| 27 |

Anti-malarial work in Singapore |

By P. S. Hunter, M.A., M.B., D.P.H., Deputy Health Officer, Singapore.

Prior to 1911, only temporary measures such as oiling of swamps, filling of pools, and the clearing and training of streams and ditches had been carried out, and nothing very permanent had been attempted. In that year, however, in the pandemic of malaria, Singapore suffered fairly severely, and it was felt that something more radical must be done to combat the disease.

| 27.1 |

A survey of malaria in the city; the Telok Blangah area |

In his annual report for 1910, Dr. Middleton, the Health Officer, had suggested that a wise course would be to institute “a systematic examination of school children for signs of present and past malaria, ascertain the locality of their present or recent abodes, and make an inspection of these localities for conditions contributing to the disease.” This actually was done in 1911 by Dr. Middleton himself and Dr. Finlayson; and they found that the most malarious district in Singapore was the Telok Blangah area. In August 1911, in the two Malay Vernacular Schools of that district, Telok Blangah School and Kampong Jago School, 46% and 29.5% respectively of the children were found to have enlarged spleens.

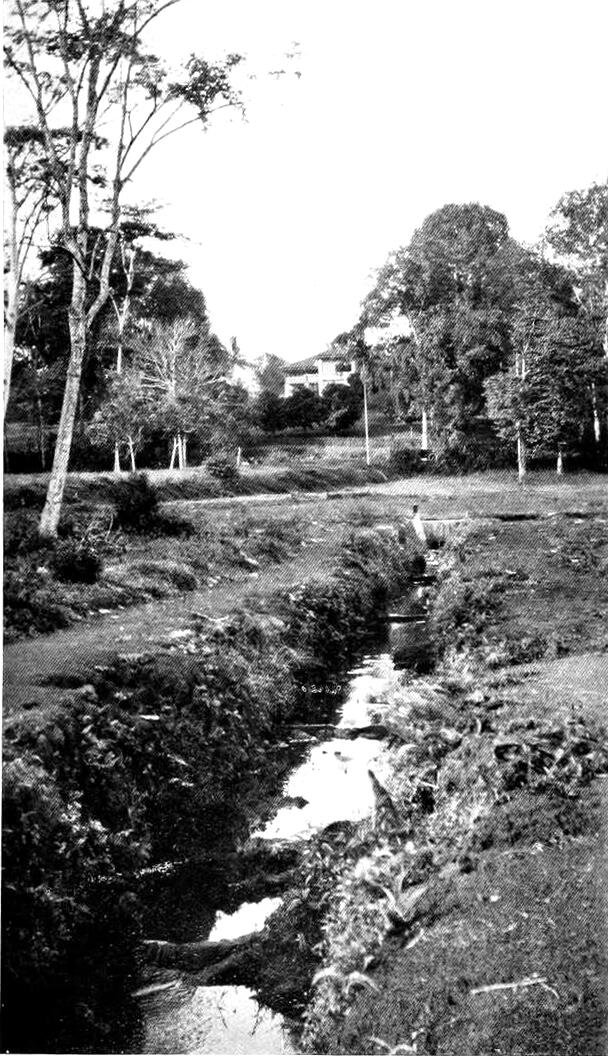

The district extends from the General Hospital to Morse Road and forms a strip of land a half to one mile wide along the harbour. Consisting as it did of large swampy low-lying areas at its eastern end, and hilly ground with its accompanying ravines and streams at its western end, it was felt that it was an extremely suitable area with which to experiment. It was known to be malarious and was not so large as to make supervision difficult. Accordingly, Dr. Malcolm Watson, whose anti-malarial measures had been so successful at Port Swettenham and Klang, was asked to advise as to the best method of dealing with the problem.

Dr. Watson first confirmed the findings of the spleen rates in the schools; and, further, to get more children and to determine more exactly the foci of malaria, made a house-to-house examination. In all, 571 children were examined, and 21% were found to have enlarged spleens. In the course of the examination, too, it was found that the hilly part of the district with its ravines and streams was much more malarious than the low-lying flat lands.

Thereafter, a detailed examination of the whole district was made to determine the varieties of anophelines breeding in the different localities. Depending on the conditions existing at each area, spleen rates, species of anophelines, and the variety of swamp or stream, Dr. Watson made his recommendations—filling, though he was not in favour of this generally; earth drains, hill-foot drains, brick drains, and subsoil pipes.

