| 11 |

The effects of malaria |

The time was towards the end of July last year: scene, the hill above Minehead in the county of Somerset; dramatis personae, the author and his two youngest sons on horseback. The school term had ended the day before; this was the start of our long-talked-of riding tour on Exmoor. The sky indicated perfect weather; it was one of the glorious mornings that England sometimes vouchsafes her long-suffering people. Below was the Bristol Channel; across it were the Welsh hills. Dunkery looked down on us from the south. The Metropole Stables had mounted us excellently, and as we settled into our saddles for the 20-mile ride through Selworthy, Porlock Weir, and Ashley Coombe to Lynton, we talked of many things—but not of malaria. That was a thing forgotten. We were living a life where it played no part. Ten thousand miles away was the Malay Peninsula, its fever and its jungle. The purple heather was under us, the horses were keen, and away we went.

And as we travelled we fell into conversation with a gentleman trying a hunter. Inadvertently I used the word “syce”. As a touch to a secret spring, or the “open sesame” of the immortal tale, the doors of the East rolled open, and we talked of far-off lands. Although long retired from business, he had lived in Calcutta for many years, and he still had interests in the Malay Peninsula. One estate, to which he referred, I knew by repute as very malarious, although I had never been there; so I asked him about it, without indicating my profession. And he replied that it was just like so many other tropical ventures: “You start in gaily expecting great gain; but somehow fever strikes it in the first year, and before you know where you are, you have spent double the estimate.”

A true saying, as we shall see from what I wrote ten years ago; nor need I add to it.

| 11.1 |

Effect of malaria on the Europeans |

During the years I have known this district, I am talking now of hill land, only two Europeans have been known to escape the disease. They lived on a spot where the spleen rate is only 20. It is the place which is farthest from the breeding place of anophelines, being on a point well away from any ravine or jungle. That such a spot should be found so near to very unhealthy places is of the most hopeful augury, showing that the flight of the hill-land mosquito is by no means great.

There are at the present moment twenty-nine Europeans living on ten hilly land estates. Of these twenty-five have had malaria at some time or other. Of the four who have not had the disease, two have been less than one month on the estate; one takes 15 grains of quinine daily; one has been six months on the estate without getting the disease.

As I write I have a record of the Europeans who have been on these estates during the past four years. It shows how practically all have had the disease, how from time to time they were invalided either to hospital, or off on sea-trips to recover their health, or to Europe on long leave. It shows how many have left the estate permanently, unable to withstand the disease. One man who had suffered severely from malaria had blackwater fever, but fortunately recovered. There is only one bright spot in the record; it is, that no European has died from malaria.

So much sickness among the Europeans means that they cannot supervise their work properly; and if there be much sickness among the labour force at the same time, the absence of the controlling and directing force of the estate is, indeed, deplorable. Few native subordinates can be trusted to see that quinine is properly administered to a labour force, and one of the great troubles is that, if the manager from sickness cannot supervise it, the subordinate is very liable to do this duty in a perfunctory way. The welfare not only of the estate, but of the labour force, depends, therefore, on the well-being of the manager.

| 11.2 |

Effect of malaria on the coolies |

No less severely has malaria affected the coolies. In visiting estates I have always noted all cases of sickness seen in the coolie lines; in addition I have noted on the opposite page of my book any general observations which might seem of importance. I have, therefore, a fairly complete record for some years of the health of the estates which have been under my care. From this book I will give the substance of a few notes showing the effect of malaria.

On one estate 170 coolies were recruited. They refused to take quinine at first, and were a somewhat unruly gang. Within two months of their arrival I visited the estate and found that on the day of my visit 102 out of the 170 were unfit for work. Many of these were removed to hospital. A month later I note, “Of the gang of 170 only 57 remain on the estate. Of these 29 working, and 28 off work.” Practically all these coolies were lost to the estate.

