| 10 |

The Coastal Hills |

| 10.1 |

The persistence of malaria in certain rural areas (1920) |

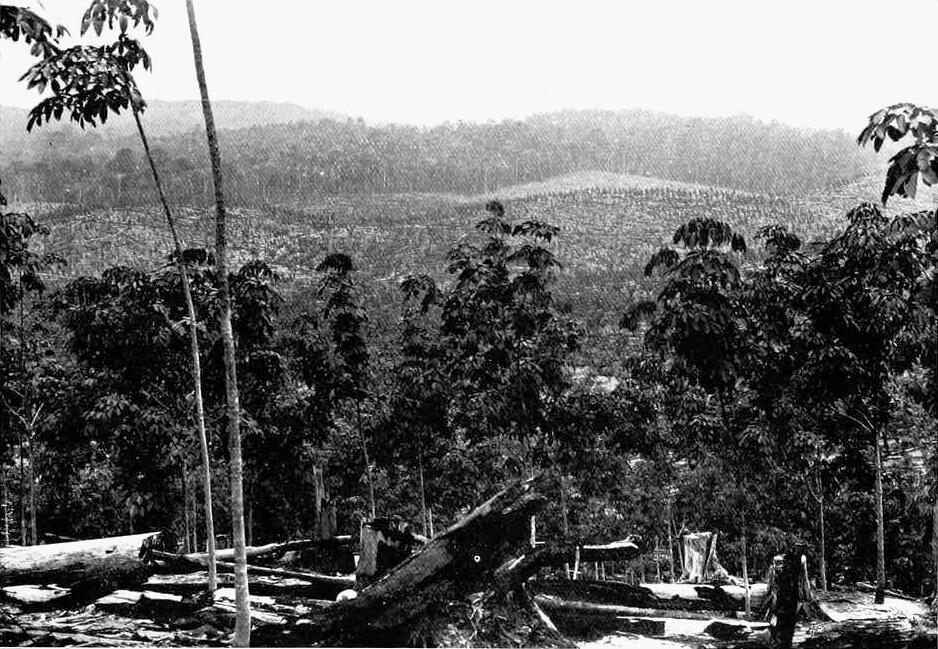

In this chapter I deal with an area of hill land which is malarious when under jungle, or when the ravine streams are choked by weeds after the jungle has been felled. It is equally unhealthy when the jungle has been felled and the ravine streams are free from weeds, for a new malaria carrier appears, namely, A. maculatus. The conclusions reached ten years ago have been confirmed, and much additional evidence could be adduced were it necessary to do so. It will be sufficient, however, if I reproduce what was written in 1909, practically the only alteration being that Nyssorhynchus willmori now appears as A. maculatus.

In the previous chapters I have shown how malaria has disappeared from certain portions of the coast districts of Malaya, as the land has been drained, and the jungle felled. That this often occurs is well known to all with tropical experience; and it is with the hope that this will occur that the pioneer battles with his troubles. The hope is so strongly implanted that he takes it as a matter of course that the health will improve as the land is opened up.

We often hear of what a terrible place some spot was or is. We rarely hear that a place was abandoned on account of its ill-health. But we never seem to hear that a place always remains unhealthy, and never improves as time goes on. This is because after a time the population of an unhealthy place consists almost entirely of those who have acquired a certain amount of immunity. New people have practically ceased to come to it. And so the health seems to improve, and local experience seems to fall into line with the general experience of the tropics. Yet it only wants new arrivals to come in numbers to start a severe outbreak of malaria. I have now, however, to record that in certain portions of the district, there has not been the slightest improvement in the six years during which they have been under my observation, nor have I any reason to suppose they will improve as long as the present conditions favouring the mosquito persist.

| 10.2 |

Anopheles maculatus in ravine streams |

The land to which I refer is the hilly land of the coast districts of Selangor, in the ravines of which run streams of water, often of very small size indeed. In this hill land the mosquitoes which are to be found are A. umbrosus as in the flat land, A. maculatus and A. karwari. Now the important point about these mosquitoes is that, if a ravine stream be kept free from grass and other weeds, A. karwari and A. umbrosus no longer breed in it, while A. maculatus will breed in streams which have been absolutely free from grass and weeds for three years to my knowledge. Extensive observation has shown that it is not in all ravines that A. maculatus can be found, nor is it always present in the same ravine. It is possible there may be some seasonal variation,14 but of this I am not yet warranted in making any definite statement. I can say, however, that no amount of weeding or other care of a mountain stream will abolish A. maculatus, which I have found to be a natural carrier of malaria.