To the newly-formed Anti-malarial Committee the task of carrying out these recommendations was entrusted, and under the supervision of Dr. Finlayson, the work was immediately put in hand. During the period of construction, quinine was distributed free in the district, and an effort made toward the education of the people in the habits of mosquitoes by the exhibition of illustrative cards in the markets, schools, and public places generally.

| 27.2 |

The effects of drainage on the spleen rate |

The work was completed early in 1914. Whilst it was going on, and just after completion, Dr. Finlayson made several exhaustive house-to-house examinations of the children in the district. The figures are instructive. In April 1912, 508 were examined and 11.4% were found to have enlarged spleen. In April 1913, out of 485 examined, not quite 4% were similarly affected. The figures for the two schools during the period are shown in Table 27.1. A review of these figures shows that there was a progressive decrease of the spleen rate to practically zero.

| School | Date | No. examined | No. enlarged | Rate (%) |

| Telok Blangah | 1911 August | 39 | 18 | 46.1 |

| 1911 November | 37 | 18 | 48.6 | |

| 1912 April | 52 | 26 | 50.0 | |

| 1913 January | 58 | 12 | 20.7 | |

| 1913 May | 59 | 7 | 11.8 | |

| 1914 January | 54 | 7 | 13.0 | |

| 1914 September | 49 | 4 | 8.1 | |

| 1914 November | 54 | 2 | 3.7 | |

| Kampong Jago | 1911 August | 44 | 13 | 29.5 |

| 1912 April | 45 | 8 | 17.7 | |

| 1913 January | 57 | 8 | 15.7 | |

| 1913 May | 40 | 3 | 7.5 | |

| 1914 January | 49 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 1914 September | 46 | 3 | 6.5 |

During the war, the regular examination of these children could not be carried out as frequently as one would have wished; but I visited the schools at intervals and never found any indication that the spleen rates were rising. My last examination was a few days ago, when I found at Telok Blangah School two children with spleens just palpable, out of a total of fifty-two, and at Kampong Jago School, one child out of thirty-one.

All these figures speak for themselves, and I feel I cannot do better than to sum up in the words used by Dr. Watson in his second report of December 1914:

Three years ago it was decided to attempt to control malaria in the area of Telok Blangah by abolishing breeding places of the mosquitoes which carry the disease: the spleen rate was used as the test of the amount of malaria in the district, and by that test has been shown to have decreased to what for all practical purposes may be called zero. Similar measures carried out in other places have had similar results, and the Anti-malarial Committee of Singapore may, with confidence, look on the reduction of malaria in the Telok Blangah district, not as a mere accident, but as the direct result of the work done.

If there should have been any doubt as to the truth of these words in 1914, there can certainly be none now after the lapse of another five years.

The actual expenditure on the works was under $50,000, and a certain amount of that was spent on anti-malarial measures outside the area—a wonderfully small figure in consideration of the great results achieved.

From 1914 onwards, it has been part of my duties to keep watch on these areas and to look out for defects. The experience gained has been invaluable in enabling me to come to a decision as to the best method of dealing with anopheline breeding grounds in other parts of the municipal area.

Regarding the low-lying eastern part of the area, there is nothing much to say. It was originally swamp and was drained by open-earth drains. These open ditches are much the same as when first cut. They certainly dried up the ground, but they are too many and are a source of danger in themselves. But this point I shall refer to more fully later. Occasionally anophelines are found breeding in them, usually A. rossi, sometimes A. karwari, and rarely A. maculatus. By constant cleaning by the maintenance gangs and oiling where necessary, this breeding is kept down, but I am afraid that this part will never be successfully drained until the Singapore Harbour Board take steps to permanently lower the level of the subsoil water in their reclamation, through which the drainage of this whole area ultimately passes. It is purely an engineering problem. With some system of tidal valves it should not be impossible.

