| 25 |

On mosquitoes |

| 25.1 |

Difficulty of classification |

One of the first difficulties confronting a medical officer who attempts mosquito control is the identification of the local mosquitoes, and even of the Anopheles. When, after Ross’s discovery that the mosquitoes carry malaria, the importance of the subject came to be recognised, Mr. Theobald, of the British Museum, undertook to receive, describe, and classify the insects sent to him; and he published a series of volumes in the course of the following six or seven years [37]. During the same period, a number of observers in different countries published descriptions of the mosquitoes taken by them [38–40]; with the result that few insects have escaped being described under one or more names.

As time went on and new specimens were discovered, the distinctive characters originally employed to separate various genera and species were often seen to be connected by intermediate forms, and shaded off into one another, making classification a matter of difficulty and controversy. It has been confusing in the extreme to the student; and, for the beginner, has proved an almost insuperable obstacle to progress.

Although considerable progress has now been made, and the synonymity of many species is worked out, it will yet probably be the simplest plan for a new worker to learn only the local species as species—without troubling too much about genera. It will be of the greatest advantage to him, also, if he can obtain some practical demonstrations of the insects from one familiar with the local species. This will save him many a weary hour, much wandering in the wilderness of the unknown, and may prevent him making serious mistakes.

| 25.2 |

Dr. Strickland’s researches |

It is not my purpose here to attempt to describe the distinctive features of our local Anopheles. The beginner will find the two keys—of larvae and of adult insects—prepared by Dr. C. Strickland helpful. After mastering these, he may proceed to the papers published by Drs. Strickland [41–52] and Stanton [53–55]. Dr. Barbour’s paper on the infecting of the local Anopheles must also be studied [56]; and the first of a new series of papers by Dr. Hacker on local malaria has been published [57].

Here I purpose merely to make some general observations on the different Anopheles and their relationship to malaria. In the course of this volume much has already been said on the subject; but there are some gaps which may with advantage be filled. In doing so, I propose to utilise some of Dr. C. Strickland’s unpublished observations. During the period of his work in the Malay Peninsula, he carefully recorded his observations in such a form that they admitted of tabulation. He did so in order that, as far as possible, the study of the conditions in which mosquitoes lived, or did not live, might be put on a mathematical basis; he aimed at giving something more than “impressions,” and hoped to supply a scientific basis for any conclusions he might draw, and any general statements he might make. His observations deal with 15,165 breeding places; and as a large number of details of each breeding place is recorded, and analysed, it will be realised how laborious the work was, and how valuable it is. General statements, such as that A. umbrosus is a pool breeder, or A. maculatus is a stream breeder, have been tested mathematically; and it is now possible to see how far they are true or untrue.

I understand Government does not propose to publish the report; but as Dr. Strickland has lent me a copy with permission to publish extracts, I gladly do so on account of the value of his observations, and of the important contributions he has made to our knowledge of mosquitoes, and the prevention of malaria in this country.

| 25.3 |

A. ludlowi |

So much has been said of it in Chapter 9 that I will content myself with emphasising the one great practical point. At first sight, the problem of its eradication seems insoluble. It is a prolific pool breeder; perhaps the most prolific Anopheles one meets. It breeds in almost every pool in the zone which it frequents; tufts of grass, bits of stick, and every sort of obstruction are usually found to shelter it in enormous numbers. Cracks in mud, hoof marks, blocked drains are loved by it.

The malaria it causes is shown by the high spleen rate; its zone has acquired a world-wide notoriety for unhealthiness; and it will be strange if there are not well-known local instances of its malignant power. The control of malaria in these circumstances may well daunt the bravest optimist. Yet I must insist that it can be controlled with ease by a simple system of clean, open drains; and this had been demonstrated time and again in the Malay Peninsula.

A. rossi (Giles) is comparatively rare, but does occur. It plays no part in the epidemiology of the disease in the F.M.S., as far as is known; just as it is a negligible factor in India. A. rossi var. indefinita is the common form here; it, too, is not, I believe, of practical importance.

| 25.4 |

The umbrosus group |

In the original description, A. umbrosus was given with only one white spot on the costal vein of the wing; but when I came to work with the insect, I found a second spot so common that I designated it A. umbrosus var. x. There are now known to be several Anopheles closely allied to it, although none are found in the profusion of A. umbrosus. A. umbrosus, as we saw, breeds in the inner Mangrove Zone, the Coastal Plain, the Coastal Hills; rarely, if ever, in the Inland Hills, although further research is required to map the line of its inland limit.

