| 2 |

Town of Klang from 1900 to 1909 |

| 2.1 |

In 1901 |

This town, the headquarters of the district of the same name, is situated on the Klang River, some twelve miles from its mouth, and five miles as the crow flies. In 1901 the census of the population showed there were 3576 inhabitants, occupying 293 houses. Since then the town has greatly increased in density of population as well as in area. Within the old town limits of 1901 the number of houses has increased from 293 to 468, which would give an estimated population of 5745. This, I believe, will be found to be less than the actual increase of the population. In all subsequent statistics when comparison is made between the figures of different years it is to be understood that these figures refer only to the population within the town limits of 1901, and not to those of the present town limits. The old town limit was practically the Jalan Raya, except where for three-quarters of a mile this road ran parallel with the river, and the river was the boundary.

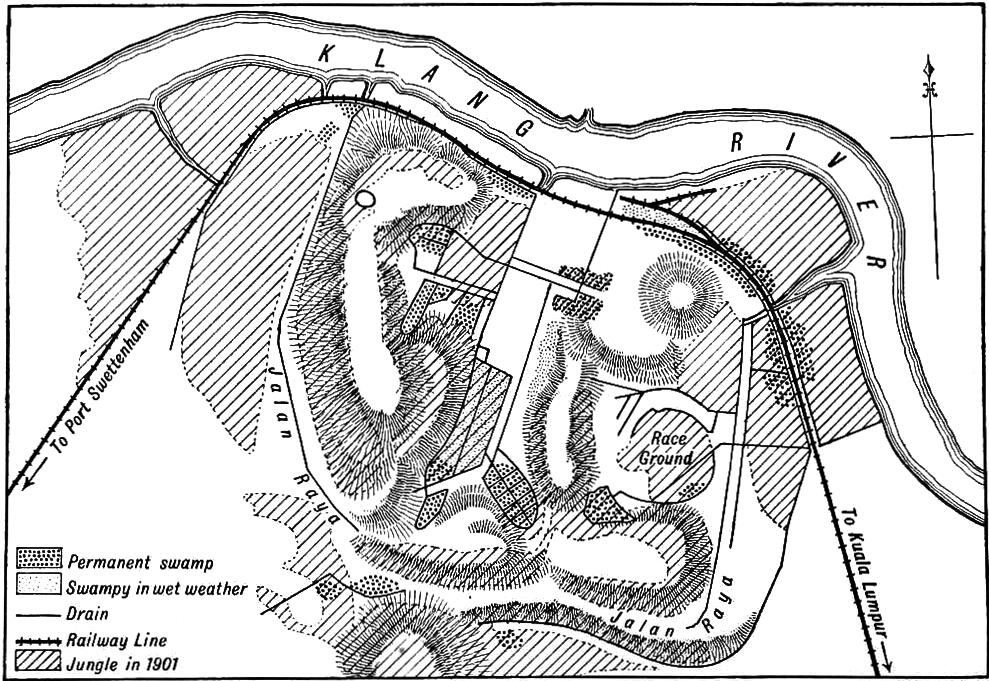

The area of the town was in 1901 approximately 290 acres. Of this 22 acres was swamp, 25 acres virgin jungle, 60 acres dense secondary growth in many places 30 to 40 feet high (see Figure 2.1). The distribution of these undesirable portions will be seen from the map. The whole town was permeated with their influence, and it is hardly surprising that malaria was a scourge.

Assuming duty early in January 1901, as Government Surgeon of the Districts of Klang, Kuala Selangor, and Kuala Langat of the State of Selangor, one of the Federated Malay States, I found the hospital at Klang full of malaria. It appeared to me that my duty consisted in doing more than remaining in hospital all day treating patients, since to this there could be no end, if steps were not taken to prevent infection of the population. At that time, Ross’s brilliant discovery had been fully confirmed by the Italians and others. Manson’s [3] dramatic proof at Ostia and at London left no doubt of what could be done under certain conditions. Ross himself had favoured mosquito reduction, and was actively engaged in West Africa in putting this method to the test. The Italians [4] were rather in favour of mechanical prophylaxis by mosquito netting, and by the use of quinine; and Koch [5] had already reported a success in a small community by the regular use of this drug.