| 27.3 |

Anopheles maculatus in ravines |

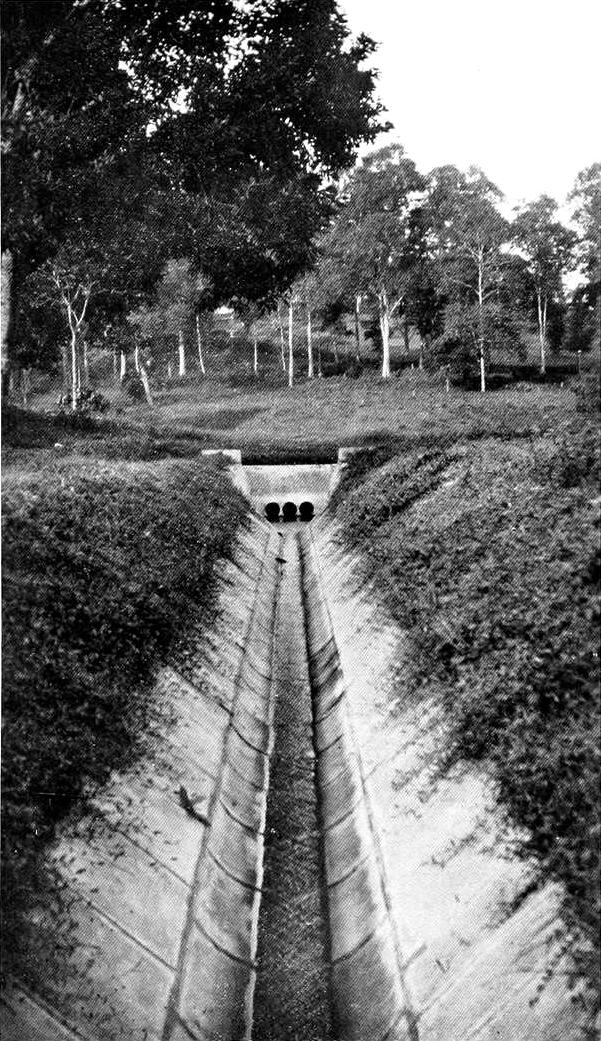

Turning to the hilly western end of the area, it is interesting to note that sooner or later, as Dr. Watson had forecasted, A. maculatus was found breeding in all the ravines—very often in the open-earth foot-hill drains that we ourselves had cut. The Radin Mas area is one of the best examples of this. It is a large, wide ravine about half a mile long, with a stream winding down the centre. Off the larger ravine open five smaller ones, each several hundred yards long. In the original scheme, it was recommended that the two top ravines only be piped, which was done. Then A. maculatus appeared in the spillways, necessitating the concreting of these spillways right down to the main stream. Later, all the other three ravines in which we had cut open drains began to show A. maculatus, so that these in turn have been subsoil-piped down to the main stream in the middle of the valley. On my last visit to this area in December 1919, I examined about twenty children in the Malay village there, and found none with enlarged spleen. The older inhabitants, too, assured me that there was no fewer now in the kampong.

I have followed the same policy over the whole of this area. Roughly, wherever A. maculatus has appeared, I have dealt with the breeding ground by subsoil piping. Open earth drains are all right at first, but they require constant supervision; and with the repeated cutting and cleaning that they are subjected to, they ultimately become too wide and deep, so that water stagnates in them.

And this brings me to a point which I wish to emphasise with regard to the habits of A. maculatus. In my experience, the dry weather is the time to be on one’s guard against this mosquito. In the very dry spell from August to October 1914, when we had practically no rain for three months, I found more A. maculatus breeding grounds both in the experimental district and in the municipal area generally than in the several years since. The reason is not far to seek. In wet weather, the larvae are being constantly flushed out from the smaller drains and never get a chance to develop. But I emphasise the point, because I found that, by cutting open drains, breeding grounds for A. maculatus had been created in many places. After a little dry weather, there is no water in the ditches except that coming from the springs, the outlets of which have been exposed by the cutting of the ditch itself—such a spring is an ideal breeding-ground for A. maculatus.

