or 16% had enlarged spleens.

Now on the south-western portion of the estate, that is, the portion of the estate first occupied in 1904, I examined, on 5th January 1910, the children—in all 109. Of these, four had enlarged spleen, giving a spleen rate of 3.6%. They were recent arrivals. I recognised two sisters as being the only two children who had been found with enlargement on an estate in the neighbourhood; one other had come two months previously from an estate in another district; and one had come from an estate where the spleen rate was 100%. The corrected spleen rate should therefore be nil.

The bungalow to which the manager refers is still in occupation, and malaria is far from unknown to its occupants; while the bungalow on the south-western division has never been infected with malaria.

The medical history of this estate has been practically that of a series of experiments of the most convincing character. If any doubt remained, a glance at the map showing the condition of the estates marked “E,” “F,” and “G,” the coolie lines of which at the present moment vary in distance from jungle which has been drained for about one year only. The lines marked “23” had undrained jungle to within 200 yards about a year ago. Jungle is now about 500 yards distant, and it has been drained for about four months. The lines marked “59” on estate “F” are opposite and within fifty yards of jungle, which, however, has been drained for some months. The percentage of children with abnormal spleens was 59, based on the examination of thirty-two children. Of the thirteen with no enlargement, one has been one and a half years on the estate, three had been only fourteen days, while the others had been less than six months. It is interesting to note that the jungle opposite had been drained for about the same period, and this probably accounted for these children having escaped. Dr. T. S. Macaulay kindly examined the blood of twenty children on this estate, and found parasites in seven, or 31.9%. These children got about 5 grains of quinine daily.

On 6th December 1906, I examined three children on this estate, and of these two had considerable enlargement of the spleen. The death rate of the estate in 1908 was 41‰.

| 8.2.5 |

Estate “G” |

This estate has been unhealthy since it was opened, as undrained jungle has always been within less than 100 yards of all the coolie lines. On 5th January 1910, I examined twenty-four children on this estate, and of these fifteen had enlarged spleen, equal to 62%. Of the nine with no enlargement, two had been only fourteen days on it; and one had a high temperature at the time of my examination. Dr. Macaulay examined the blood of eleven of the children on this estate, but did not find parasites. All were on quinine, about 5 grains daily.

On 6th December 1906, I examined eight children on this estate and found three, or 37%, with enlarged spleen. The death rate given in the Indian Immigration Return is 69, but this does not represent the exact death rate, since estate “M,” which belongs to the same company, had an estate hospital, to which the sick from this estate were sent. Those who died there were not accredited to “G,” but swelled the death rate of estate “M,” to an unnatural degree. I will draw attention to this later.

From these figures it is evident that the opening up of the estates “F” and “G” did not lead to any improvement in their health; and the reason was obviously that the lines were still as near to the jungle as when the estates were first opened. This is in marked contrast to the improvement to be seen where the opening of the estates pushes the jungle away from the lines.

Such were the conclusions reached in 1909. If they were correct, and if jungle swamp was the cause of the malaria, then the health of estates “F” and “G” could not be expected to improve until they moved their labour forces away from the block of jungle marked III or until the jungle was opened up. Time proved the conclusions to be correct. In due course the jungle was opened; so too were the blocks marked I, II, IV, and V. Then, and not till then, the high spleen rates fell, as the records in Table 8.5 show. Jungle Block I was opened in 1907, block II in 1909, and blocks III, IV, and V in 1910.

| Estate | Proximity to jungle | Year | No. of children | Spleen rates (%) |

| Ca | Lower division of estate; lines never near to jungle | 1910 | 108 | 3.6 |

| 1913 | 237 | 1.2 | ||

| 1915 | 223 | 1.7 | ||

| 1917 | 301 | 2.2 | ||

| Upper division; line 100 to 400 yards from jungle | 1909 | 30 | 16 | |

| 1913 | 109 | 2.7 | ||

| 1917 | 138 | 3.6 | ||

| E | Line 200 yards from jungle in 1908 | 1909 | 13 | 23 |

| 1911 | 18 | 11.1 | ||

| 1913 | 20 | 15 | ||

| 1915 | 31 | 10.7 | ||

| 1917 | 39 | 2.5 | ||

| F | Lines next to jungle drained in 1909 | 1906 | 3 | 66 |

| 1910 | 32 | 39 | ||

| 1912 | 32 | 24 | ||

| 1913 | 92 | 2.1 | ||

| 1915 | 76 | 14.4b | ||

| 1917 | 83 | 4.8 | ||

| G | Lines next to jungle drained in 1909, and planted in 1910 | 1906 | 8 | 37 |

| 1910 | 24 | 62 | ||

| 1911 | 62 | 6 | ||

| 1913 | 110 | 1.8 | ||

| 1915 | 76 | 11 | ||

| 1917 (Feb) | 118 | 2 | ||

| 1917 (Sep) | 111 | 10 |

- a

- The death rates of estate C from 1906 onwards have been as follows: 34, 37, 13, 3, 11, 13, 15, 7, 5, 8, 13, 23, 31, 12.