Of another estate: “Have been having a bad time with malaria—turning out 170 out of 340 coolies.” The following month turning out 179 out of 250 coolies. The following month again, the note is “150 coolies.” In other words the coolies had either given notice and left or absconded. On this estate the labour force was reduced in three months from 340 to 150. I need hardly say that weeds got a firm hold of it.

Another estate: “Have been very bad with fever, practically every coolie had it, and about six deaths. Appear to be getting it in hand with quinine. 140 coolies working out of 350.” The following month, “turn-out 150. Coolies looking better.” A month later the manager remarked, “turn-out somewhat better but accounts not made up.” The manager had been very ill. He was taking infinite pains with quinine administration. He had every room in his lines numbered and the name of every coolie who lived in each of these rooms, in a special book.

He tried to get every coolie twice daily, and ticked off in his book when each coolie had received his quinine. Only those, who, from visiting coolie lines, know how difficult it is to account for each coolie on an estate can estimate how much labour this meant.

Another estate: “19 cases of malarial dysentery. The manager had not given quinine when complaint was dysentery. Every one gave a history of fever five to ten days previously. Are getting a considerable amount of quinine. Seventy-five out of 190 working.” A month later I note, “Now only about 80 coolies on the estate. Others wish to leave, but — and — and — persuaded them to stay for two months. Many have died in hospital.” I promised that if they would take their quinine regularly and would report at once to the manager when ill they would not die. New lines were also built for them in another place. A month later I find less fever on the estate, and note, “old lines abandoned, coolies healthier.”

Among the children malaria is no less severe. On one occasion I was asked by a manager to advise him what could be done for the children, as 15 children had died in the previous two months out of a total of 33. He told me a native clerk was giving them quinine daily. I examined the blood of the remaining 18 and found parasites in 17 of them. Such a terrible death rate among the children affects the mothers of the estates and leads to loss of labour, since the coolies naturally refuse to live in such unhealthy estates.

I have been struck by the small birth rate of malarious estates, including those on which quinine is given. I have had no opportunity of investigating this, but inquiries are now being prosecuted. It has been said that quinine may have some injurious effect in reducing the birth rate. I am unable to express any opinion on the matter. I am indebted to the late Mr. E. V. Carey for the following:

Notes of Fever experienced upon New Amherst Estate.

Between the years 1892 and 1898 there were on an average over 50 Tamil women upon the check-roll each year. Yet in the whole period no living child was born. Several women became pregnant, but only in one case did the child become quick, and even in this case the woman eventually had a miscarriage. The estate was so riddled with malaria that the coolies were all miserably anaemic and lacking in strength. So anxious was the management that the stigma attached to the absence of child-birth should be removed, that every possible care was taken of the women when they became pregnant; light but regular work being provided for them, and a supply of milk, etc., being given them; but all with no result, although a big present was offered to the woman who first brought forth a living child, and the coolies were all most anxious themselves that this reproach should be removed.

The supply of cooked rations to all coolies under the supervision of a high caste cook worked wonders in improved health and general physique, but when the coolie insisted in returning to the system of feeding himself there was soon a relapse, and the estate had eventually to be abandoned. During the last two years, at least, all coolies were given a 5-grain pill of quinine each morning at muster, together with a cup of hot coffee.

This is very striking evidence of the effect of malaria on the birth rate, of the practical inutility of small doses of quinine in intensely malarious spots, and of the difficulty, indeed impossibility, of carrying out the most beneficent measure in the face of native opposition and prejudice.

The effect of the introduction of any large number of new coolies to estates of such an unhealthy character, as those I am describing, can be estimated from the following extract from my annual report for 1906, quoted in the Selangor Administration Report for the same year.

The great increase in the death rate has been due to the introduction of a very large body of Tamil coolies, and the spread among these of malaria, mostly of the malignant type. These coolies came mainly from famine districts in India, and while of a fair average physique for recruits, naturally do not compare in their capacity of resistance to disease with coolies who have been well-fed and well-housed for a year on the estates here.