A. separatus is not unlike A. umbrosus, but has white bands on its palpi, which at once distinguishes it. It frequents the coastal region like A. umbrosus.

A. albotaeniatus also breeds in the inner mangrove, is very rarely taken in the Coastal Plain, but seems to become commoner in the Coastal Hills, although even here it is rare. The character chiefly distinguishing it from A. umbrosus is the broad, white banding of the hind legs. It is not known to be a natural carrier of malaria.

A. albotaeniatus var. montanus may be called the umbrosus of the Inland Hills; but in comparison with the number of A. umbrosus found in the Coastal Plains, it is a rare mosquito. It is like A. albotaeniatus, but has still more white on its legs. It is not known to be a natural carrier of malaria. Like A. umbrosus it is a jungle species, and Dr. Hacker’s observations would indicate that it disappears when the ravine is opened; indeed the whole umbrosus group just named are primarily jungle mosquitoes, living in pools, or very slowly streaming swamps.

| 25.5 |

The mosquitoes of virgin jungle |

In his chapter on “The Mosquitoes of Virgin Jungle,” Dr. C. Strickland, after describing the dense shade through which “not a sunbeam filters,” says:

As for mosquitoes of any sort they are very rare; all travellers in the virgin forest testify to it. Travellers will sleep there with impunity and not be bitten by mosquitoes.

But it is only in certain parts of the virgin forest, those parts which lie on the uplands and on the mountains. If the traveller enter the forest on the flat land, he will certainly be attacked by species of the umbrosus type, by Mansonia species, and Stegomyia scutellaris.

During the rainy season, the little pockets among the roots of the trees on the flat forest land become filled with small pools, if the land is not actually under flood from the neighbouring rivers. In such collections of water umbrosus will be found breeding. On the hills, of course, no such breeding grounds form.

During the dry season, the shallow valley beds, on the flat land and between the hills on the low hill-land, become morasses of sodden and wet ground between great gnarled trees and creeper roots. In these little pockets umbrosus delights to breed. As also aitkeni among the low hills, but not on the flat. … In this flat land virgin forest, I have never found any other species than umbrosus, and among the low hills none other than of that type or aitkeni.

In the uplands and mountains, aitkeni is the common species in the pools among the rocky streams and in the tributary ravines; occasionally specimens of the umbrosus type, but probably not umbrosus (Theobald), are found.

It may be recalled that in a paper entitled ‘Certain Observations in the Epidemiology of Malarial Fever in the Malay Peninsula,’ which was reported to Government, I said that umbrosus does not occur in the hill-land jungle. This is, I believe, true, sensu restricto, though some of the rare Anopheles mentioned in that paper as occurring in the hinterland hill jungle belong to that type.

As for other species, I have never found any in virgin forests. Still, I have found barbirostris, asiaticus, and leucosphyrus in situations in secondary jungle, which would seem to indicate that they too might be found in virgin forest. With regard to leucosphyrus, if it does occur in the virgin forest on the flat land, it must be very rare, and of no importance, because Watson, in all his records of flat-land estates, never mentions it. At Batu Arang, one day, Dr. Watson and I caught fifty umbrosus in a few minutes, but in two days did not see a leucosphyrus, although we were working along the edge of virgin jungle all the time.

In contrast to these jungle mosquitoes, I may just quote Dr. Strickland’s next paragraph:

Of the common Malay species, fuliginosus, albirostris, maculatus, karwari, sinensis, rossi, ludlowi and kochii, I have never found one in situations which cause one to suppose they would be found in virgin jungle. If ever they do it must be so rarely that it does not matter, except as a curiosity.

Writing of the peat belts, Dr. Strickland says:

I have only found one species of Anopheles in the peat deposits, namely, umbrosus, and that occurs in some quantity. I have examined peat swamps, and drained peat, and peat under jungle and peat opened up.

It will be remembered how a knowledge that A. maculatus did not live in peat reduced the amount of land drained by pipes on North Hummock Estate, and saved much money (see Section 16.1).

Again, in his paper on “The Mosquitoes of Stream Courses” (see Section 21.7 of this book), Dr. Strickland describes the different kinds of streams and rivers to be found, and says:

Small ravine stream under jungle. The stream is usually difficult to define; the whole is rather a streaming morass. I have recorded aitkeni, and species of the umbrosus group in such places.

In Table 21.3, Dr. Strickland gives the umbrosus group as only 47‰ of observed species on stream courses; but in the record of wells, umbrosus and sinensis head the list, both being 241‰.