- b

- These figures included eight children from a malarious estate.

So we see how hundreds of healthy children now live on places which only a few years ago were most malarious. Further comment on the figures is superfluous, beyond a reminder that just as the labourer is free to leave a healthy estate when attracted by the higher wages of an unhealthy one, so he often returns when ill, and he and his sickly children raise the death rate and spleen rate of the healthy estate. For example, eight of the eleven children with enlarged spleen found on estate “F” in 1915 had recently come from an unhealthy estate. It is easy to ascertain a fact like that, and so the correction of spleen rates is easy. In the course of this book, many such instances occur. As it would merely burden the narrative unnecessarily to give details in every instance, it will be done only in some.

| 8.2.6 |

Estate “H” |

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 25 | 13 | 27 | 26 | ||

| Infected (%) | 28 | 48 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 27 | 58 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 0 | 1.6 | |||||

| Death rate | 30 | 30 | 22 |

The medical history of this estate can be found from Table 8.6. Now from these figures it is obvious that a marked improvement occurred in the health of this estate in 1906. I give in the manager’s own words the explanation:

In answer to your inquiry with regard to the health of this estate: In 1904 only 160 acres were opened and jungle came comparatively close to the lines. There was so much fever that coolies had to be dosed with quinine daily at muster. Little opening was done during 1905, and the state of health among coolies remained much the same. In 1906 jungle was carried back by opening to a distance of one and a quarter miles on one side and about half a mile on the other, and from that date there has been practically no fever on the estate and the out-turn of coolies daily has improved to a marked extent.

Dated 5/1/10. N. C. S. Bosanquet.

Comment on this is hardly necessary, but I might mention that the lines were distant from the jungle in 1904 about a quarter of a mile. The extra quarter of a mile made all the difference. Being a quarter of a mile away to begin with the estate was not suffering so severely from malaria as would have been the case had the lines been closer, but I think the lesson can hardly be missed.

The health on this estate has continued good (see Table 8.7). Malaria has never returned. The death rates have been equally satisfactory; from 1906 inclusive they have been: 30, 30, 22, 5, 13, 24, 14, 10, 2, 8, 23, 20, and 15‰.

| Year | No. examined | Spleen enlarged | Spleen rates |

| 1911 | 73 | 3 | 3.7 |

| 1912 | 83 | 2 | 2.4 |

| 1914 | 66 | 2 | 2.7 |

| 8.2.7 |

Estates “I” and “J” |

Opened in 1904, this estate suffered very severely from malaria, more so than the percentage of children infected in 1905 would lead one to suppose. It was so severe that not a child below the age of one year was to be found on the estate; although the adult labour force was then about 250. The manager suffered so severely from the disease that he had to be sent on three months’ leave of absence. In December 1905, I saw no fewer than seventeen coolies, or 6-8% of the whole labour force ill with malaria fever, while diarrhoea and dysentery, the common terminal sequelae of malaria, were far from uncommon. Then, in 1906, opening up having been continued, improvement took place (see Table 8.8). The present manager had been on the estate for over three years and had not had malaria. The jungle is now (1909) rather less than half a mile from the lines.

| 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 15 | 16 | 59 | ||

| Infected (%) | 26 | 0 | 1.6 | |||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 58 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 1.4 | |||||

| Death rate | 68 | 54 |

In subsequent years the jungle was pushed back still farther, and the good health was maintained. In 1913 there were eight children with enlarged spleen out of 129 (6.2%); in 1915, two children out of 177 (1.1%). Further comment is superfluous.

We have thus seen that, on the same road on two different estates, the lines, which were near to the undrained jungle, were unhealthy; and that when the jungle was pushed back, the lines became healthy. Yet there has been no general change in the country; for we find that, at the present date (1909), we have only to go to the lines still on the jungle edge to find malaria. Immediately inland from estate “I”, we come to estate “J”; and here of the nine children, four, or 44% have enlarged spleens. Quinine was given systematically on the estate, and doubtless this kept the death rate comparatively low. It was 34‰ in 1908, and 120 in 1907.