The danger of this is well illustrated in the following. A certain bungalow in the residential area stood on the high ground adjoining a large stretch of flat land. This low-lying flat land was originally a swamp, but had been drained by the cutting of several large, open ditches through it. At the time of which I speak, the weather had been very dry, and these open ditches, which usually stood half full, were empty and dry in their upper reaches. Two Europeans in the bungalow were suffering from malaria, while among the native servants and their children there were another six acute cases. The only anopheline breeding ground found was in one of these aforesaid dry ditches close to the house, where a small spring oozed from the side of the ditch, ran for a few feet, and finally disappeared in its floor. About half a dozen A. maculatus larvae were found in the whole spring. It was piped at the cost of a few dollars—and there were no further fresh cases of malaria.

| 27.4 |

Observations on various forms of drainage |

In the experimental area, I had much the same experience with two private reservoirs. Both these had been formed by the simple process of bunding across a ravine. The sides of the reservoirs were formed by the grassy banks, and the floor by the natural slope of the ravine. Under the scheme, the springs in the ravine-collecting area above each reservoir had been dealt with by pipes, the outlet of which delivered over a spill-way directly into the reservoir. All that was necessary was thought to have been done. But in a dry spell the water level of the reservoir fell, and a large expanse of sloping floor was exposed. In this exposed part were numerous springs, which showed themselves as trickles of water running down to the water level. My attention was first drawn to the danger by the occurrence of several cases of malaria in houses overlooking one of these reservoirs. I found A. maculatus breeding in these springs. A similar condition of affairs existed in the other reservoir. The fault was remedied by a little rough concreting and excavation of the floors.

From these and similar experiences, I concluded that the best way is to put down subsoil pipes wherever possible. The pipes in the area, some of which have been down for over six years, are still working perfectly, and there need never be any fear in employing this method of drainage. All that is necessary is to see that the pipes are of good strong material and that due allowance is made for storm-water, i.e., the pipes must be many times bigger than those capable of taking the ordinary dry weather flow.

Once pipes have been put down in a ravine, all that is necessary is that the maintenance gangs should visit the area at regular, short intervals to cut down the blukar and other secondary growth which soon springs up. If this is religiously done for eighteen months to two years, it is my experience to find that these coarser growths tend to die out, and are replaced by a firm, springy turf which no amount of storm-water will dislodge, and which requires a minimum of supervision and expenditure in upkeep.

| 27.5 |

Chinese squatters |

With regard to the maintenance of these anti-malarial areas after completion, there is one difficulty we have had in Singapore to which I feel I must make reference—and that is the trouble we have had to keep Chinese squatters from settling in the area—or to evict them once they have settled. Dr. Watson, in his 1914 Report, wrote very strongly on the subject. Just recently I found that one of the Radin Mas ravines had been converted into a huge vegetable garden. Wells had been dug over the pipes, and the area was slowly reverting into a worse condition than ever before. I say worse, advisedly, because the squatter, in addition to breeding mosquitoes, by keeping night-soil pits and using night-soil in his gardens, directly encourages the spread of diseases like typhoid, cholera, and dysentery. I feel that I cannot emphasise too strongly that no cultivation of any kind should be permitted in these areas.

Turning now to areas with which I am more familiar, because I have supervised them from the start, I have tried to put in practice the various lessons learned from the Telok Blangah area. During the past six years, new works have been constructed all over the town, but mostly in the residential districts. This residential area is essentially a hilly area, and roughly it is a system of small ravines, with the houses built on the sides. In the ravine was a swamp or a winding overgrown stream, with wet, muddy banks and springs oozing out at the foot-hills—all ideal breeding-grounds for A. maculatus, and sure enough A. maculatus was found sooner or later in all of them. To enable me to find the foci of malaria more quickly, I made arrangements with the medical practitioners to notify me whenever they attended a patient with a first attack of malaria. I found this very useful as, whenever I received notice of several cases in one locality, I visited the spot and found the anopheline breeding grounds long before I should have done in my routine search of the whole district.

| 27.6 |

Dangers of open drains |

Scattered over the municipality, there were several low-lying areas which had originally been swamps and which were drained by having open earth drains cut through them. And this brings me to a point to which I promised to refer later. My experience is that these swamps have had far too many ditches cut in them. These have certainly fulfilled their purpose in drying up the swamp. But as soon as the ground is freed from its water-logged condition, these ditches which become deeper and wider from the attentions of the maintenance gangs, stand half full of water, which is almost stagnant and breeds all sorts of mosquitoes. Further, as I have already pointed out, there is the danger that in a dry spell the level of the subsoil water falls, and springs are exposed in the ditches themselves. And in these springs A. maculatus breeds. And even without waiting for a dry spell, we may find we have created A. maculatus breeding grounds, as it frequently happens that with the drying up of a swamp the springs at the surrounding foot-hills are exposed. This was the condition of things in many flat areas in Singapore—and, as already pointed out, is the condition found in the eastern end of the Telok Blangah area itself. So far as possible with these areas, I have tried to eradicate the A. maculatus breeding grounds by subsoil piping all the springs at the foot-hills down to a main drain.