These short extracts will have given some idea of A. umbrosus. Called by Mr. Theobald umbrosus from its dark colour, the name is no less appropriate if we look at its habits and haunts. As an adult it frequents the deep shades of the forest; and although, as a larva, it is often found in wells of pure water at a hill foot even in sunshine, it most frequently lives in stagnant pools of brown peaty water, or in the slowly streaming morasses of the virgin jungle.

It may, however, be found among grass and debris in a drain; but not if there is much current. So it is destroyed when a drain is cut through its breeding place; as we have seen in studying the opening up of the Coastal Plain. Fortunate it is that it should be so easily overcome, for with it disappears the malaria it carries; and, as Dr. Marshall Barbour says: “The evidence obtained in these experiments, both in regard to the artificially and naturally infected insects, would confirm Watson’s conclusion that A. umbrosus is an important carrier in Malaya.”

| 25.6 |

On the mosquitoes of ravines |

In the preceding pages on the umbrosus group, the reader will have learned that A. umbrosus is to be found not only in the “flat land” or Coastal Plain, but in the low hills or Coastal Hills, as I have called them in this volume, when these zones are undrained and under jungle. Further inland, in the “uplands and mountains,” or “Inland Hills,” A. umbrosus gives place to a closely allied species, A. albotaeniatus var. montanus.

In the ravines of both of the hill zones, that is, of the coastal and the Inland Hills, another mosquito is found. In almost every respect save two it is the antithesis of A. umbrosus. A. aitkeni, for that is its name, lives in mountain streams for preference; at the edges of the torrent, where it dashes down the granite mountain-side, the mosquito is found often in considerable quantity. Behind roots and rocks, in little bays of gravel or sand, it can be caught by one with some experience of methods appropriate to stream mosquitoes. Whether the speed of the current be great or little does not concern it much; it is found both in crystal streams on the steepest parts of our mountains, and in slowly running peaty swamps in the Coastal Hills.

But one condition it demands: there must be heavy shade, and, for preference, virgin jungle. The shade of a rubber estate is not sufficient. Yet shade is not the only condition; for it has never been found in the Coastal Plains even when under heavy forest. It is in the strictest sense the stream breeder of our hill land when under virgin forest; and not a pool breeder like A. umbrosus. Unlike A. umbrosus it rarely, if ever, attacks man; indeed, it rarely enters a house: nor is it like an Anopheles in its general appearance, being a little brownish-red, hunchbacked, culex-looking insect. A. umbrosus is a fierce biter, a strong flier, and lives well in captivity; A. aitkeni is the opposite. While A. umbrosus is an important carrier of malaria, A. aitkeni has never been infected experimentally; which can be said of few Anopheles, even of those known to be harmless under natural conditions.

In two respects it is akin to A. umbrosus: one is its presence in virgin jungle; the other its low place in the developmental scale of the Anopheles. A. umbrosus is covered mainly by hairs; it has not a ventral tuft of scales, like A. barbirostris and some others of the Myzorhynchus group. A. aitkeni has still less scale clothing, and has not even a patch of colour on its wings. Both belong to the group of primitive mosquitoes called by Major Christophers “the Proto-anopheles”; and it is not uninteresting that they support his theory of their ancient ancestry by being the sole and original inhabitants of our virgin jungle; for A. albotaeniatus var. montanus is perhaps an offshoot of the original umbrosus stock living in the coastal swamps, which has pushed its way up into the ravine swamps in the hills; at least so I often think of it.

It was the discovery that A. umbrosus did not extend beyond the Coastal Hills into the Inland Hills (where only the rarer umbrosus types were found) which led Dr. Strickland to his theory of the Inland Hills being non-malarious, as long as they were under jungle; a discovery which I discuss in Chapter 20.

| 25.6.1 |

When a ravine is opened |

Having described the mosquitoes of the ravines when under forest, it is now time to consider the changes that occur when the jungle is cut down : what happens to the original inhabitants; and what new-comers, if any, appear.

-

1.If the jungle be felled and burned off, and the

bottom of the ravine converted from a slowly streaming morass to a dry bed

intersected by clean-weeded drains carrying crystal streams sparkling in the

sunshine, the conditions are no longer suitable for the original inhabitants. A. umbrosus, montanus, and aitkeni all disappear: in their place appears the deadly A. maculatus, which, alone of all mosquitoes in Malaya, can

make its home in fast-running streams free from grass and other vegetation; and

which, as we saw, is the cause of the persistence of malaria in the hills (Chapter

10). This

mosquito is one of the most important carriers of malaria, an observation which has

been confirmed by Stanton, Strickland, and others; and so readily is it infected

artificially that Dr. Barbour used it as the “control” when

experimenting with other species.