The jungle next to the coolie lines on estate “J” is still there. It is now reduced to a strip 80 chains wide; on both sides and at the ends, the land has been opened, drained, and cultivated for long distances. The jungle grows on a clay, covered by a deep layer of peat; in very wet weather, water stands on the surface, so only during a short period of the year is it a breeding place for Anopheles. The result is that the health of estate “J” has materially improved; sometimes, in the wet months of the year, a few malaria cases appear; but the low spleen rates show how little there is (see Table 8.9). A similar condition of health exists on another estate close to estate “J” and similarly close to jungle. Out of twenty children examined not one had an enlarged spleen; but malaria does occur at times in the wet months.

| Year | No. of children examined | Spleen rates |

| 1909 | 9 | 44 |

| 1913 | 41 | 0 |

| 1915 | 34 | 0 |

| 1917 | 41 | 4.8 |

| 1919 | 61 | 0 |

The story of how malaria has disappeared from estates on flat land, as the jungle has been pushed back to about half a mile, little short of miraculous as it is, becomes monotonous as we trace it north up to Kuala Selangor, and down south through Klang to Kuala Langat, over a distance of some fifty miles. The maps, indeed, tell the tale. I would gladly leave it at that, but the subject is of such economic importance that I must make the proof of the improvement as full as possible. For, marvellous as the disappearance of malaria has been with the opening up of the flat land, just as striking has been the total failures of similar opening to affect malaria on the hilly land. The explanation of the difference is to be found in the mosquito theorem; that alone can explain it. On the flat land the carrier of malaria is the mosquito, A. umbrosus, which, breeding in pools in the jungle, is exterminated when these pools are drained even by open drains; while on the hill land, the chief carrier is A. maculatus, a mosquito which cannot be exterminated in the ravines by open drainage, however quick the current, since its proper breeding place is the running water of springs and hill streams.

My object, therefore, even at the risk of being tedious, is to show that on flat land the manager of an estate can put his coolie lines, in almost every instance, beyond the reach of the malaria carrier, and so save his labour from malaria; and I maintain that, since over thousands of acres of flat land malaria has been abolished by extermination of the mosquito which carries the disease, so the manager of the hill estate can also abolish the disease if he abolishes the breeding places of the hill-carrier by putting the water of the ravines underground.

Estate “K” is small, and I have few figures referring to it. Its coolie lines have always been at a distance from jungle, and have always been healthy. I am indebted to Dr. Macaulay for examining the fourteen children on this estate. Of the fourteen he found one with an enlarged spleen, equal to 7%. This child, however, came from an estate on which the spleen rate is 23, and had suffered from fever before coming to estate “K”. The death rate of this estate was 18‰ in 1908.

In 1912 and 1916 the number of children examined was 30 and 129 respectively. No enlarged spleen was found on either occasion. The health of the estate has remained uniformly good.

| 8.2.8 |

Estates “L” to “Q” |

Their spleen rates, as given on the map (Figure 8.1), show that those away from the jungle are healthy, while those close to it are more unhealthy; and that, even on the same estate, there are marked differences of health depending also on the proximity or otherwise of the lines from the jungle. Estates “L,” “M,” “N,” “O,” are all at some distance from the jungle, and all are healthy. Estate “P” has some lines near to the jungle, and these are very unhealthy; while others away from it are healthy. Estate “Q,” on the other hand, had all its lines close to jungle until recently, and some remain so; and its spleen rate is high.

Dealing with these estates in detail, we find that during the course of the past few years some of those, which are now healthy, were unhealthy when the lines were closer to jungle.

| 8.2.9 |

Estate “L” |

This estate, begun in 1902, had already a considerable area opened and drained by November 1904, when I first made an examination of the children. Table 8.10 shows the result of blood and spleen examination of children, and the death rate of Estate “L.” Dr. Macaulay, to whom I am indebted for the examinations in 1909, says that of the thirty-nine children, the only one with enlargement of the spleen was a child eight months old, born on the estate. The enlargement was so slight that he could hardly call it pathological. Here again we see the improvement which has followed the abolition of the malaria carrier, for A. umbrosus can no longer be found on this estate.

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 10 | 16 | 18 | |||

| Infected (%) | 33 | 6 | 0 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 18 | 39 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 0 | 2.5 | |||||

| Death rate | 20 | 21 | |||||

In 1912 there were ninety-five children on the estate, none of whom had enlarged spleens.

| 8.2.10 |

Estate “M” |

This estate was first opened in 1898, and I cannot recall the time, since I came to the district in 1901, when it was unhealthy. Such figures as I have show this (Table 8.11).

| 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 26 | 25 | |||

| Infected (%) | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 25 | 202 | |||

| Enlarged (%) | 4 | 3.4 | ||||

| Death rate | 15 | 26 | 35 | |||

That the estate is free from malaria is shown by the fact that no European has contracted malaria on it since I came to the district; and there is now, and has been for several years, a European staff of six.

Table 8.12 shows the spleen rates in recent years. The Europeans have continued to be free from malaria.

| Year | No. examined | No. enlarged | Spleen rates |

| 1912 | 57 | 1 | 1.7 |

| 1914 | 138 | 6 | 4.3 |

| 1916 | 128 | 3 | 2.3 |

| 8.2.11 |

Estates “N” and “O” |

The lines of both the estates are now a considerable distance from the jungle, the nearest being the mangrove, which is 600 to 1000 yards off.