At this time nothing was known about the species of anophelines, and the valuable reports of the Commissioners of the Malaria Committee of the Royal Society [6] bearing on the importance of species were not published until the year after the work at Klang had been begun.

| 2.2 |

Choice of anti-malarial method |

At Klang the work of eradicating malaria seemed well-nigh hopeless. No hot or cold season even temporarily stopped the mosquito pest; and every well, ditch, and swamp teemed with larvae. The active cooperation of the native community could not be expected; and active resistance, especially from the Chinese, was certain if any attempt was made to enforce the use of quinine. Then enforcement of mosquito nets was, of course, impossible; since this would have meant constant house visitation at night. Compulsory screening of the whole of every house was equally impossible for financial reasons; nor would people have remained within mosquito-proof houses in the evening, which is so pleasantly cool after the heat of a tropical day. Again, with an area so extensive, subsoil water so high as to form permanent swamps, and aquatic vegetation so dense, the sweeping out or dealing with the individual collections of water in any continuous manner was impossible. As surgeon of a district fully 100 miles long, I felt that the time I could devote to any anti-malarial measures would be limited, and I also felt that no other member of the community was at all likely to be willing or able to give more time than myself to the supervision of measures which would keep down mosquitoes only as long as they were constantly applied. And to be quite candid, knowing that the burden would fall on myself, I did not quite appreciate the idea of having constantly to stand in the sun supervising coolies and insisting on the thoroughness on which alone success would depend.

Considering all these elements of the problem, I rejected as impossible Koch’s quinine method, and the Italian mechanical prophylaxis, and decided to recommend Ross’s method of mosquito reduction. To suit the local conditions, I determined that any expenditure should be on works of a permanent nature. By draining and filling, there would be a large and permanent reduction of the breeding places of mosquitoes; and presumably malaria would be correspondingly reduced.

| 2.3 |

A fortunate choice |

As time has shown, it was indeed a fortunate choice. It has been successful far beyond our expectations. No other method would have been of any real value; nor would any of them, or even several of them combined, have given anything like the results obtained by this. It is easy to see, too, that some of the failures to control malaria in other countries, reported in later years, were due to those in charge not adopting the radical method; or, where it was attempted, not carrying it out with sufficient energy and on a large enough scale.

It was a fortunate choice from another point of view. Although our first efforts were on a small scale in a town, its immediate success induced me to consider the possibility of extending the method to rural areas; and in these, too, the results have been not less successful in many places, as this volume will show. Although the details have required modification to suit the particular habits of the species of Anopheles we have encountered, the radical method of mosquito reduction has everywhere given results superior to any other, even among the small populations to be found in plantations and villages.

Although the success was due to a fortunate choice of the method adopted, as it turned out, there was a real stroke of luck, not recognised until many years after. It was this: Had the hills of Klang been higher, or had Klang been situated in the main range of hills, instead of being practically an island in the Coastal Plains, the clearing away of jungle from the hills and the draining of the valleys and swamps would have led to the introduction of a new malaria-carrying Anopheles, certainly not less terrible than the one we got rid of by our drainage. Instead of success there would have been complete failure; and there can be little doubt anti-malarial work would have been set back for years in the Federated Malay States. Indeed we escaped very narrowly from this peril. For at the very moment my scheme for the drainage of Klang reached Government, a proposal to test Ross’s new theory was received from the then State Surgeon of Negri Sembilan. He suggested that if he were given the requisite staff, he would make full inquiries into the incidence of malaria in the town of Seremban and the mosquitoes there. After the records were complete, an attempt would be made to eradicate the mosquitoes, and the results recorded. Now Seremban is a town among the hills of the main range; so there is every reason to believe from my own experiences in similar places the experiment would have been a complete failure. Fortunately my scheme was sent in with full details of the incidence of malaria in Klang, of the houses infected, of the mosquito breeding places, and of the urgent need for action. The case for carrying out an experiment in Klang was overwhelming. It won the day; and much more than that, as the years were to show.