Among these coolies malaria spreads with extraordinary rapidity, and the systematic doses of quinine, which were sufficient to maintain the older coolies in health, appeared to have little effect on these. Within two months, it is hardly an exaggeration to say that 90% of these coolies in the Batu Tiga district were infected with the disease; and the children suffered with equal or greater severity. From the new it spread to the old coolies, and also to the Chinese and others working on the estates draining and building lines. Among the Chinese, who will not take quinine, it was very fatal, and many of them were brought to the hospital in a moribund condition. The new coolies literally made no stand against the disease, and on some estates there was difficulty at first in inducing them to take quinine.

Another fruitful cause of death was the bowel trouble, which so frequently supervenes on an attack of malaria. In the hospital in the month of December, out of forty-seven deaths due to malaria, no less than thirty-four were the result of bowel complications. These patients rarely complain of fever; and it is only by microscopic examination of the blood that the malaria element in the case is detected. At first the necessity of giving quinine in addition to other treatment was not recognised on estates, as the coolie made no complaint of fever, and the consequence was that many new coolies, with no stamina to spare, so to speak, were literally past hope in three or four days.

As I had occasion to point out a year or two ago in a paper on quartan malaria, patients with dropsical swelling resulting from malaria are often unaware they have malaria, even when the thermometer shows they have a temperature of 102°F, and their blood is swarming with parasites. As if further to confuse the issue, many of the new coolies rapidly became anaemic and dropsical from the malaria, and attributed their illness to everything but the right thing. In some cases malignant malaria was worthy its name, and struck dead those who forty hours before had been at work. It ultimately became obvious that the only way to save the coolies was by daily administration of quinine to every coolie on the estate. This is now being done on eight estates with an aggregate labour force of about 2000 coolies, and fortunately there is some evidence that the coolies begin to appreciate the value of the drug, at least there is now no opposition to its administration.15

| 11.3 |

Variation of death rate with spleen rate |

The important influence which malaria has on the health of an estate will be more easily realised from a study of the relationship existing between the spleen rate of the estates obtained from my examination of the children and the death rates taken from the Indian Immigration Report for 1908.

