| 20 |

The Inland Hills |

| 20.1 |

The need for research |

The more I thought of the observations recorded in the last chapter, the more necessary it seemed there should be a thorough exploration of the habits and breeding places of the anophelines; for it was likely that out of such research important methods of controlling mosquitoes and malaria would be evolved. The subject was fascinating; and in a public lecture, given in Kuala Lumpur in 1910, I outlined my hopes:

But when we came to work out the anophelines, it was found that different species were found in the middle of the swamp from those on the hills. Nature has, therefore, carried out a great experiment. There were three groups of anophelines: one on the hills, one in the rice fields close to the hills, and a third lot in Krian far from the hills. Now, why do these vary? Clearly on account of something in the water, and it can easily be imagined that only a small change would bring the Bukit Gantang water to that of the Krian rice fields, and then malaria would disappear from Bukit Gantang, too. I believe that in this way a great anti-malaria method will be evolved, and I can look to the time when we will be able to play with species of anophelines, say to some “go,” and to others “come,” and abolish malaria with great ease, perhaps, at hardly any expense. Drainage schemes may become methods of the past, and future generations may smile to think of how their ancestors, who thought they were so clever, burned the house to cook the pig.

At all times I was eagerly looking for facts that would not fit in with my theories of malaria in hill and flat land; for exceptions either prove the rule, or throw new light on the whole subject. Above all, I sought a healthy town, village, or estate among the hills.

The last chapter concluded with this remark:

Finally, I would urge that our knowledge of the prevention of malaria would be materially advanced if more attention were paid to places where malaria does not exist. A truer idea of the part played by anophelines will thereby be obtained, and a less pessimistic view of the prevention of malaria will be taken than is often the case.

These two lines of thought dominated my researches in the following years. From 1909 onwards I was alert to discover some place among the hills from which malaria was absent, or even less in amount than would be expected; for the discovery of a healthy town or village among the hills would at once give a solution of the problem. Although I found, on several occasions, swampy valleys in the hills with comparatively little malaria, I could not discover any place completely free from the disease. The significance of what had happened in Kuala Lumpur in 1906 and 1907, and of the observations of Mr. Pratt, Dr. Fletcher, and Dr. Wellington—namely, that undisturbed jungle in the Inland Hills may be free of malaria; see Chapter 26—I had failed to realise.

| 20.2 |

The happy valley |

It was not, indeed, until Dr. C. Strickland had been some time engaged in his research, and visited parts of the Peninsula to which I had never been, that he found the long-sought-for “happy valley.”

In May 1912, Dr. Strickland arrived in the F.M.S. to take up malaria research, and more particularly to study the biology of Anopheles in relation to malaria. With pleasure, I showed him all that I thought could help him, and we discussed the lines of research indicated above. In a memorandum to Government I suggested the following as his course of study:

- healthy, flat land (coastal belt);

- healthy, wet land (Krian rice fields); and then

- working up from the coast into the valleys of Negri Sembilan, from what I believe healthy into what is unhealthy.

There is much to be learned here, I am sure, for the undrained swamps in valleys are certainly in many places healthier than those that are clean-weeded. Why this should be is clearly an important question? … The above seems to me the main line of research he should pursue.

More and more I had become convinced of the danger of opening ravines in hill land, and in 1913 wrote what represented my ideas at the moment:

There is no doubt that an ordinary jungle-covered ravine—harmful though it undoubtedly is—is less harmful than a well-drained swamp which breeds the mosquito N. willmori (A. maculatus). In the opening of an estate many changes occur in an undrained ravine, one of which—the filling of the ravine with silt from the clearings—is prejudicial to dangerous mosquitoes. Whereas the drainage of a ravine by open drainage is favourable to the more dangerous mosquitoes. I have no doubt that this is the explanation of many severe outbreaks of malaria which are reported as following the drainage of such ravines. In other words, it is the real explanation of what used to be explained by ‘turning up the soil.’ I do not pretend to know all about these swamps yet, but it is certainly best to leave them alone, neither to drain nor fell the jungle, until subsoil drainage is to be undertaken.