I have few figures concerning these estates. I remember on one occasion in 1905 visiting a set of lines on “N” and found many cases of fever. It was then within 100 yards of the jungle. Unfortunately, I cannot find my notes of this. The figures in Table 8.13 show that the estates are not by any means unhealthy. The labour force is small on each, being only 280 on “N” and 120 on “O”.

| Death rates | Spleen rates (1909) | ||||

| Estate | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | No. examined | Enlarged (%) |

| “N” | 8 | 20 | 43 | 29 | 0 |

| “O” | 44 | 18 | 34 | 45 | 2.2 |

| 8.2.12 |

Estate “P |

This is one of the largest estates in the country, and stretches over several square miles. Within its boundaries are to be found lines at varying distances from undrained jungle. These show in the most distinct manner what has been evident on all the other estates to which I have previously referred.

It will be seen from a reference to the map, that the lines 82 are close to the jungle. They contained seventeen children, of whom fourteen had enlarged spleens. Farther along, on the edge of the same jungle, are lines containing eleven children, of whom ten have spleens abnormal in size, giving a rate of 90.9%. Two hundred yards from these the lines containing fifteen children showed a spleen rate of 53.3%, while at a distance of 300 yards from the lines marked 82 the spleen rate of twenty-two children was 59.9%.

In marked contrast to these are the 109 children who live at a greater distance from the jungle and whose spleen rate is 8.2. That it should be so high as this is due to some of the lines being near to a small belt of jungle once drained, but whose drains are not upkept. When the lines were put there in 1906 I have notes showing that there were considerable numbers of cases of malaria on the estate, and I recollect that these were unhealthy; but, unfortunately, I have not recorded the exact number of cases found in each of the different sets of lines. There is no doubt, however, that these lines next to the belt of jungle have improved in health to a very considerable extent. In tabular form these facts become more evident (see Table 8.14).

| Distance from undrained jungle | |||

| <100 yards | 200-300 yards | >600 yards | |

| No. of children examined | 28 | 37 | 109 |

| No. with enlarged spleen | 24 | 17 | 9 |

| % with enlarged spleen | 85.7 | 45.9 | 8.9 |

For the subsequent history of estate “P,” see Chapter 16.

| 8.2.13 |

Estate “Q” |

The lines on this estate also vary in distance from one hundred yards to a quarter of a mile from the jungle. I found, however, that the coolies had been moving from the lines nearest to the jungle to others farther away. I therefore cannot determine with accuracy the spleen rate of the different lines. The lines a quarter of a mile from jungle have a spleen rate of 28, while that of those within 100 yards is 59.3. The other rates are 55.5, 42.9 and 60, and that for the whole estate is 53.6.

The death rate was 60 per 1000 in 1908. For the later history see Chapter 16.

| 8.2.14 |

Estate “R” |

Within 150 yards of the lines on this estate is a small swamp about half an acre in extent. There is no other swamp within half a mile.

Of nineteen children examined in 1910, 10.5% had enlarged spleen. The death rate of the estate has been 40, 56, and 45 in the years 1906, 1907, and 1908 respectively.

There are other two records of the spleen rate of this estate. In 1915 and 1916 there were 32 children; on each occasion one child had enlarged spleen, giving a rate of 3.2. The child had returned to estate “R” after having bolted to an unhealthy estate.

| 8.2.15 |

Estate “S” |

Passing south across the Klang River we come to estate “S” which has been opened for some years. Although extensive in area, the opening has not been such as to decrease the distance of the lines from the nearest jungle. Table 8.15 gives the facts.

| Distance of various lines from jungle | |||||

| 200 yards | 300 yards | 350 yards | 300 yards | 200 yards | |

| No. examined | 4 | 7 | 13 | 8 | 20 |

| Spleen rates | 50 | 28.5 | 23.0 | 37.5 | 20 |

There has been a great improvement in the health of this estate during 1909 due to the extensive use of quinine. It is an example of how quinine may appear of greater value in a place where malaria is not very severe than where the disease is intense.

The estate has always been unhealthy, but not intensely malarious, the spleen rate of the whole estate being only 23; still the disease has caused considerable trouble. There are no official figures for 1907, but in that year the manager was invalided to Europe on account of malaria. In the same year a large gang of coolies also left on account of the disease. In 1908 there was great sickness; and I saw many cases of chronic and acute malaria on the estate. In the months of November and December, no fewer than sixteen coolies died from malaria and its complications. The whole labour force was then put on to quinine—ten grains daily, and the death rate at once came down. Of the six deaths in 1909, none was due to malaria either directly or indirectly. The figures are interesting (Table 8.16).

| Year | Average population | Deaths | Desertions | Discharges | Total loss |

| 1908 | 362 | 42 | 137 | 230 | 409 |

| 1909 | 373 | 6 | 46 | 172 | 224 |

This is the only estate on which quinine is given systematically, the spleen rate of which is below 40. I refer to the subject of the dose of quinine in relation to the intensity of the disease in Section 12.6.