A swamp prior to being touched may, of anophelines, be breeding only A. sinensis; and, if by draining it, we are simply to create a suitable breeding ground for a more dangerous species, it had much better be left alone. So that it is obvious that, if we must drain, it must be very carefully done. Remembering these things, I undertook the drainage of a large swamp some 60 acres in extent lying behind Tanglin Barracks and extending from there to the Singapore River at Alexandra Road.

The natural drainage of the swamp was by way of the river. The swamp itself was knee-deep in water practically all over, and almost anywhere one could find A. sinensis larvae. The river was first cleared of silt in its lower part. In the process of clearing the river, about four dams, put in by Chinese squatters for the purpose of diverting water to their pig and duck ponds, were demolished. The course of the river, too, in its part adjoining the swamp, was cleared and straightened.

These simple measures in a month’s time did much to do away with the swamp. The removal of the dams lowered the river between two and three feet and permitted the water from the swamp to drain away. Large areas of it became quite dry as the level of the subsoil water fell.

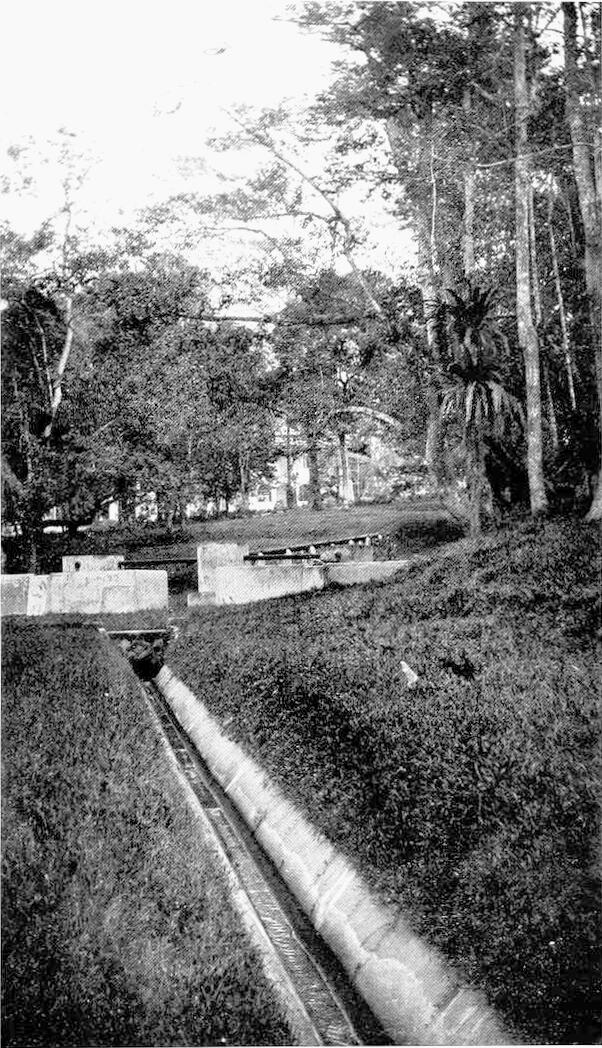

Thereafter one main drain was cut through the centre, with two smaller ones joining this and draining two ravines, which formed the head of the swamp. These, after a little time, were sufficient to completely dry the area until one can, today, walk over it in the wettest weather and find no water showing anywhere. But, and herein lies the danger, springs began to show at the foot-hills. As the area was well outside the residential part and there were no houses near, these springs were treated by being drained into the main drains by small open ditches. The big ditches I never find breed anophelines; but the small ones especially, if allowed to become grassed over, most certainly do. Now the ideal to aim at, in my opinion, is that all these springs should be subsoil piped to the nearest main drains. In this case, it would have been done but for lack of money. But already, with the demand for houses, construction is progressing on the sides of one of the ravines, and knowing the danger, I have advised that we immediately replace the main open drain in the ravine by a cement channel, and the small ditches tapping the springs by subsoil pipes discharging into this channel. And the work will be commenced at once and completed before the houses are occupied.