After my experience of the prevalence and danger of A. umbrosus in jungle, both in the Coastal Plain and Coastal Hills, it is not surprising, perhaps, that I was slow to conceive of the possibility of some jungle-covered ravines farther inland being free from A. umbrosus, and so free from malaria. Yet this was to prove the case; and although I had realised the advantage of leaving a ravine under jungle unless subsoil drained when opened, I had not observed the cause for it among the more Inland Hills.

It was not until 1915 that Dr. Strickland told me he had discovered not only a town in the hills which was free from malaria, but also the fact that A. umbrosus was not found in much of the hill land of the Peninsula; that it was confined largely to the Coastal Plains and Coastal Hills; and that in the jungle covered ravines of the Inland Hills it was represented only by an occasional umbrosus-like larva.

| 20.3 |

Observations in Kuala Lipis and the Pahang Railway construction |

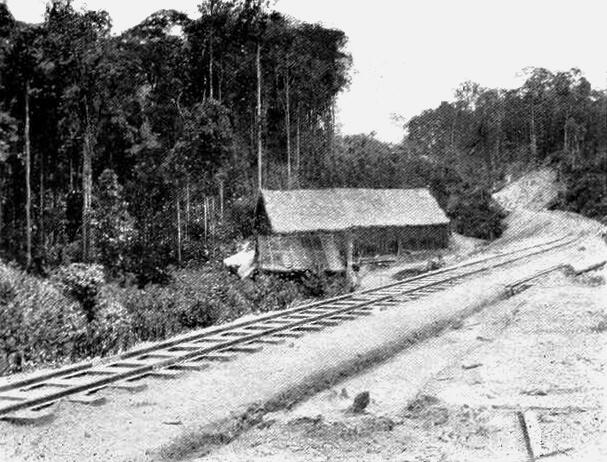

These discoveries were of the highest importance; and accompanied by Dr. Strickland I crossed the main range of hills to where a railway was being made through virgin jungle. From Tembeling to Kuala Lipis we searched the houses occupied by the construction coolies for adult mosquitoes, and examined numerous swamps and ravines for larvae. Where the sun was on the stream we often got A. maculatus; in the shade A. aitkeni; A. barbirostris, sinensis, kochii, and rossi were abundant; but never an A. umbrosus, either adult or larva.

We then visited the town of Kuala Lipis, which is situated on a promontory at the junction of two considerable rivers. Everywhere it was surrounded by virgin jungle; its ravines were still almost entirely covered by jungle.

On 7th August 1915, I made a house-to-house visit in the town; forty children were examined, and only two were found with enlarged spleen. One of the two had arrived in Kuala Lipis from Ulu Jelei only two days before; the other was two months from Raub—a notoriously malarial spot.

In the Malay school at Kuala Lipis, seven children out of seventeen had enlarged spleen; but enquiry showed only two of the children had been born in the town, the others having come from Raub (one year before), Kuala Medan (two years), Bentong (one year), Bandjar (four years), Pulau Tawa (two years). In the ravines of Kuala Lipis, only one umbrosus-like larva was found.

Since then, I have often discussed the health of Kuala Lipis with people who lived there before the railway came to it. They are unanimous not only in witnessing to its freedom from malaria, but to its freedom from all mosquitoes. So free was it from these pests that people usually slept without mosquito nets, which is not done by Europeans elsewhere in this country that I have heard of.

In travelling along the construction work of the railway, we had found the spleen rates were lower the more the place was closed in by virgin jungle, and the more permanent the class of people examined. For example, my notes record:

A summary of all living in Tembeling at the time shows that, out of ninety-seven, twenty-one had enlarged spleen; but of the most permanent part of the population, namely, those connected with the workshop and the children in the kongsis (workmens’ houses), most of whom had been two years and three months in Tembeling, only three out of thirty-six had enlarged spleens, a remarkably low rate when we consider that the cleared area of the town probably does not exceed ten acres, and that it is entirely surrounded by virgin jungle.