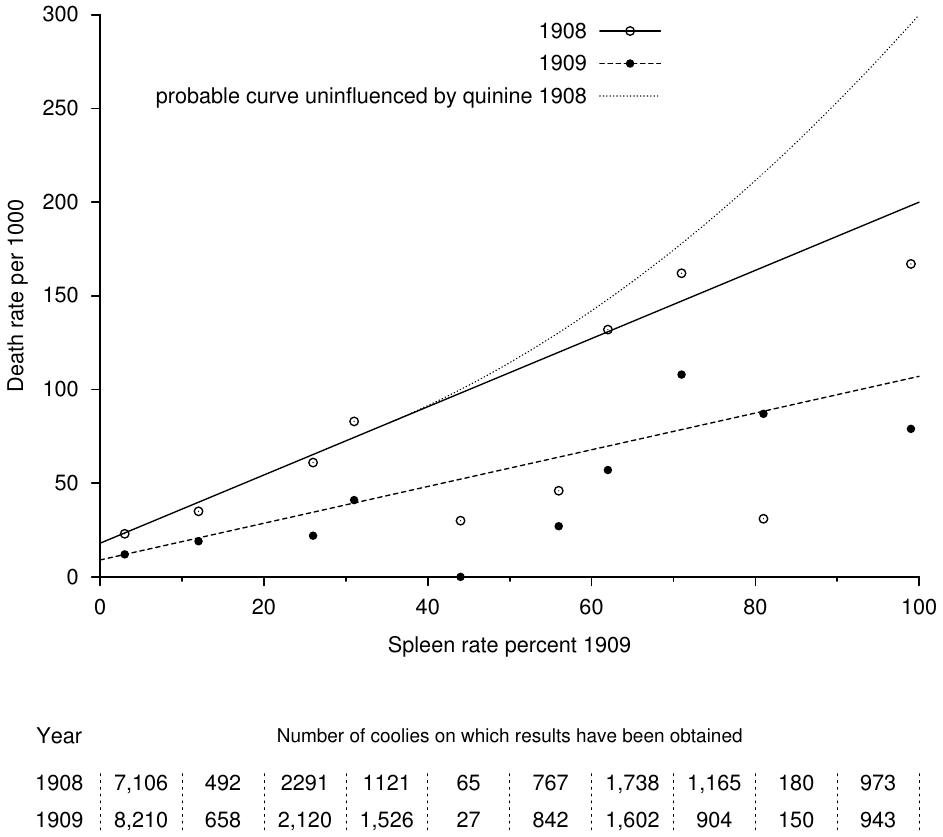

Table 11.1 shows the death rates of the estates arranged in accordance with their spleen rates. It shows the total population living on estates where the spleen rates varied from 0 to 100%, the total number of deaths in, and the death rates of, these populations. These figures exhibit the terrible effects of malaria, and I have exhibited them in graphic form in Figure 11.1.

| Spleen rate (%) | Populationa | Number of deaths | Death rate (‰) |

| 0–10 | 7106 | 175 | 24.6 |

| 10–20 | 492 | 18 | 36.0 |

| 20–30 | 2291 | 143 | 62.4 |

| 30–40 | 1121 | 90 | 82.0 |

| 40–50 | 65 | 2 | 30.0 |

| 50–60 | 767 | 35 | 45.6 |

| 60–70 | 1738 | 232 | 133.4 |

| 70–80 | 1165 | 189 | 162.3 |

| 80–90 | 180 | 6 | 34.0 |

| 90–100 | 933 | 163 | 167.5 |

- a

- In the original text, the column heading reads “Average population”. However, the absolute and per-mille death rates make it clear that these numbers give the cumulative population in each category (M.P.)

From [a spleen rate of] 0–40%, the influence of malaria is unaffected by systematic quinine administration, except in the case of one estate, “S”. From that onwards it is given with varying degrees of thoroughness. I think it not improbable that, although it has been possible to plot the lower values as a straight line, that from the point at which quinine begins to influence them, the values, if uninfluenced by the drug, would be represented by a curve rising to about 300‰. It is difficult to believe that the considerable doses of quinine given to a population of 1165 on the estates in the 70–80% group should have had no effect. The death rate of several estates, whose spleen rate is between 90 and 100%, ranges between 200 and 300‰.

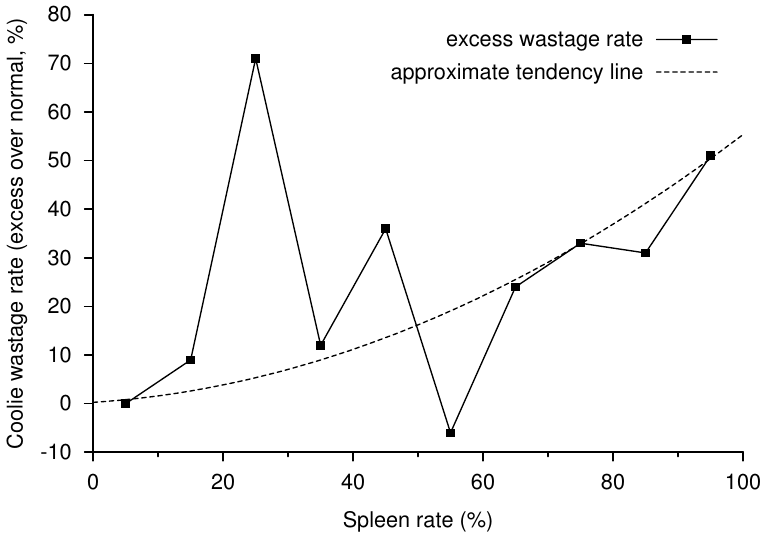

As will be seen from Figure 11.2, the greater the amount of malaria the greater the wastage from all causes. To maintain labour forces on the more unhealthy estates at a constant strength, larger proportions of the coolies would be new; and the death rate of these would be higher than that of the older coolies. Among the more unhealthy estates there would thus be death rates increasing at an ever-accelerating rate. I do not think 300‰ would be the maximum in a locality of the most intense malaria were the labour non-immune.