Finally I must confess that I by no means expected the success, which as a fact followed the works. I had the feeling that perhaps a 20% or 30% reduction might be obtained in the hospital returns. At times a feeling of despair came over me. Although I can afford to laugh at it now, one portion of the railway line between Klang and Port Swettenham always recalls to my mind the feeling of despair which came over me there one day, at the height of the outbreak of 1901. How was it possible to eradicate a disease like malaria, when those infected were liable to relapses for years, and at each relapse be capable of infecting others if any Anopheles at all were present? Then there was the danger of infected people coming from other parts keeping up a constant supply of malaria. Indeed I was prepared for a total failure of the works, and had my answer already prepared should I be called to account by Government. It was that Ross had proved anophelines did carry malaria; that to remain doing nothing was to remain to die; and that it was at least worth spending money to try whether such a scourge could be removed or even reduced. I record these feelings that they may encourage others who may be dissuaded by the apparent magnitude of the task from attempting to combat this disease.

| 2.4 |

Preliminary steps |

Although the extreme prevalence of the disease was apparent to me from seeing so much of it in the hospital, some definite statistics were required if Government were to be justified in spending money. And as a business transaction it was also necessary to obtain some knowledge of the then condition of the town for comparison with subsequent periods after the works had been undertaken, to determine whether the results were worth the expenditure. Unfortunately, although there were many cases of malaria in the hospital (they had in fact formed 24.9%, of the total admissions for the previous year) there was no record of the residence of the patients beyond the district in which they lived. And, although there had been much sickness among the Government officers, no record existed of the disease from which they had suffered, although numerous prescriptions for quinine probably supplied a very significant hint. From the death register little help could be obtained since the only qualified practitioner in the district was the Government surgeon, and only such deaths as were certified by him could be advanced as being assigned to their true cause.

My first care was, therefore, to put the record on a more satisfactory footing. The exact residence of every case of malaria admitted to hospital was carefully and personally inquired into by me. This was very essential, since the patients, if casually asked where they lived, generally answered Klang, although in fact they might have lived miles beyond the town limits. But for these precautions the returns would have exaggerated considerably the actual amount of malaria in the town. To widen the basis of the statistics, I had new returns prepared showing the number of out-patients treated for malaria. The disease for which an officer obtained sick leave was recorded; and for some months I personally kept a register of the houses within the town which were infected with malaria, at the same time recording the number of cases which occurred in each as they came to my knowledge.

These precautions I maintained until I went on leave early in 1908. Subsequent changes in the staff led to these being overlooked, and only recently I discovered that it was so. The record has again been put on a satisfactory basis; but unfortunately the returns for the years 1908 and 1909 on this account are not available for comparison with previous years. Fortunately the blood and spleen census of the children is a record of the condition of the town not affected by hospital statistics.

| 2.5 |

Anopheline breeding places1 |

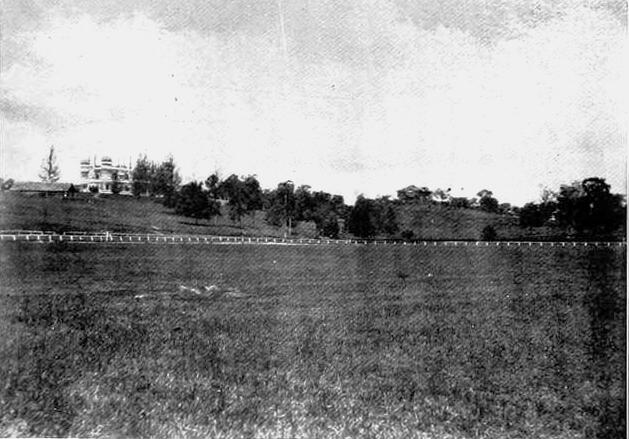

These were found everywhere within the town, and a plan was prepared showing their distribution. In the very centre of the town a swamp existed, with houses close up to it. People have told me they shot snipe on it from the Rest House. As will be seen from the map the town is situated within, upon, and around, a somewhat semicircular group of small hills. At the foot of the hills, especially where they bend to form small valleys, the ground water was so high as to form permanent swamps. In the absence of a town water supply, wells innumerable were found, mostly teeming with anopheline larvae.

