| 14 |

Seafield estate: medical results |

| 14.1 |

Death rates |

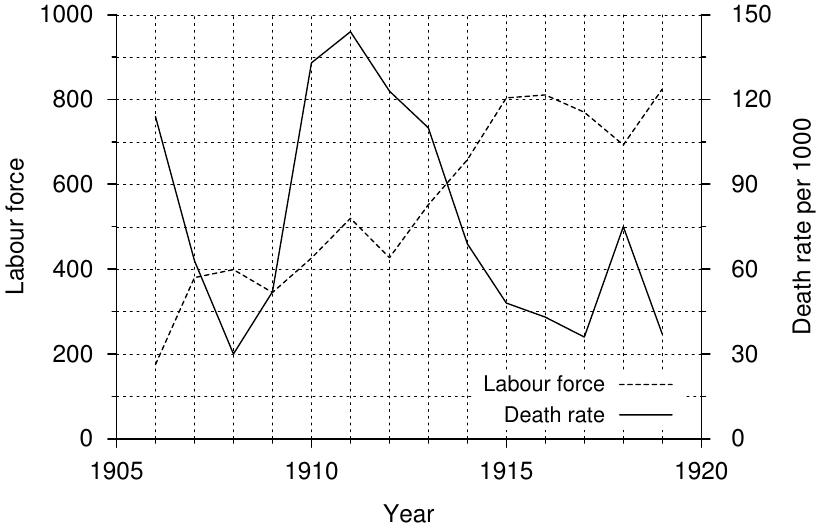

The drainage was begun in June 1911, and was completed at the end of 1915. The estate, of course, benefited from each acre of breeding place abolished, but the full benefit from the work was obviously not to be obtained for some time later. How much the health did improve will be seen from Table 14.1.

| Year | Average labour force | Death rate per 1000 |

| 1906 | 175 | 114 |

| 1907 | 380 | 63 |

| 1908 | 399 | 30 |

| 1909 | 345 | 52 |

| 1910 | 426 | 133 |

| 1911a | 520 | 144 |

| 1912 | 427 | 123 |

| 1913 | 552 | 110 |

| 1914 | 658 | 69 |

| 1915 | 804 | 48 |

| 1916 | 811 | 43 |

| 1917 | 770 | 36 |

| 1918b | 693 | 75 |

| 1919 | 825 | 37 |

- a

- Drainage begun

- b

- Influenza epidemic

| 14.2 |

Lives saved |

On 31st December 1919, there were no fewer than 998 workers, and 143 dependants, that is children and old people who do not work. Table 14.1 shows a fall in death rate, interrupted only by the influenza epidemic of 1918, and its continuation in 1919 (see Chapter 24). From it we can calculate roughly the number of lives saved in the last six years. Before doing so, however, I must point out that a labour force of over 600 coolies could not have been maintained unless the drainage had been carried out. On Seafield Estate, as on others in Malaya, labour is free, no indentured labour is allowed; no labourer can sign a contract. He comes of his own accord, usually on the recommendation of relatives living on the estate; he is free to leave on giving a month’s notice or paying a month’s wages. In practice he often leaves after pay day, without notice or payment in lieu of notice. When an estate has a reputation for being malarious, it has difficulty in obtaining labour. Were it possible to pour labour into such a place as Seafield was in 1911, so as to maintain an average labour force of 600 coolies, the death rate would be little short of 300‰ per annum (see Chapter 11).

In the year 1908 there were in the F.M.S. twenty-one estates (eighteen of them in hill land) with death rates over 200‰. An adjoining estate, and one not usually regarded as so malarious as Seafield, had death rates between 1906 and 1910 as follows: 146, 157, 176, 111, 152; and in 1908 the average death rate of the Batu Tiga District, in which Seafield is situated, was 140‰.

In our calculation of the number of lives saved, we may safely take 144, the death rate for 1911, as the base line; confident that it is an underestimate. As the figures in Table 14.2 show, this calculation indicates that labourers equivalent to over one half of the present labour force have been saved during the past six years.

| Year | No. of deaths at 144‰ | No. of actual deaths | No. of lives saved |

| 1914 | 94 | 48 | 46 |

| 1915 | 115 | 39 | 76 |

| 1916 | 116 | 35 | 81 |

| 1917 | 109 | 28 | 81 |

| 1918 | 99 | 52 | 47 |

| 1919 | 113 | 31 | 82 |

The reputation of the estate for health is now such that coolies come to it freely from India; indeed the year 1919 tested the health conditions severely; for no fewer than 957 new coolies arrived from India, most of them below the average in health, and large numbers suffering from influenza and its consequences. Not only had the rice famine affected them in India, but on the estate they were on short rice rations, supplemented by other foodstuffs, with the cooking of which they were unfamiliar. To this is attributable the increase of bowel diseases; for the digestive organs of the Tamil cannot be experimented on with impunity. Influenza, complicated with pneumonia, which apparently had existed since 1915, and reached its zenith in the epidemic of 1918, still haunts the immigrant ships. In the quarantine camp at Port Swettenham in 1919, no less than 5757 cases of influenza occurred; and there were 839 cases of pneumonia with 356 deaths.