The values which are plotted below the straight line are known definitely to be the result of quinine to a great extent. Between 40 and 50%, the low death rate is due to all the coolies (65 in number) on one estate having been dosed daily with 10 grains of quinine, and once a week with castor oil. The low death rate on the estates, whose spleen rate was between 50 and 60%, was due to two of the estates using quinine, one in the most thorough manner possible. The same applies to the low death rate with the spleen rate from 80 to 90%.

The plotting of the death rate values shows in a graphic manner not only how malaria is responsible for most of the deaths on the estates, but enables us by extrapolation to arrive at the conclusion that were malaria eliminated the death rate of the Tamil population on an estate would be about 15‰. [1919.—We now know it would be under 10‰.—M. W.] The line shows, too, how money can be spent with most profit and advantage in improving health on a malarious estate.

The sum of money which would be required to reduce the deaths from causes other than malaria by 3‰ would in all probability reduce the deaths from malaria by 100‰, if spent on anti-malaria works. It is absurd to talk of applying to malarious estates the sanitary measures which are required in an overcrowded town, and expect them to improve its health. Expenditure on such measures would only be an obstacle to expenditure on the special sanitation required by the local conditions. As will be seen later, sanitary areas free from anophelines should be established on malarious estates, and the coolies housed on those areas.

| 11.4 |

The Death Rate uninfluenced by Quinine |

| 11.4.1 |

Public works |

Those who have seen the terrible death rate on public works in the Federated Malay States, such as the Ampang and Ulu Gombak Water Works of Kuala Lumpur, the Ayer Kuning Water Works of Klang, the Changkat Jong Water Works of Teluk Anson, the Ayer Kuning railway tunnel near Taiping, will readily believe, I think, that a death rate of 300‰ is no exaggeration. As Daniels says, “under such circumstances in Malaya, malaria is as severe and prevalent as in bad parts of Africa.”

| 11.4.2 |

Estates |

From what I have seen on the estates under my care, and from what I have gathered when travelling through the Federated Malay States, I have come to the conclusion that malaria is the chief factor in the death rate of estates. It is entirely in keeping with the observations I have made, that of twenty-one places of employment, whose death rate was over 200‰ as given in the Indian Immigration Report for 1908, no fewer than eighteen of these should be estates in hill land, and of the three exceptions, two were estates whose coolie lines were close to jungle. I have no information as to the third.16

The average labour force employed on these places was 2130, and the average death rate was 280‰. On some of these places quinine was certainly given, though probably not very thoroughly; but on the majority I believe it was not given systematically to the whole labour force. Cholera, plague, and smallpox were not present to swell the death rates.

| 11.4.3 |

India |

Perhaps to those not acquainted with what malaria can do, the following extracts from the Proceedings of the Imperial Malaria Conference held at Simla in 1909 will give some idea of how great an effect this disease may have on the death rate:

During the two months of October and November the number of deaths recorded in the Punjab as due to fever was 307,316, as against less than 70,000 in both 1904 and 1905, and less than 100,000 in 1907.

Studied in more detail, the ravages of the epidemic in these areas where it was most intense are more apparent. In Amritsar the mortality for many weeks was at the rate of over 200‰.17 In Palwal the mortality rose to 420‰, and in Bhera to 493‰. Curiously in Delhi, a notoriously malarious town, the death rate rose to only 149‰. But a closer examination of the statistics shows that parts of this town were much more seriously affected than one would judge to be the case from the statistics of the whole city; in Ward I., for example, the mortality rose to over 300‰.