The exact species were not determined for some time after the works had been started, but even then some of the original swamps had been completely drained. In December 1903 and January 1904, Dr. G. F. Leicester investigated the anophelines of Klang and reported as follows in his Culicidae of Malaya [7]:

The jungle on the hill range running parallel with the Langat Road was entered at several points to ascertain what mosquitoes were common there. On the first occasion Myzorhynchus (Anopheles) barbirostris and Mansonia annulipes were obtained in very large numbers during the day, but on the hill marked M on the map, no Anopheles were obtained in the evening though they were abundant in the day. Later on the jungle was visited on two other occasions, and the number of Anopheles present had considerably diminished.

There is evidence that great seasonal variation of the number of Anopheles in the jungle occurs, as on an unknown date last year Mr. E. V. Carey observed Anopheles in great numbers in the jungle at the third mile; on a later occasion he, with Drs. H. E. Durham and Watson, visited this jungle, and they were unable to find a single Anopheles.

| Environment | Stage | Species |

| caught in houses | adult | Myzomyia rossi |

| Cellia kochii | ||

| Myzorhynchus karwari | ||

| caught in jungle | adult | Myzorhynchus umbrosus |

| Myzorhynchus sinensis | ||

| mud holes (hoof marks or wagon ruts in a road) | larvae | Myzomyia rossi |

| Cellia kochii | ||

| rain puddles | larvae | Cellia kochii |

| swamps | larvae | Myzorhynchus barbirostris |

| Myzorhynchus sinensis | ||

| Myzorhynchus umbrosus | ||

| Cellia kochii | ||

| marshy ground fed by a stream | larvae | Nyssorhynchus nivipes |

| Cellia kochii |

The disappearance of the mosquitoes does not seem to have any relation to the rainfall, nor should I expect this, as the swamps at the foot of these hills where larvae were found are permanent, and therefore the breeding places would not dry up during the season.

Dr. Leicester’s findings on anopheline breeding places at Klang are summarized in Table 2.1. I think there is a possible mistake with regard to the Myzorhynchus which was found by Dr. Leicester on the hill. My recollection is that he called it at the time umbrosus. In his Culicidae he calls it barbirostris. I think the explanation is to be found in the existence of another Myzorhynchus so closely allied to umbrosus as to be possibly only a variety. It differs from M. umbrosus in having two costal spots, the basal of which is very small. I think, therefore, that Dr. Leicester when he came to go over his specimens in Kuala Lumpur rejected it as umbrosus on account of the two costal spots, and so called it barbirostris. I call this variety in the meantime Myzorhynchus umbrosus. I am the more disposed to think this is the true explanation of the change of name, as Myzorhynchus umbrosus is the common jungle Anopheles, and I have found it universally in jungle here. Not only so, but I have found it in enormous numbers. On the occasion when Dr. Leicester visited the hill, the mosquito was in such numbers that simply by slipping a test-tube from one part of our clothes to another, six or seven mosquitoes could be obtained in perhaps about two minutes. Dr. Leicester, myself, and an attendant caught something like two hundred anophelines in a quarter of an hour, and simply could not stand the biting further. I may mention that Mansonia annulipes, Desvoida jugraensis, and Verallina butleri were present in considerably greater numbers than the anopheline, so it can be imagined a quarter of an hour in that jungle was unpleasant. It is of sufficient interest to record, that although Myzorhynchus umbrosus was swarming in the jungle and attacking during the day, in a rubber estate separated only by a 20-feet road, but, of course, free from undergrowth, we were entirely free from attack, and no adults could be seen.

The point of the presence of this anopheline is important, as I have found it to be a natural malaria carrier. Of ten adults taken from coolie lines on Estate “T,” one was found with numerous zygotes and sporozoites.