| 10.3 |

Examples of persistence of malaria |

For some years malaria has formed a subject of anxiety to the managers of certain estates in the district, since their labour forces have been seriously crippled, apart from the fact that the Europeans have also suffered severely, and blackwater fever has occurred in one instance. It was always hoped that the general experience would hold good in these estates, and that, as they were more opened up, the health would improve. In the meantime there was nothing to do but to push on with the opening programme, and give quinine to the coolies systematically. This has been done, thereby reducing the death rate and improving the general health of the coolies. The arrival of any considerable number of new coolies was, however, always the signal for an outbreak of the disease, and the older coolies who were apparently becoming acclimatised appeared occasionally to suffer with the new ones.

In the middle of 1907, when my investigations on the estates had for certain reasons suffered interruption, the position was as follows. I had determined the percentage of infected children on many of the estates of the district. I had also determined the adult mosquitoes to be found in the coolie lines, and made certain observations on their breeding places. I had determined that the carrier of malaria on the hill land was A. maculatus, and that it was confined exclusively to the hill land. I had also observed on three estates that it was present when there was grass and other weeds in the drains, but not when these drains were clean. I attributed their absence to the freedom from weeds. I had also determined its absence from certain ravines altogether. I, therefore, concluded that when further opening had taken place, the health of the labour would improve on the hill land places, as it had already done on the flat land places to my knowledge.

In 1908 I was on leave in England, and on my return to Malaya was for several months fully occupied in administrative details of the hospital system, which I was organising for the estates. During this period I came to the conclusion from what I incidentally saw, that despite the lapse of two years and despite the greater areas opened, no improvement had taken place in the hill land estates.

I accordingly determined to investigate the matter de novo. I determined to examine every set of coolie lines in the district and particularly those on the hill land, with the object of ascertaining the exact condition of each. I also decided to make a fuller inquiry into the breeding places and habits of the anophelines. The result of this inquiry has been to show that A. maculatus cannot be exterminated as long as there is water in the ravines in which it can breed; secondly, that malaria is as prevalent in the hill land as before; and thirdly, that quinine in the therapeutic doses can hold in check, but cannot eradicate, malaria.

It will be unnecessary to enter into details of each of the hill land estates, but the following figures will show the general condition.

| 10.3.1 |

Estate “RR” |

This is a large estate, work on which was begun in 1906. From the first, malaria has been prevalent. Quinine was begun in 1906 in doses of ten grains twice a week; but as this was apparently without effect, it was increased to ten grains daily with double doses to those who did not work. Table 10.1 shows the condition.

| 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 61 | |||

| Infected (%) | 73 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 61 | 43 | 174 | |

| Enlarged (%) | 65 | 83 | 49.8 | ||

| Death rate | 73 | 165 | 43 | ||

It should be mentioned that one set of the most unhealthy lines was abandoned in 1908. During 1908 the amount of quinine administered was much less than had been the case in 1907, as ankylostomiasis was said to be the real cause of death in many of the coolies that year. This led to the necessity for giving quinine being questioned, and on my return from leave I found that an entirely insufficient quantity was being given. The dose was at once increased and the result has been to reduce the sickness and the death rate as is seen from the above table.

From Table 10.2 it will be seen that the death rate in 1908 was generally higher than in the previous year. There was no special immigration in 1908; indeed it was smaller than usual; and I attribute it to the idea spread about that ankylostomiasis was the chief cause of the death rate. Quinine was consequently neglected on some estates.

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | ||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 12 | |||||

| Infected (%) | 83.3 | ||||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 12 | 18 | 13 | |||

| Enlarged (%) | 100 | 77.7 | 100 | ||||

| Death rate | 60 | 300 | |||||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 41 | 40 | ||||

| Infected (%) | 37.8 | 12.5 | |||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 40 | 43 | 49 | |||

| Enlarged (%) | 17.5 | 30 | 55 | ||||

| Death rate | 95 | 138 | 176 | ||||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 6 | 17 | 18 | |||

| Infected (%) | 100 | 11.7 | 94 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 42 | |||||

| Enlarged (%) | 83 | ||||||

| Death rate | 200 | ||||||

| Blood examination | Sample number | 6 | 17 | 26 | |||

| Infected (%) | 100 | 23 | 96 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 26 | 13 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 80 | 100 | |||||