In contrast to this:

Tembeling Estate—We found that, among twenty-two Tamil adults on Tembeling Estate, eighteen had enlarged spleens, and of the eight Tamil children, all had enlarged spleens. … Krambit, like Tembeling, is shut in by virgin jungle, except that towards the west a portion of the land is covered by lalang, intersected by ravines, shaded by secondary growth.

At Krambit, we found six children, none of whom had an enlarged spleen.

| 20.4 |

Observations on the railway construction at Batu Arang in Selangor |

In view of the absence of A. umbrosus from the part of the State of Pahang which we had just visited, I considered it would be of interest to visit some railway construction then being undertaken in the Coastal Hills of Selangor, where I expected to find A. umbrosus. In this we were not disappointed, as the catches of adults reported in Table 20.1 show; only a few minutes were spent in each house.

| Date | Location | A. umbrosus (n) | Other Anopheles |

| 12/9/15 | Station master’s room | 12 | |

| Rest house | 2 | ||

| Chinese house | 7 | 1 (A. maculatus) | |

| Clerk’s house | 4 | ||

| 13/9/15 | Station master’s house | 26 | |

| Chinese coolie’s lines, 11/2 miles | 12 | ||

| 14/9/15 | 5th-mile lines (abandoned) | 2 | |

| Railway lines at Kundong | 18 | ||

| Wood-cutter’s house | 2 | 4 (A. barbirostris) | |

| Railway lines, 11/2 miles from Kuang | 1 | ||

| Total | 86 | 5 |

Everywhere, in swamps both open and under jungle, we found the larvae of A. umbrosus; and as this was hill land, the swamps were in the ravines. The larvae of A. aitkeni, A. barbirostris, and A. rossi were also taken.

| 20.5 |

Observations in the State of Pahang from the Gap to Ginting Simpah via Tras and Bentong |

In order to exclude the chance that A. umbrosus had been absent for some unknown reason during my previous visit to Pahang with Dr. Strickland, I again visited it by road. Most of the road is through virgin jungle; here and there dotted along it are P.W.D. coolie lines, a wood-cutter’s house, an occasional shop, and maybe a small native holding planted with rubber or fruit trees.

The larvae of A. aitkeni, maculatus, barbirostris, aconitus, and kochii were taken, each in its usual breeding place:

With the exception of the houses in Tras and Bentong, all the houses examined for adult Anopheles during this three days’ trip were situated in the midst of heavy virgin jungle; but nowhere was A. umbrosus taken, in remarkable contrast to my experience in Batu Arang, Batu Tiga, and the flat-land estates of Klang.

Such was Dr. Strickland’s important discovery. He had found a zone of land—the “Inland Hills”—which is not malarial when under virgin jungle, but becomes intensely malarial when the ravines are drained and cleared of jungle. This zone is a complete contrast to the “Coastal Plain,” which is malarial when under virgin jungle, and becomes non-malarial when the jungle is felled and the land drained. It differs, too, from the “Coastal Hills,” which are malarial, whether the land be under jungle or cleared. The differentiation of these hill zones was possible from the discovery of the peculiar distribution of the mosquito, A. umbrosus.

I have called it Dr. Strickland’s discovery, because to him more than to any other, our knowledge on this point is due! It is true, as will be found in Dr. Wellington’s interesting Chapter 26, on “The Malaria of Kuala Lumpur,” that the absence of anopheline larvae from ravines had been reported as early as 1907 by Mr. Pratt, and confirmed by Dr. Wellington in 1909. But this had failed to carry conviction; partly because the observations had not been published in detail; partly because they were in flat contradiction with what was known of apparently similar hill land; partly because no explanation of the contradiction was forthcoming; and mainly because no one then suspected the peculiar distribution of A. umbrosus.

It was reported that no anophelines were found in the jungle-covered ravine. This was incorrect. For a description of the species of mosquitoes that live in the ravines of the Inland Hills, see Chapter 25, “On Mosquitoes.” There is no doubt that Messrs. Pratt, Fletcher and Wellington had caught more than a glimpse of the truth; and had there been an earlier investigation of the subject it would have been of the highest advantage to the Malay Peninsula.