The anophelines found in Klang Town in 1909 are listed in Table 2.2.

| Pseudo-myzomyia rossi? [sic] var. indefinita |

| Cellia kochii |

| Myzorhynchus barbirostris |

| Myzorhynchus sinensis |

| Myzorhynchus separatus |

The last of the breeding places where Nyssorhynchus nivipes and Nyssorhynchus karwari were found was destroyed about 1904, and except for the renewal of a small piece of one of the swamps in 1908 through a brick drain being put at too high a level, there is now, 1909, in Klang no breeding place suitable for these mosquitoes. It is still impossible to say exactly what mosquitoes were carrying malaria in 1901, but I think Myzorhynchus umbrosus was probably the most important one. Only two miles from the centre of Klang there is now, 1909, a spot in which this mosquito abounds, and in which 50 to 100% of the children suffer from enlargement of the spleen; the percentages varying universally with the distance they actually live from the mosquito’s breeding place.

In the earth drains and such wells as remain, there has been a great reduction in the number of larvae. The number of adults which can be caught varies very greatly. In the month of August 1909, during a period when the weather was dry, not an adult could be caught, although the most careful search was made. Yet two months later specimens of the above-mentioned species, particularly of Myzorhynchus separatus, were caught with great facility, and in fact for about a week rarely a night passed without my being attacked as I sat reading.

| 2.6 |

Proposals made to Government for drainage scheme |

Having made definite observations, which convinced me of the necessity of striking at the disease, I laid the facts before the Klang Sanitary Board in May 1901, with proposals for a drainage scheme. The proposals were accepted by the Board and were included in the proposed estimates submitted to the Government by the Board for 1902. This was entirely due to the strong support given to them by the Chairman, Mr. H. B. Ellerton; and I wish to record my grateful thanks to him not only for his support, but for many valuable suggestions in connection with the proposals. When it is borne in mind that I personally had no experience of either the tropics or of the methods of presenting proposals to the Government, those who have had experience of both will realise how much Klang owes to Mr. Ellerton.

The support of the State Surgeon of Selangor, Dr. E. A. O. Travers, was then sought; and in July 1901, I forwarded a report to him asking for support for the Board’s proposal. In it I pointed out that:

- (a)while the total number of cases treated at the hospital during the first half of 1901 showed an increase of 3.25% over the corresponding period of 1900, the increase in the number of malaria cases amounted to no less than 69%;

- (b)of these malaria cases 55% came from the town, while the estates, which were better drained, sent in only 11%;

- (c)to my personal knowledge, 60 houses out of 293 within the town boundary had been infected within the previous three and a half months;

- (d)the prevailing type of parasite was the tropical or malignant form;

- (e)a water supply was shortly to be introduced, and it would be unwise to bring increased moisture into a town already suffering from malaria without previously providing proper drainage; and

- (f)since in the returns from 1896 onwards malaria has been more prevalent in the latter part of the year, the marked increase of fever in the first six months of 1901 is a matter for serious consideration, and some action in the way of drainage is clearly indicated.

This report was accompanied by a plan of the town showing the general distribution of the swamps, the breeding places of Anopheles, and the houses infected by malaria. The proposals received from Dr. Travers the strongest support, and the Government not only indicated that the proposal would be favourably considered, but ultimately doubled the sum asked for by the Board.

| 2.7 |

The outbreak of 1901 |

It was soon evident that the end of the year was to make good our worst fears. The outbreak reached terrible proportions. The inhabitants of house after house went down before the disease in the months of September, October, November, and December, which period, incidentally I may mention, coincided with a marked rise in the level of the ground water of the town. It is difficult to convey any proper conception of such an outbreak and the misery it involves; but the following extracts from my notebook will show how much Government officers and their families suffered.