| 27.7 |

Concrete channels |

This brings me back to the method followed in the more purely residential areas with its system of narrow ravines. It is essentially the same as that for the swamp but more advanced. Originally I drained the marshy ground in the floor of a ravine by one open earth drain, or by clearing and straightening the existing stream. Then all springs were led by contour or foot-hill subsoil pipes to discharge over a concrete spillway into this. The main drain was left as an open ditch, and, practically without exception, I have never found them breeding when they are kept reasonably clear of obstructions, and pools are not allowed to form. But, with the rapid extension of the town, the more rigid insistence that houses should have a proper drainage scheme, and the care required to keep these open ditches from silting up, I have lately come to the conclusion that they must be replaced by a more permanent type of drains. One that our engineers have found very successful and not too expensive is a V-shaped open concrete channel with concrete slab revetments and turfed sides—the idea being that the ordinary dry weather flow is conveyed within the concrete area, flood water only reaching as far as the turf. After a time with reasonable supervision, these turfed sides become firm, and no amount of storm water will break them down. Into these drains the house drains will discharge. What is more important is that many people, despairing of ever seeing a proper water carriage sewage system installed, are putting in their own septic tanks and contact beds. The effluent from these in many cases must go by way of the ravines; and I, personally, have no objection to its being discharged into the main drains—provided the septic tanks are properly supervised and the main drain is concreted.

I made the experiment in one locality of combining the ordinary house drainage with the subsoil pipes. The house drains, which carry rain and bath water and kitchen washings only, were made to discharge over a sump. I would further advise that, when this is done, a grid should be interposed in the house drain to intercept refuse like egg-shells, etc.—which the cook insists on putting down the drain. Further, this grid should be placed well inside the compound where it will catch the householder’s eye. He certainly won’t look for it.

Though this experiment was quite successful, I don’t generally advise it. It is preferable to have house drains discharging into an open channel. I simply mention it because a case might easily arise where, to reach a main drain, the house drains might have to be prolonged for hundreds of yards, and a combination such as I have described would prove much less costly.

With regard to the flat lands in the municipal area with its many pig and duck ponds and the other varied collections of water, so dear to the heart of the Chinese vegetable gardener, nothing much has been done. Indeed, during the war nothing was allowed to be done. All that was possible was to keep a close watch on the larvae inhabitants of these ponds. Of anophelines only A. sinensis is ever found, though of course many other mosquitoes find a breeding place there.

| 27.8 |

Abundance of A. ludlowi in tidal areas |

Difficulty was experienced with three flat areas, all tidal, in that A. ludlowi periodically bred out in enormous numbers. Two of these were dealt with by filling, as they were simply a series of pools, into which the sea water reached at high tides. The third was in the Telok Blangah area in the reclamation adjoining Nelson Road.

Here all the open ditches occasionally bred A. ludlowi literally in millions. The only possible course was to deal with it by oiling, which is now regularly done. A point of interest in connection with this last is, that in his 1911 report Dr. Watson was at a loss to account for the fact that at Spottiswoode, the cleaner end of this area, there was so little malaria compared with what was found at Nelson Road, its fouler end. He suggested as a reason that some other anophelines might be breeding in the Nelson Road district. I have no doubt in my own mind that A. ludlowi was the culprit.

Just recently a new Anti-mosquito Ordinance has been passed by the Legislative Council, though it has not yet been out in operation. Under it, there are ample powers to deal effectively with all these low-lying areas.

Practically all these works described above have been done at municipal expense. I found very early that, if one had to wait for the owner of a property to carry out the drainage, one might wait for ever. And, apart from that, it is almost impossible to assess the cost for each owner or to estimate how much his property benefits. The following will illustrate what I mean.