The death returns of Amritsar show that the densely crowded outer portions of the city were mainly affected. Again, in these the mortality was higher than the figures for the whole city would indicate. In Division IX., for example, with a population of 17,206, the death rate rose to 534‰, and for six weeks was over 400‰.

In the district returns, with the exception of those relating to the Gurgaon district, which show among a population of 687,199 a death rate of 267‰, the mortality rates are not so high as those given for the towns. This might be taken as showing that the mortality was greater in towns than in rural areas, but a study of returns from individual thanas and villages modifies this conclusion, both thanas and villages frequently showing mortality rates during October and November of 300, 400, or even 500‰.

I think, therefore, that the curve of the death rate uninfluenced by quinine as I chart it, is a close approximation to the truth. It is based on the maxima of the death rates and is certainly no exaggeration.

| 11.5 |

Wastage of a labour force |

Although local factors have a powerful influence on the happiness and welfare of a labour force, it can easily be understood that where an estate is unhealthy, coolies will be less contented and will be less inclined to stay. A month’s notice frees a coolie on the estates of Selangor, and in many instances he leaves without giving even the legal notice. There is no indentured labour.

The chart in Figure 11.2 illustrates how on the estates under my care the wastage of labour from all causes has a very definite relationship to the health, as exhibited by the spleen rate.

I have taken, as the base line, the wastage on the estates having the lowest spleen rate; and the other wastages have been calculated as a percentage above or below this. The chart shows that the greater the spleen rate the greater the loss of labour. There are only two exceptions. The very great loss on estates whose spleen rate was from 20 to 30 was due to practically the whole of the coolies on one estate leaving, owing to the conduct of a drunken mandor. The Government Immigration Report deals with this. Great loss was due on another estate to differences between the coolies and the manager. These are exceptional circumstances, and this group of estates showed a wastage in 1907 quite in line with that of other estates.

On the group of estates, whose spleen rate was 90 to 100, the actual loss was 507‰. In other words, while the coolies remain on an average three years on the healthiest estates, they remain only two years on the most unhealthy estates. The extra year means, for the healthy estates, an increase of the labour force by 50%, and more than a 50% increase in the work done; for the coolie at the end of his two years is a skilled workman, especially where he is tapping. Malaria is, therefore, an economic factor of great importance.

| 11.6 |

Economic effects of malaria on the estate |

In the working of an estate, a certain number of coolies are required for each class of work, and the manager must estimate some months before how many he will require, so that the necessary number may be recruited from India in time for the work. Any extension of the estate necessitates more coolies. One of the most important works of an estate is weeding. In a tropical country like this weeds grow with surprising rapidity; in less than two months they will form in many places a complete cover to the ground, and having seeded, it will take months to eradicate them. In addition, a grass called lalang often takes root, as its seeds are blown to great distances by the wind. The roots of this grass grow several feet deep, and to eradicate it costs $50 an acre at least.

The most economical method of working an estate is to have a labour force of such strength that the whole estate can be weeded once in from two to three weeks. Not a weed then has time to seed, and the cost of weeding falls to about 50 to 60 cents an acre.

If, then, there are too many coolies on an estate, the work will be insufficient for them, which will lead to dissatisfaction; while, if there are not sufficient coolies, the work gets behind, and if this work be weeding, then the whole estate may be covered with lalang. As the cost of bringing an acre of rubber into bearing is generally estimated at about $250, it will be seen that the effect of an outbreak of malaria, which seriously cripples a labour force even for only a few months, may easily increase the original cost of an estate by 20%, and on an estate of 1000 acres will actually cost about £6000 sterling.

The foregoing was written at a time when the estates were being developed, and the chief problem was to prevent them being overgrown by weeds and ultimately smothered by the jungle.

Later, when the heavy shade of the rubber trees removed anxiety on that score, the shortage of labour made it difficult to tap the trees and collect the rubber. Indian labour being unequal to the task, Chinese labour at a much higher rate of pay had to be employed. How much extra the cost was will be found at the end of Chapter 15 on Seafield Estate.