In the clerks’ new quarters there were 11 cases with one death; clerks’ old quarters, 4 cases; clerk of works’ quarters, 7 cases; adjoining quarters, 2 cases; post office, 2 cases; railway quarters, 16 cases; rest house, 5 cases; inspector of police’s quarters, 6 cases; police constables, 21 cases; in the district officer’s quarters the servants were attacked; in the surveyor’s quarters all the Europeans were attacked, the family consisting of the husband, wife, and two children. In my household all my servants were attacked (three in number). My wife and I escaped, I believe because the servants were sent to hospital at once and were kept there until their blood was found to be free from parasites, and they were dosed with quinine on their return to work. In addition we used citronella oil lavishly on our persons and clothing in the evenings, and our mosquito curtains were thoroughly searched and cleared of anophelines each night.

In addition to those occupying Government quarters, many Government officers were attacked who did not live in Government quarters; and I think two clerks’ quarters and the dresser’s quarters at the hospital were the only ones to escape. I may mention these had been attacked in the earlier part of the year.

In the lower lying town, the condition was more terrible. Hardly a house escaped. In many cases I found five and six persons attacked, and the observations I then made have left an indelible impression on my mind. Night after night I was called to see the sick in houses and found men in all stages of the disease. Many and many a time it was only to find the patient in the last stage of collapse or in burning fever. The whole population was demoralised; and when in November the death rate rose to the rate of 300‰, the Chinese suspended business entirely for three days, and devoted their energies to elaborate processions and other religious rites calculated to drive away the evil spirit.

| 2.8 |

Work done in Klang |

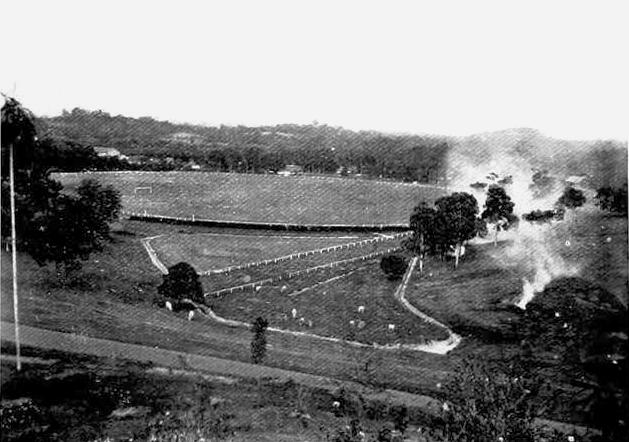

Although the money voted by Government did not become available until 1st January 1902, the Board was by no means idle in 1901. All the available Sanitary Board Staff was occupied in felling jungle, and clearing undergrowth, and doing some minor draining. Owners of private land were, under one of the Board’s laws, compelled to drain and clear their land. The section reads as follows and had been in force since 1890, although its power had been little invoked in Klang:

When any private tank or low marshy ground or any waste or stagnant water being within any private enclosure appears to the Board to be injurious to health or to be offensive to the neighbourhood, the Board shall by notice in writing require the owner of the said premises to cleanse or fill up such tank or marshy ground or to drain off or remove such marshy water.

This section2 gave the fullest powers to the Board, and it was freely used.

| 2.9 |

Cost |

During 1902 the sums listed in Table 2.3 were expended by the Board on draining and filling. This work included the drainage of swamps just outside the old town limits, some 16 acres in extent. It was not, however, finished all at once, and even in 1904 some small swamps were still in existence.