In 1914, certain houses, under different ownership, built on high ground surrounding a ravine, were rendered untenable on account of malaria. In the floor of the ravine was a small cocoanut plantation. The water from the high ground showed as springs only in this plantation, and were all breeding A. maculatus. These were subsoil-piped in the usual way, with the result that malaria disappeared. Now it would obviously have been unfair to make the owner of the plantation pay. In any case, he was a poor man, and to pay would have meant bankruptcy. It was equally difficult to estimate the amount that each owner of the houses should pay, and there was no machinery for enforcing payment without endless litigation. Consequently the only thing to do was, what was done—to pipe the area at municipal expense. In my subsequent works this is pretty well the policy I always followed. But with the passing of the Anti-mosquito Ordinance and the likelihood, one hopes, of things being done on a much wider basis all over the island and money being spent on a lavish scale, it will be unfair any longer to put the whole burden on the taxpayer and the big property owners must be made to pay, at least in part.

Regarding the cost of these works it is not of much use my quoting figures. The prices of today bear no resemblance to those of a year ago, I had almost said yesterday; the upward rise in the price of materials being so rapid. But this I will say, that in carrying out anti-malarial—as against anti-mosquito works—I have often found that for a little judicious expenditure wonderful results may be obtained.

| 27.9 |

Anti-malarial work on the Island of Blakan Mati |

I should now like to describe my experience of what may be done in the way of controlling malaria in, say, a small self-contained district like a small island.

During the war I was mobilised with the local volunteers, and late in 1915 was sent as medical officer in charge on Blakan Mati. This island has a European population—mostly Garrison Artillery, of about 500. It is situated at the western entrance of the harbour, is about 3 miles long by a half to three quarters broad, and consists of high ground running its whole length with fairly steep slopes to the sea on either side. The northern side is fringed with mangrove, while the southern slope ends in cliff and sandy beach. The high ground on which the forts are situated is intersected with ravines which are full of tiny streams and innumerable springs.

I had known, prior to my going to live on the island, that malaria was rife amongst the troops; but until I saw my morning sick parade, I did not realise how bad it really was. And, if that were not enough, I was forcibly reminded that something must be done by finding several A. maculatus adults on my verandah in the first week of my occupation of the bungalow.

An anopheline survey of the whole island was immediately undertaken. About twenty anopheline breeding grounds were found. A. umbrosus and A. karwari were found in one or two places; in all the others our old friend A. maculatus.

Prior to 1915 very little in the way of permanent works had been done. A few pipes had been put down in places; but these were not acting as the undergrowth had been allowed to grow down into them. Mostly there were open earth drains with oil-drips. I may say that these drips, in a place like this at any rate, where the person responsible for their upkeep is continually being changed, are useless, and may even be dangerous from the false sense of security which they may give.

From my experience in Singapore, I determined that the only method to ensure success was to put down subsoil pipes; and this work was accordingly put in hand immediately. While the work was going on, temporary measures, as oil spraying regularly applied, were carried out.

Several difficulties were encountered in the course of the work. At one place just below the barracks, a series of springs were found below the level of high tide, but protected from the sea by a sand bar. The difficulty was overcome by the subsoil pipes being brought to discharge below high-tide level a system which was found to be quite satisfactory. Then again difficulty was experienced at a wet area artificially created by the raising of the natural subsoil level to supply water for the Dhoby ponds. In wet weather there was formed a large swamp several acres in extent, on the confines of which maculatus, karwari, and umbrosus were found breeding. As it was insisted that the Dhoby ponds must have an adequate supply of water, the drainage of this area was rendered rather difficult. The problem was cleverly solved, however, by the engineer who tapped two springs outcropping at a higher level some quarter of a mile away. These were led by an open concrete channel to the Dhoby ponds, and proved to give a sufficient supply. The swamp was then drained by very deeply-laid subsoil pipes, and the whole area became dry and remained so, even in the wettest weather.

On the very steep slopes of Serapong, the highest part of the island, we had trouble in the ravines with storm water. It came down so forcibly that it washed out the newly-made ground covering the pipes in the floor of the ravines. This was overcome by cutting a temporary channel in the side of the ravine, well clear of the subsoil pipes. After a time, when the floor of the ravines developed a strong firm turf, the storm water could do no harm.

Except for these and several minor difficulties, the work was easy. Roughly, the same principles were followed as in Singapore, except that on Blakan Mati the subsoil pipes were brought right down to the sea in most cases, instead of discharging into main open channels.