| Death rate | 300 | 178 | |||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 13 | 15 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 100 | 100 | |||||

| Death rate | 150 | 56 | 223 | ||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 14 | 20 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 71 | 95 | |||||

| Death rate | 60 | 90 | |||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 18 | 29 | ||||

| Enlarged (%) | 100 | 1 | 100 | ||||

| Death rate | 6 | 58 | |||||

| Spleen examination | Sample number | 15 | |||||

| Enlarged (%) | 100 | ||||||

| Death rate | 260 | 93 | 250 | ||||

The coolies on Division I. of Estate “RR” are housed in three places. The health of these varies, at least the spleen rate varies, being 90.9% in one place, 76.6% in another, and 36.6% about a quarter of a mile from the worst. The majority of the coolies are now living near the last of the three places—hence the lower spleen rate for 1909. It is possible that the mosquitoes which infect the place with the low spleen rate come from a ravine near to the place with the highest. The point is one of the greatest practical importance, but I have not yet finally determined it. In addition, there has been a considerable number of new coolies lately to this division, so the spleen rate is lower than it will be when the recent immigrants have had time to become infected.

The number examined on the other two divisions on this estate were as shown in Table 10.3.

| Division | No. examined | Enlarged spleens (%) |

| II | 63 | 79.3 |

| III | 33 | 75.7 |

An idea of the amount of malaria present will be gathered from the fact that of thirteen children on the estate only two and a half months, no fewer than eight had splenic enlargement.

The death rate of this estate will be referred to later when I deal with the effect of quinine.

| 10.3.2 |

Estate “SS” |

This estate is on the border of the hilly land, and its coolie lines are situated on the end of a ridge. The number of children examined was thirteen and the spleen rate 30.7%. Five of these children had been only one month on the estate, so the corrected rate would be fifty.

| 10.3.3 |

Estate “TT” |

This estate lies on the edge of the hills with part on the hills and part on the flat. The lines at the west end are close to jungle now being opened and on the flat; the central lines are on the flat about half a mile from the nearest jungle; while the east lines are among the ravines, but ravines which are clean. Anopheline larvae were found only a quarter of a mile from these lines in a clean ravine. No larvae were found in two ravines close to them. Sinniah’s lines are about a quarter of a mile from rather poorly drained native holdings. The spleen rates observed on this estates are summarized in Table 10.4.

| West Lines | Central Lines | East Lines | Sinniah’s Lines | |||||

| Year | No. examined | Rate | No. examined | Rate | No. examined | Rate | No. examined | Rate |

| 1906 | 14 | 64 | 28 | 32 | 5 | 57 | 17 | 35 |

| 1909 | 49 | 51 | 47 | 17 | 31 | 45 | 8 | 37 |

I should say the east lines of 1909 were on the same range of hills, but not on the same spot, as those of 1906, which had to be abandoned on account of their ill-health. The figures are, therefore, not comparable as expressing the condition of health of the identical places, as the other figures do throughout the book. The figures, however, show that this estate is in much the same condition as it was. The central line spleen rate of 1909 was affected by four new arrivals from an estate whose spleen rate is about 50, otherwise it would have been 9.3%, which would be in agreement with the rate generally found for the distance the lines are from a breeding place of anophelines. Table 10.5 summarizes the spleen rates and the death rates of Estate “TT”.

| 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | |

| Number examined | 67 | 135 | ||

| Spleen rate (%) | 41.7 | 37 | ||

| Death rate | 48 | 86 | 64 |

From the figures in Table 10.2 it will be seen that on the other estates in the hilly land there has been no improvement in the amount of malaria, as indicated in the spleen rate during the years I have been observing them. The death rate has varied, but this, as I shall show, has been due to quinine administration.

These figures show in the most unmistakable way that there has been no improvement in the health of these estates. They indeed only confirm what I had already observed from the hospitals, from visiting the estates, and from the health of the Europeans.

| 10.4 |

What is a hill? |

On one occasion I visited Lanadron Estate. On the flat river bank the spleen rate was low and the children were healthy. Further in, at the “Darat Lines”, no fewer than 17 out of 27 children (62%) born on the estate had enlarged spleen. The “Darat” is about 23 feet above the general level of the surrounding flat land, and might have been, at one time, a sand bank in the sea. Yet in the eyes of A. maculatus it has found favour, and to them, at least, it is a hill. At the time of my visit I searched for them in vain, but Dr. Rattray afterwards found them in abundance.