Its liking for streams is shown statistically by Dr. Strickland’s tables. In streams there is, of course, often a deposit of silt; and among the species found in silts, A. maculatus occurs at the rate of 522‰ of the observations; the next, A. aconitus, which requires a grassy edge to the stream, being 175. In his table of the “Mosquitoes of Stream Courses” (Table 21.3), even although it includes streams of every description, from great rivers to streaming ravine morasses, many of which are unsuited to the insect, A. maculatus still heads the list with a rate of 340‰; while A. barbirostris comes next with 153. Commenting on this, Dr. Strickland says: “This table shows the very marked predominance of maculatus over the other species in this respect, and justifies the appellation usually given to it of a stream breeder, originated by Watson.”

Had the table been confined to fast-running streams in sunshine free from weeds, the position of A. maculatus would have been even more predominant; if indeed, as I believe, it would not have been the sole representative of these insects.

To the power it has of living in such streams is due the difficulty of eradicating the malaria of hill land by ordinary agricultural “cleanliness”; and the necessity there is for the use of oiling, subsoil drainage, or some other special measure.

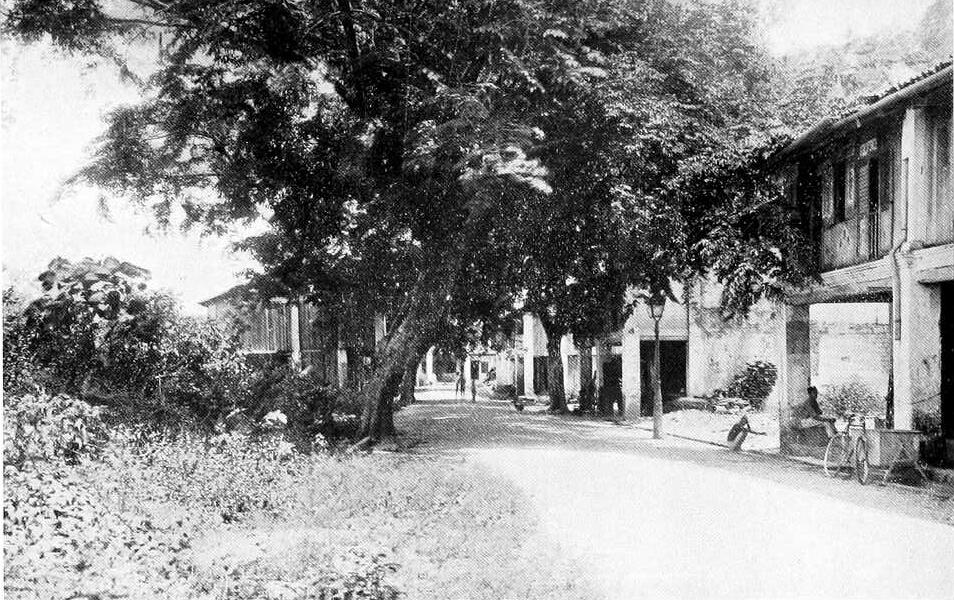

Figure 25.3: A drain that is almost obliterated. The ground is covered by ferns and secondary jungle. This “represents a stage in the reversion of the ravine to virgin jungle, when it is becoming unfit for A. maculatus, and has not yet become extensively suitable for A. umbrosus.”

Figure 25.3: A drain that is almost obliterated. The ground is covered by ferns and secondary jungle. This “represents a stage in the reversion of the ravine to virgin jungle, when it is becoming unfit for A. maculatus, and has not yet become extensively suitable for A. umbrosus.” Figure 25.4: A recently drained sendayang swamp. The sendayang is seen to be as high as a man, and forms a dense covering over the swamp. In the background is seen the edge of a secondary jungle which is creeping in ultimately to cover the Sendayang, so that once again “the jungle comes into its own."

Figure 25.4: A recently drained sendayang swamp. The sendayang is seen to be as high as a man, and forms a dense covering over the swamp. In the background is seen the edge of a secondary jungle which is creeping in ultimately to cover the Sendayang, so that once again “the jungle comes into its own." - 2.When the jungle in a ravine is felled, the timber is not always burned off; nor is the ravine always drained. The timber may be allowed to rot, and the ravine to remain a swamp. Then A. maculatus is no longer the sole and supreme occupant. In the portions of the ravine where the water is clearest and running freest, it will be found. In parts where the water is more stagnant, vegetable decomposition is going on under water, on the surface are frothy masses, and bubbles rise through the water as one wades in it; one takes A. sinensis, a mosquito much less fastidious than A. maculatus. At other spots, where there is little current, may be found such mosquitoes as A. barbirostris, A. kochii; and if the ravine is flat and some grass has grown up, it may be A. aconitus and A. fuliginosus. A. rossi readily appears if there is any pollution from human or animal excrement.