The subsequent history of this estate is of great interest, as is that of another estate subsequently opened beside it. It will be found in Chapter 22 on the Reappearance of Malaria.

| 8.2.16 |

Estates “T” and “U” |

The next two estates I deal with together, as they form practically one clearing in the middle of jungle.

On Estate “T” one set of lines is close to jungle, about 50 feet from it, and of three children all have enlarged spleens; while, in the set of lines 100 yards from jungle, nine out of ten have enlargement. The spleen rate of these two sets of lines is therefore 92.3%.

The other lines on the two estates are close to each other, and about one-third of a mile from jungle Of the fifty-four children twenty-one suffer from enlargement, giving a spleen rate of 38.8%.

The rate of the whole sixty-seven children on the two estates in 1909 is thus 49.2%. On the 16th January 1907, I examined forty-four children on these same estates and found twenty-six with enlarged spleens, giving a rate of 59%. It will thus be seen that here again the lines near to the jungle are the more unhealthy, and that during the last three years, because the nearest jungle is still at the same distance from the lines, there has practically been no improvement in the health. The death rates bear this out (Table 8.17).

| 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | |

| Estate “T” | 72 | 33 | 107 |

| Estate “U” | 37 | 64 | 75 |

Development has proceeded rapidly since that was written in 1909. Except for a small area of perhaps 5 or 6 acres, no jungle exists within three-quarters of a mile of the lines; in many directions, it is over a mile away. The health has improved according to rule. In 1919 the spleen rate of 177 children on estate “T” was 16%.

| 8.2.17 |

Estate SSS |

Estate “SSS”, a small clearing in the jungle, follows the usual rule. No coolies can be kept on it, as it is so unhealthy.

| 8.2.18 |

Estates “V”, “X”, “Y”, “AA”, “BB”, “CC” |

Turning back towards the coast, we come to these estates, which are among the oldest in the district, and have large areas opened up. On all, with one exception, the lines are at a distance from jungle, and the health of all is good. It was not, however, always so. I remember, when District Surgeon, that cases of malaria were not infrequently admitted from estate “V”; while in the first half of 1906 I find from my notes that malaria was constantly seen in the lines of estate “X”, which are marked 7, and which were then on the edge of the jungle. I have, however, no figures referring to the children. Table 8.18 shows their present condition.

| “V” | “X” | “Y” | “AA” | “BB” | “CC” | ||

| Number examined | 32 | 85 | 145 | 26 | 25 | 82 | |

| Spleen rate (%) | 9.6 | 7.0 | 4.8 | 0 | 4 | 3.6 | |

| Death rate | 1908 | 11 | 30 | 29 | 22 | 22 | 9 |

| 1907 | 6 | 25 | 35 | 20 | 30 | ||

| 1906 | 0 | 67 | 23 | 38 | 20 | 30 | |

It is hardly necessary to comment on these figures. But on estate “V”, of the three coolies with enlarged spleens, one came from a set of lines on another estate the spleen rate of which is over 50. In April 1909, Dr. Stanton, of the Institute for Medical Research, examined 160 unselected coolies on this estate, and found only two, or 13%, with malaria parasites in the blood.

Although the estate is classed among those of the flat land, it is not entirely flat. Part of it is hilly. The absence of malaria is due to the valleys between the hills being of such a formation that no proper hill streams are found, and A. maculatus cannot be found either in the drains or in the lines of the estate. Klang Town is also hilly, but here again there are no hill streams in which A. maculatus breeds.11 Hence open drains sufficed to eradicate malaria. An idea was prevalent among medical men at one time that malaria was due to a disturbance of hill soil, the exposure and excavation of red earth, and the quarrying of laterite.

The absence of malaria from estate “V”, where red earth and laterite are abundant, from the town of Klang where the constant quarrying of laterite and the excavation of red earth have gone on for years, from the midst of the town and at the hospital, shows that malaria is not due to the presence or disturbance of these soils. The one constant condition which I have found associated with malaria is the presence of certain species of Anopheles. It is true that, in some of the most malarious places, it is said by the layman that there are no mosquitoes. On one such place, an estate where the spleen rate is 100% and the death rate in 1908 was 30%, the manager, a man of more than ordinary intelligence, assured me that mosquitoes were never seen except on a wet night, and then only in small numbers. My experience was that, whereas the man who helps me to catch mosquitoes usually earns 20 or 30 cents in a couple of hours, being paid at the rate of 3 cents for each anopheline, on this estate he earned 3 dollars and 12 cents in the same time, and at the same rate; having thus caught 104 anophelines. When I went to the lines I found the mosquitoes, mostly A. maculatus, in great abundance. A. maculatus is a small mosquito; it makes little noise and causes little, if any, pain when it bites. This is different from A. umbrosus, which gives a painful bite something like a sharp hot needle.