Under these circumstances it is not surprising that in the last four months of the year influenza was epidemic in prevalence on the estate, although not in the severe form of 1918. There was also a slight increase in the incidence of malaria in the last few months of the year, causing three deaths; but for the first time in the history of the estate the great wave of malaria, which begins about April, did not occur on New Seafield. While it is evident malaria is still being propagated, it is satisfactory to note it is decreasing. We can, I think, look forward confidently to still further improvement, and to a death rate not exceeding 10‰; for if the death rate of uncontrolled malaria runs up to 300‰, there is abundant evidence that, where malaria is absent, the death rate of Indian labour forces in this country need not exceed 10‰.

| 14.3 |

Spleen rates and the children |

In the last paragraph of the first edition of this book, I commented on the relation between malaria and the labour problem, and said further: “No estate can ever have an assured labour force where the women wail, ‘We cannot have children here, and the children we bring with us die.’” Such is the cry on the unhealthy estates. It is in vain to contend with her “who weeps for her children and will not be comforted.”

Seafield was such a place a few years ago. Those who have not seen the barrenness of an intensely malarious estate will find it difficult to picture the conditions. In Chapter 11 Mr. Carey tells how in six years no Tamil child was born alive on New Amherst Estate. On 26th October 1909 I noted: “In three years five children have been born on New Seafield, of whom two have died; only three children born on Old Seafield, all died. Three children were conceived on the estate.” Pregnant women had come from India; malaria had usually caused miscarriage. But on the estate itself only three children had been conceived.

There is no complete record of all the children who died on the estate in the early years; it would have been sad reading. One of my earliest recollections is of a child being brought to me at Klang with greatly enlarged spleen. He rapidly improved on an ordinary mixture of quinine sulphate; and for months the parents sent to Klang for the medicine, although the identical mixture was made up on the estate. The boy was the only child of M—, the head kangany (or native overseer); he was given the quinine for years, in fact until he left for India in 1911. The story ends in tragedy. All through the malarious years, from 1905 to 1911, M—, his wife, and the child kept alive. These had no other children; but in 1911 the woman became pregnant; great anaemia followed; an attack of malaria brought on labour, perhaps a little premature. Twins were born. They and the mother died within twenty-four hours. It has always seemed to me a cruel fate that, after struggling through all the malarious years, she should have died just when we had begun the measures which were to control the disease. After his wife’s death, M— seemed to lose heart, and went to India, promising to return with more coolies. But he had seen his wife and so many of his friends and relatives buried on the estate that he did not return; and there was reason to suppose he stopped coolies from coming over. If he did, who shall blame him? I believe the boy lived.

Today the story is very different; although the change came gradually. On 23rd January 1917 on Old Seafield there were fourteen children without enlarged spleen who had been over six months on the estate; on New Seafield there were nineteen. On 18th January 1918 there were eighty-three children, of whom twenty had been born on the estate; not one of the twenty had enlarged spleen. In 1917 thirteen children were born on the estate; in the two succeeding years the numbers were seventeen and twenty-five.

| Year | Old Seafield | New Seafield | ||

| No. examined | Spleen rates (%) | No. examined | Spleen rates (%) | |

| 1905 | 16 | 68 | ||

| 1906 | 17 | 88 | ||

| 1909 | 11 | 81 | 36 | 58 |

| 1914 | 20 | 50 | 39 | 76 |

| 1915 | 12 | 83 | 30 | 60 |

| 1916 | 34 | 85 | 37 | 73 |

| 1917 | 32 | 28 | 36 | 47 |

| 1918 | 52 | 7 | 31 | 41 |

| 1919 | 107 | 21 | 59 | 30 |

In 1918 I recorded that although the spleen rate of New Seafield was still high (see Table 14.3), in more than half of the children the enlarged spleen was so small that it was just palpable. Of course it takes some time for chronically enlarged spleens to disappear—often three and four years; so it was of interest to note the spleen gradually going. I added, “To me the most gratifying sight of my last inspection of the labour force was, not so much the large number of healthy coolies, as the number of mothers with the healthiest babies imaginable in their arms.”

In January 1920 on Old Seafield in 18 of the 23 children with enlarged spleen, the organ was just palpable, and one child was a healthy infant twenty days old; 48 children with normal spleens had been over six months on the estate. On New Seafield there were five spleens of considerable size; the others were just palpable. Of the 41 children with normal spleens, 24 had been over six months on the estate. From these figures it is evident malaria is still being contracted on the estate; but it is becoming less intense as it decreases in amount.

To sum up, what was probably as intensely a malarious place as exists on the face of the earth, one which for the Indian labourer was uninhabitable except at an unjustifiable cost of life, is now so free from malaria, although not completely free, that Indians come to it readily, a large and efficient Indian labour force lives on it, and a further reduction in malaria and a further improvement in health may be anticipated with confidence.