- 3.Into such a ravine, silt may be washed down from the hills. If grass be present, the silt may kill it out, and the decomposition of the grass unfits the ravine for A. maculatus, but makes it suitable for A. sinensis. On the other hand, silt pouring into an unopened ravine may kill out the jungle and allow the ingress of A. maculatus. If it is desired to preserve the jungle in a ravine, then measures must be taken to prevent silt being washed down. The favourite method at present is the “silt pit” (see Figure 25.2); but the end can also be achieved in some places by growing a belt of grass above the ravine.

- 4.Another condition of great interest, which may occur in ravines, is that where the ravine is drained, but weeds, and particularly ferns, have almost completely covered the ground. In addition to the close shade of the ferns, there is the shade of rubber or secondary jungle. This is a different condition from that of the original ravine when under virgin jungle, and is practically harmless from a malarial point of view. Owing to the drainage, there is no great area suitable for A. umbrosus to breed in; for the drains, even when obstructed in parts, are not comparable with the wide morass stretching from side to side of the ravine, when undrained and under jungle. Nor is it a favourite spot for A. maculatus, since the heavy shade of the ferns and trees is inimical to that insect. Some may be taken in the more open places, but nothing in comparison with the haul got were the ravine clean-weeded and without the shade of the ferns and weeds. This condition represents a stage in the reversion of the ravine to virgin jungle, when it is becoming unfit for A. maculatus, and has not yet become extensively suitable for A. umbrosus.

- 5.Yet another condition is sometimes found not favourable to the spread of malaria. The ravine is free from jungle, is swampy and undrained, and covered with “rushes,” known locally as “sendayang” (see Figure 25.4). This may form a complete cover to the water of the swamp; and where the shade is complete, no larvae will be taken as a rule; although occasionally A. sinensis will be found. Where, however, the shade is not complete, larvae may be found; the species depending on the quality of the water. As vegetable decomposition is the rule, the commonest species is A. sinensis; where the water is a little clearer, A. barbirostris, and where clearer still, A. maculatus. As the former two are not important carriers of malaria, the sendayang swamp is not specially dangerous; but one must beware of the open spaces. Where such a condition occurs on an estate and malaria exists, it is safer to drain the swamp and oil the drains, than trust to the cultivation of a complete cover of sendayang.

| 25.7 |

The silent war |

Such are a few of the kaleidoscopic views of malaria and mosquitoes presented in the different zones of this country, and even in one ravine in a single zone. Untouched by the hand of man, this is a country covered by an evergreen jungle, marked off into zones, some of which are malarial, and some non-malarial. When the jungle is rudely swept away, man seems to conquer. In reality a condition of “unstable equilibrium” has been produced; or rather it can be described more correctly as the beginning of a war that can only end in man’s defeat, however long it may be prolonged: man with knife and axe and fire; the jungle with its myriads of aerial troops.

Against the intruder, the jungle wages a ceaseless, though silent, warfare. It neither sleeps nor slumbers; and if it is to be kept in check, it requires of man endless effort. Ever vigilant, it sends forward, at every opportunity, its advance battalions. Along the drains creep the water-loving grasses and rushes; on their sides soon appear other grasses and tiny ferns. Grasses, ferns, wild bananas, and bushes grow on the dry ground of the ravines. Gradually leaves, sticks, and silt obliterate the drains; the ravine reverts to its original swamp; the ferns and bushes are replaced by the trees of the original forest. The jungle comes into its own. With all these changes, the insect life of the ravine changes too: at one period the insect inhabitant may carry disease; at another period it may be harmless. And one zone differs from another. It is in the power of man temporarily to arrest these changes at any stage favourable to himself, or to allow them to march to their destined end.

Interesting as these changes are from a scientific point of view, no less important are they to the sanitarian. From their study we have learned to understand why malaria appears, varies in intensity, or disappears; although at first sight there may be little to account for it all. And the knowledge has given us power already to advise what should be done, or left undone, to control the disease. As we learn more, perhaps the time will come when we shall be able to say to one species of Anopheles, “Come,” and to another, “Go,” and shall be able to “abolish malaria with great ease, perhaps at hardly any expense.”