The town of Klang and estates “V” and “X” remained free from A. maculatus until 1913. Fortunately for estate “V” they came mainly to a small ravine more than half a mile from the coolie lines of the estate; unfortunately for estate “X” they were within 100 yards of its lines, in which they produced a serious outbreak of malaria. (See Chapter 22) Estate “V” continues to be healthy as the spleen rate shows (Table 8.19).

| Estate | Year | No. examined | No. enlargeda | Spleen rates (%) |

| FF | 1909 | 13 | 3 | 23 |

| 1915 | 56 | 18 | 32 | |

| 1917 | 99 | 5 | 5 | |

| GG | 1914 (May) | 32 | 4 | 12.5 |

| 1914 (Dec.) | 113 | 3 | 2.6 | |

| 1917 | 138 | 0 | 0 | |

| HH | 1909 | 46 | 25 | 54.3 |

| 1915 | 200 | 6 | 3.0 | |

| 1917 | 257 | 9 | 3.3 | |

| JJ | 1917 (Jan.) | 112 | 1 | 0.8 |

| 1917 (Oct.) | 165 | 2 | 1.2 | |

| KK | 1914 | 135 | 1 | 0.7 |

| 1917 (Jan.) | 135 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 1917 (Oct.) | 155 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| LL | 1914 | 209 | 3 | 1.4 |

| 1917 (Jan.) | 226 | 2 | 0.8 | |

| 1917 (Oct.) | 246 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| MM | 1915 | 121 | 3 | 2.4 |

| 1917 | 131 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| NN | 1909 | 35 | 4 | 11.4 |

| 1917 (Jan.) | 238 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| 1917 (Dec.) | 190 | 2 | 1.0 | |

| OO | 1915 | 177 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 1917 | 130 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| PP | 1915 | 41 | 3 | 7.3 |

| 1917 | 63 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| TT | 1915 | 80 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 1917 | 126 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| V | 1915 | 73 | 5 | 6.8 |

| 1918 | 79 | 2 | 2.5 |

- a

- Some figures in this column were missing from the tables in the original text; they were back-calculated from the other two columns (M.P.)

Of the six children on estate “X” with enlarged spleen, three had been on the estate only fourteen days, having come from India. The presumption is that these children had malaria before their arrival on the estate. The high death rate of this estate in 1908 was due to the return to the estate of a gang of coolies, eighty in number, who had gone to an estate whose spleen rate is 100%. They suffered so severely from malaria there that they returned at the end of six weeks. The manager of estate “X” was afraid these coolies might infect the others, but this did not occur since there was no anopheline to act as carriers.

On Estate “Y” seven of the lines were close to jungle, which, although drained on the two sides which are close to the lines, could not be called properly drained. Three years ago, however, I was unable to find anophelines in it on one single occasion. Of the ninety children in these lines 5.2% had enlarged spleen, while in another set of lines close to drained jungle twenty-two children showed a spleen rate of 8.3%. The spleen rate of the remaining thirty-three children who were housed about half a mile from the jungle was nil.

This is the only estate which even appears to be an exception to the rule that lines within 200 yards of the jungle should have a spleen rate of about 50%, but the presence of a large 15-foot drain along one side of the jungle and a 6-foot drain along the other side, as well as the fact that the jungle here is peaty, probably explains the freedom from sickness.

At times large numbers of A. umbrosus temporarily appear in the lines and bungalows of this estate.

The health of Estate “BB” has continued to be excellent; the spleen rate in 1915 was 1.36 (−2.8%). The death rates from 1907 to 1918 inclusive have been 20 to 23, 19, 21, 25, 7, 8,0, 3, 16, 8, and 19.

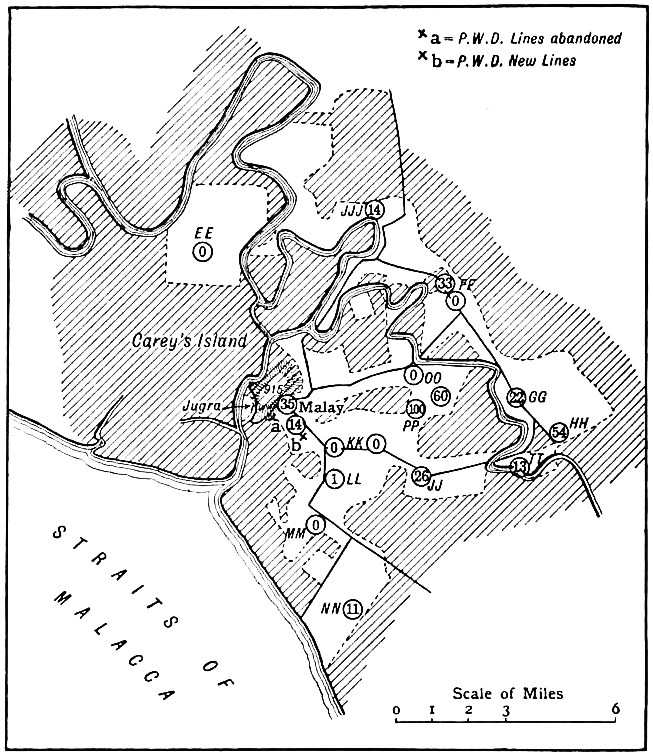

Passing on to the Langat District again, we come to a small estate, “JJJ”, the lines of which are a little over a quarter of a mile from jungle. The spleen rate of the twenty-one children is 14. The death rate in 1908 was 1.9%.

| 8.2.19 |

Estate “FF” |

The next estate is “FF”, and in the lines next to the jungle the rate is 33, while in the more distant lines it is nil. For the whole estate it is 23.7%, and the death rate for 1908 was 5.3%.