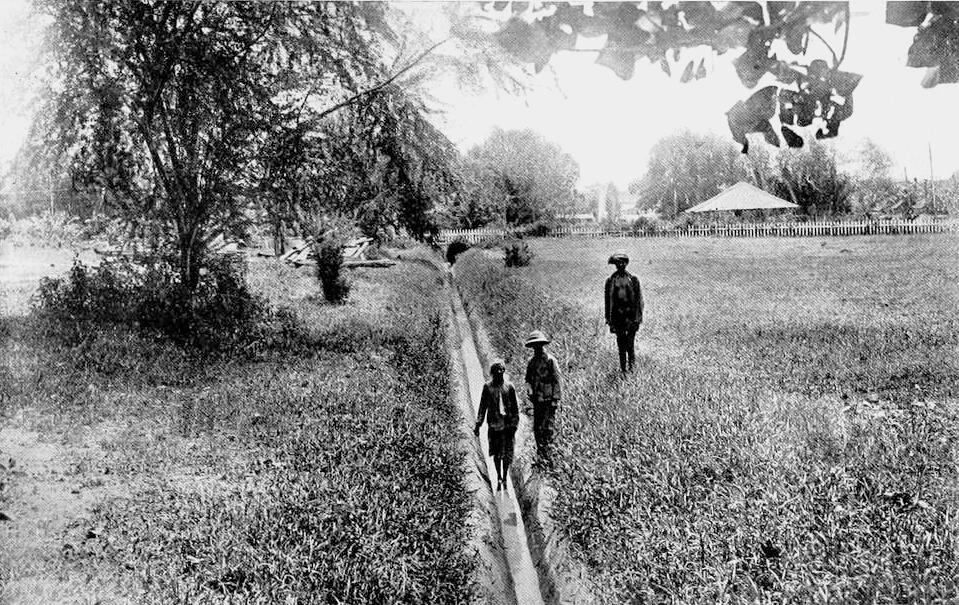

It was not until Mr. E. V. Carey pointed out that the only way of draining the swamps effectively was by contour drains at the foot of the hills, the method universally employed by planters, that these became really dry.

| Year | Item | Amount1 |

| 1901 | extension of brick drains | 750 |

| 1902 | extension of brick drains | 1,925 |

| filling in swamps | 8,579 | |

| main sewer | 3,856 | |

| 1903 | extension of existing drains | 368 |

| extension of brick drains | 2,340 | |

| filling in swamps | 1,303 | |

| main sewer | 6,142 | |

| 1904 | rebuilding another main sewer | 4,000 |

| extension of brick drains | 2,500 | |

| lowering of railway culverts | 1,500 | |

| 1905 | brick drains | 2,554 |

- 1

- Amounts in Straits dollars. The value of the dollar was fixed at two shillings and four pence of British money on 29thJanuary 1906. Before that it fluctuated with, and was of equal value to, the Mexican dollar.

I am indebted to Government for information regarding the actual expenditure. This expenditure may appear to be very great, but local circumstances are responsible for much of it.

| 2.10 |

Our Mistakes |

In the first place most of the houses of the town were situated close to the river, and connecting them with the river were several brick drains, or more correctly, open sewers. In order to drain the swamps of the town, which were further from the river than the houses, as will be seen from the plan (Figure 2.1), it was necessary to bring the water down these sewers. Unfortunately these sewers were at much too high a level to allow this; and consequently they had to be pulled up and rebuilt before the swamps could be effectively drained. In some places efforts were made to avoid this, but, in reviewing the result, I am convinced that had the original drains been entirely discarded, better results would have been obtained for the money spent. The drainage system of the town is bricked practically only where house sewage flows into it, and nine tenths of the system (as of 1909) is open earth drain. As will be seen from the sections relating to rural antimalarial sanitation, an open earth drainage system is sufficient in land such as Klang. Brick drains—the most expensive part of the works—were, as far as a malaria was concerned, unnecessary, and they should therefore properly be debited to ordinary sanitation.

Much money was spent on filling which could have been avoided had the town not been burdened by the legacy of its old brick drains.3 In some places where no fall could be obtained because a brick drain was too high, the land was raised by filling. This was very expensive work, and work to which I should be strongly opposed now. Until Mr. Carey pointed out the mistake, much money had been spent on filling in at the foot of the hills where our drains had proved ineffective.

I speak plainly of our mistakes, in order that others may benefit and avoid similar errors and extravagances. But for the necessity of constructing part of the system as a sewage system, and but for this unnecessary and expensive filling, there is no reason why the works at Klang should have cost more than the cost of draining the land, i.e., about £2 an acre; or in other words, about £100 instead of £3000. Thousands of acres have been cleared of malaria in the neighbourhood at this cost; and I can see no reason why Klang should not have been similarly dealt with at a similar cost.

| 2.11 |

Results |

These can be more conveniently dealt with when we come to consider the results of the works at Port Swettenham.