The drainage was completed in two years, that is, by the end of 1917. In a report of April 1917, by the engineer in charge of these works, I find that during 1916 a sum of £576 was spent, and that a further sum of £500, which, it was estimated, would easily complete the programme, was granted for 1917. It was further estimated that a sum of £200 would be required annually to keep the 60 acres occupied by these drains clear of vegetation. Personally, I think this sum rather high, as I feel certain that the coarse, thick vegetation will die out in two years, to be replaced by short turf, that will require a minimum of expenditure and supervision. Naturally, at the present day, these figures are valueless—and possibly they are not exact, in that a good deal of money seems to have been spent on the areas in previous years in clearing jungle, cutting open drains (and incidentally creating maculatus breeding grounds), oiling, etc., some of which money might have been required to be spent on the permanent works. But I only mention the figures because the engineer assured me on the completion of the work that the actual cost was only three times as much as was being spent in any one year on purely temporary measures.

In the following list of admissions for malaria, I have excluded those for Asiatic troops, as it would not be fair to include these. On the island there was always a detachment of the Johore military forces. They suffered a good deal from malaria, but as they were relieved every fortnight, their malaria was obviously contracted elsewhere. So, too, with the Indian gunners stationed on the island. It may be that during the war medical examination was less strict. At any rate, within a day of their arrival on the island, I have found recruits with enlarged spleens. Prior to 1914, the average number of European troops was in the neighbourhood of 350, and after that date about 260. During my stay on the island, many of the men belonged to B category and were suitable subjects for the depredations of the malarial parasite. The figures, so far as I could collect them from the hospital records available, are given in Table 27.2.

| Year | Admissions for malaria |

| 1912 | 163 |

| 1913 | 94 |

| 1914 | 48 |

| 1915 | 87 |

| 1916 | 23 |

| 1917 | 26 |

In 1916 and 1917 there were only sixteen and fourteen fresh cases respectively, the others being readmissions. I was unable to find the corresponding figures for previous years. On my return from home in 1919, I was assured that there had been no fresh cases of malaria in 1918, and to the best of my knowledge there were none in 1919.

At the risk of appearing tedious, I wish in conclusion to reiterate one or two points. It may be argued that the system of drainage I have advocated is expensive, as it certainly would be on, say, a rubber estate. But I do not pretend to advise for other than a thickly populated area such as Singapore. The anopheline we have to fear in Singapore is A. maculatus, and it is more likely to give trouble in dry weather than in wet. Whenever it appears, I believe the only sure way is to put its breeding place underground.

Dealing with a ravine, subsoil pipe the foot-hill springs into, if possible, one main open channel. This channel may be of the open-earth variety at first, if in a sparsely populated district; but as the town expands, it should be replaced by a drain of more permanent type.

In draining a swamp, don’t hurry. Try if anything can be done in the way of lowering the outlet, or clearing it of obstruction. Wait a little and then cut as few open ditches through it as possible. Having done so, and the ground having dried up, be on the lookout for springs at the foot-hills and surrounding ravines. Don’t wait for these to breed, but subsoil pipe them immediately into the nearest main ditch.

Where filling is absolutely necessary, consider always the advisability of first putting down subsoil pipes to take the drainage of the adjoining higher ground.

Having constructed anti-malarial drains, see that the areas are frequently visited and carefully tended for two years, and permit no cultivation of any kind. On this last point there should be no compromise.

| 27.10 |

Summary |

As regards results, I do not intend to quote any figures of the reduction of the death rates of malaria. I am afraid that, with our present antiquated system of death registration, whereby 50% of those who die are never seen in life by a medical man, but are certified (many of them as malaria) from an inspection of the body only, any figures one might quote would be valueless. But I personally feel sure, and I speak, too, for one of our leading practitioners, that in the town and its immediate surroundings there is now very little malaria contracted. And in any case the results obtained in Telok Blangah itself, and on Blakan Mati, are enough to convince me that we are working along the best lines to finally eradicate the disease.

There are, however, certain figures which give unequivocal evidence of the improved health of the town, namely the reduction in the total death rates. These show that, despite the influenza epidemic, there has been a saving of over 16,000 lives in the eight years (1912-1919). The remarkable reduction in the annual malaria curve shows that no small part of this saving of life must be attributed to the anti-malaria work. The subject is dealt with in more detail by Dr. Watson in Section 29.4, and will be better understood after a perusal of Chapter 28, which deals with statistics and the seasonal variations of malaria.