As years passed the estate grew in size; the labour force was housed in three different areas or divisions, the latest still farther from the jungle than the other two. I shall call them Divisions I., II., and III.

Division I. next to the jungle maintained its high spleen rate; and each wet season saw a number of malaria cases, with rarely a death; for more than ordinary care is taken with this labour force. The chief difficulties in making the estate healthy were a special jungle reserve for “Sakais”, one of the native races of the Peninsula; and the prohibitive prices the surrounding natives placed on patches of swampy kampongs.

In 1915, however, the kampongs were cleaned up and drained, and by 1917 the estate had reaped the benefit of these measures, as the figures in Table 8.19 show. These figures are for the whole estate. It is not necessary to go into details; they simply show that as long as the spleen rate of the estate was high, it resulted from the children living next to the jungle. Division III. was from the first free from the disease.

| 8.2.20 |

Estate GG |

Farther on, Estate “GG” has a spleen rate of 2.2% (fifty-nine examined), although the lines are a quarter of a mile from jungle and separated from it by a river. On this estate were eighteen children, of whom ten had enlarged spleen. These came from an estate whose rate is about fifty. By deducting these children the corrected rate of the estate would be 7.3%.12 The death rate of the estate in 1908 was 31. It has been healthy from the beginning as it began on open land.

Nothing much of note has to be recorded: the health has continued to be good. The spleen rates are given in Table 8.19. Of the four children found with enlarged spleen in 1914, three belonged to a family which had left the estate for a time to live at Jugra Hill, a very malarious place (see Section 16.6); there the father died of malaria; the widow and children then returned to the estate.

At the muster in 1917, I was interested to see three of the eighteen children, mentioned as having come from a malarious estate in 1909, now mothers with healthy babies in their arms.

| 8.2.21 |

Estate “HH” |

In marked contrast to this is the next Estate “HH” only half a mile farther on; where all the lines are within a hundred yards of jungle. Of forty-six children 54.3% had enlargement of the spleen, and in 1908 the death rate of the estate was correspondingly high, namely 6%.

In 1909 “HH” was an estate of only a few hundred acres; today there are over 4000 acres, except for a narrow strip of swampy jungle on the stiff clay soil of the river bank, jungle is everywhere distant from the lines. Five out of the nine children with enlarged spleen were among 42 on the division nearest the strip of jungle on the river bank. Table 8.19 shows the spleen rates observed on this estate.

| 8.2.22 |

Estate “TT” |

Estate “TT” has a spleen rate of only 13 in the fifteen children examined. The lines are about 200 yards from jungle, but are separated from it by a river. Its death rate in 1908 was 47.

The jungle on both sides of the river is now opened; in fact, a portion of the labour force now lives on the opposite bank. Table 8.19 shows the spleen rates for this estate in 1915 and 1917. Both children with enlarged spleen in 1917 were on the old division.

| 8.2.23 |

Estates “JJ”, “KK”, and “LL” |

These three estates again corroborate the evidence which we have been so steadily accumulating. Estate “JJ” has lines within a quarter of a mile of jungle and the spleen rate of fifty-three children is 26.3%. Its death rate was 39. The figures (Table 8.20) tell their own tale.

| Estate | Distance lines are from jungle | Spleen examination | Death rate 1908 | |

| No. examined | Enlarged (%) | |||

| “JJ” | 400 yards | 53 | 26.3 | 39 |

| “KK” | >1000 yards | 48 | 0.0 | 12 |

| “LL” | >1000 yards | 70 | 1.4 | 17 |

The only child found on estate “LL” with enlarged spleen had come from an estate whose spleen rate was between 30 and 40%.

All three are now free from malaria; no jungle is near to any of them. The spleen rates observed in recent years are listed in Table 8.19. The examinations in 1917 were by different European observers.

| 8.2.24 |

Estates “KK” and “PP” |

Adjoining estate “KK” are two estates illustrating the same rule. Estate “PP” is a small one, but the manager and his coolies suffer considerably from fever. The two children on it had both enlarged spleens. They all live within a hundred yards of jungle. In due course the jungle was opened up and health improved (see Table 8.19). The three children with enlarged spleen belonged to one family, which had arrived from India only 11/2 months previously.

| 8.2.25 |

Estate “OO” |

Estate “OO” has lines in two places. One set of lines is now half a mile from jungle, but until recently the jungle was only a quarter of a mile away. The other set of lines are, and have been, half a mile from jungle for about two years. The result is very striking; for, whereas in the lines which were until recently a quarter of a mile from jungle, 60% of the twenty-eight children examined suffered from splenic enlargement, of the seventeen in the other lines, the spleen rate was nil.

Here, too, with the development of the estate, the jungle was pushed farther from the lines and the health improved (Table 8.19). The only child with enlarged spleen in 1917 had come from Seremban (an unhealthy district) one month before. The death rates from 1907 to 1918 inclusive have been: 40, 40, 21, 29, 27, 15, 14, 13, 2, 7, 12, 17, the last being the year of the influenza pandemic.

| 8.2.26 |

Estates “MM” and “NN” |

Until recently the lines on Estate “NN” were one third of a mile from jungle. The spleen rate of the thirty-five children is 11.4%; while the lines of Estate “MM” are over 1000 yards from jungle and none of the twelve children have abnormality of the spleen.

The spleen rates for these estates have been as shown in Table 8.19. Estate “MM” has continued healthy. Estate “NN” is now one of the largest in the district; it is divided into two divisions a few miles apart. The girl with enlarged spleen in January 1917 had recently come from India. She had not suffered from fever on the estate, and had worked regularly without missing a day. At the November examination, her spleen could not be palpitated, nor was splenic dullness enlarged to percussion. Of the two with enlarged spleen in November, one was a returned bolter, the other had suffered from fever on the estate a month previously.

| 8.3 |

Disappearance of malaria from certain rural areas |

It is sometimes argued that malaria is never as severe on flat land as it is on hilly land. This is generally so, for the conditions from the first are different. On hill land, the coolies are housed on the side of a ravine so that water may be conveniently to hand. They are, therefore, placed as close as possible to the breeding places of the malaria carrier, that is on the most unhealthy spots on an estate, and there they remain. No further opening of the estate alters the distance they are from the breeding place.

In the case of flat land estates the conditions are entirely different. Before a Tamil coolie is brought to an estate, at least fifty acres are felled, drained, and burned by Javanese, people who are, as we shall see, generally immune to malaria. The Tamil on the flat, therefore, starts with the breeding place of the malaria carrier at a distance of some hundreds of yards, and every few months further openings put the breeding places farther off. He starts, therefore, under better conditions as a rule, and the conditions improve with every additional opening.

That there is no essential difference is seen if a non-immune population is placed on undrained flat land. The conditions are then the same as on hill land, and the results are the same. It is not often, of course, that we see a population under such circumstances; but it occurred at Port Swettenham in 1901, and there malaria was as severe as it ever was on any hill estate.

We have seen, too, that lines close to the jungle have 90 to 100% of the children suffering from enlarged spleen, and the occurrence of a case of blackwater fever in a European, who lived within 100 yards of the jungle on the flat land, supplies a further proof, if the history of Port Swettenham has failed to convince.

| 8.4 |

Summary of examination of children on flat land estates |

On the flat land estates altogether 2,295 children were examined in 1909. Tabulating the results, we find that the health of the lines bears a very definite relationship to their distance from the jungle (see Table 8.21).

| Distance from jungle (yards) | |||||

| <300 | 300-600 | 600-1000 | >1000 | Total | |

| No. examined | 325 | 396 | 532 | 1042 | 2295 |

| Spleen rates (%) | 47 | 21.9 | 11 | 2.6 | 14.6 |

It is clear from these figures that malaria can be avoided on the flat land by housing coolies about 1000 yards from the nearest undrained jungle, and that every yard the coolies are removed from jungle improves their health.

In a later table it will be seen that the death rate of estates in Malaya is largely due to malaria, and that were malaria abolished the death rate would be about 10‰ of the coolie population as at present constituted.

Over an area of the Selangor coast, some fifty miles long, I have traced how malaria, affecting a population of many thousands, has been driven back, year by year, as the land has been drained and opened by agricultural operations.

At the towns of Klang and Port Swettenham, deliberate attempts were made to deal with the disease; and they were successful in the highest degree.

But of infinitely more importance have been the results of the agricultural operations. Although malaria may affect a town, it is essentially a disease of the country. The capital of the peasant is his health, and if this be destroyed by malaria, poor, indeed, is he. The planters in Malaya have carried out—unconsciously, it is true—what really forms an extensive series of rural anti-malarial and anti-mosquito experiments. I have watched, over a number of years now, experiment after experiment, with control after control, which have proved that the pool-breeding anopheline, which carries malaria on the Coastal Plain of Malaya, can be exterminated by open drainage at a very low cost; and that with the extermination of the anopheline, malaria has disappeared. Anti-mosquito measures have, therefore, been proved on the coast of Malaya to be not only entirely suitable to rural districts, but have greatly improved the value of the land.