| 1 |

Introduction |

| 1.1 |

British Administration in the Federated Malay States |

Only a generation ago a small band of Britons was sent to Malaya. Utterly insignificant in number, backed by no armed force to give weight to their words, they had strict orders only to advise the native chiefs, and not to rule. Civil war raged in the land. To take one step from the beaten track was to be lost in a forest, which had held men in check from the beginning of time. They were expected to create order from jungle, and turn strife to peace.

A hopeless task it might appear; but they brought with them those qualities which have spread the power and influence of Britain throughout the world. In the work of these men will be found the highest examples of the tact, of the scrupulous dealing with the native rulers, and of the sound administration which have built up the British Empire; and the progress they made is almost too great to grasp. They found it a land deep in the gloom of an evergreen forest whose darkness covered even darker deeds; for man fought with man, and almost every man’s hand was against his fellow’s. During the course of a generation, thousands of acres were wrested from jungle; thousands of people now live in peace and plenty; a railway stretches from end to end of the lands; roads, second to none, bear motors of every kind; while chiefs, who had never entered each other’s country except with sword in hand, met in harmony in conference with the man whose genius had made Federation possible.

In Swettenham’s History of British Malaya will be found the record of this marvellous change; and, with scientific instinct, the author contrasts the condition of the Federated States under British control with that of the other Malay States which were still under Siam and their native rulers. These form a “control” to the British experiment. To the Federated Malay States, British administration has brought wealth and prosperity to a degree to which can be found no parallel.

And with wealth has come health. From hundreds of square miles malaria, which formerly exacted a heavy toll from Malay and foreigner alike, has been driven out. Day by day it is being pushed back. Strong as its position now is in the hills, that too is being undermined, and it is my object to record the victories of the past and indicate the line of attack for the future.

| 1.2 |

Position and Climate |

The following observations have been made in portions of the Malay Peninsula lying between the 2nd and 6th degrees of North Latitude. The Peninsula itself lies between the 100th and 107th degrees of East Longitude. The climate is, therefore, to be described as equatorial; that is, it is equable, hot, moist, and without extremes either of heat or cold. Than such a climate none could be conceived more suitable for the propagation of the mosquito, and both in number of species and number of individuals, the Culicidae are well represented.

The rainfall is large, and is, on the whole, fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. In those parts of the States where a difference is noticeable, the wettest period is from September to March. The rainfall is always considerably heavier in localities near hills than on flat land near the coast. The average rainfall in the hilly inland districts varies between 100 and 200 inches, while in the drier parts of the States it is usually recorded at from 70 to 100 inches per annum.

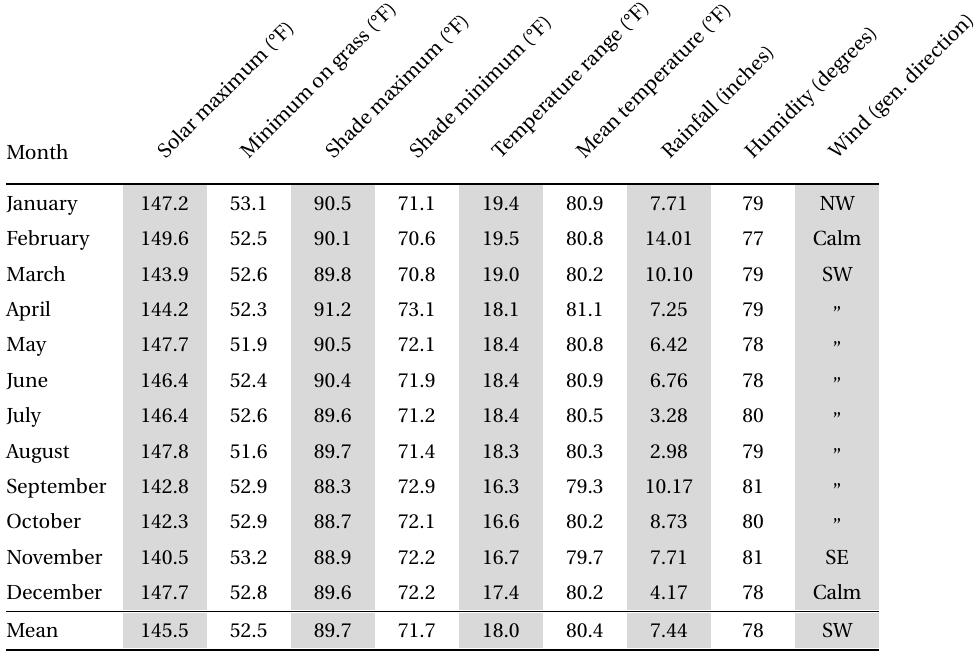

The general meteorological condition is as represented by the official return given in the medical report of Selangor for the year 1908 [1]. There are differences from year to year and between different places in the Peninsula, but these will be referred to later where necessary.

Under such conditions it is not surprising that malaria should, in certain places, be a veritable scourge; and it has been and is so. The former residence of the British Resident of the State of Perak, built on one of the finest sites in the capital, had to be abandoned on account of malaria; and when recently I visited it the fine drive up the hill was so overgrown that I was unable to force my way to the top.

Proposals for the abandonment of the town of Jugra at one time were made. Orders were actually given by telegraph by the High Commissioner to close Port Swettenham, within two months of its being opened, on account of the disease. A coffee estate was abandoned a few years ago on account of the impossibility of living on it, and at the present moment on many estates this disease is the cause of the gravest anxiety.

Since the disease is essentially a local one, it will be preferable if I first deal with my observations of various localities, and afterwards treat of their relationship with one another. Before doing so, however, it will be worthwhile glancing back for a moment at a brief history of our knowledge of malaria. We will then be better able to appreciate the position in 1900.

| 1.3 |

A short history of malaria [2] |

A disease which appears every day, every other day, or every fourth day, with a punctuality rivalling a railway schedule, and one, too, which goes through such definite phases as shivering, burning fever, sweating, and rapid recovery all within a few hours, is a phenomenon not readily to be overlooked. We find it referred to by both Greek and Latin writers. Though recognised when the attack was a regular quotidian, tertian, or quartan fever, it was not until cinchona came into use that the irregular forms of malaria were distinguished from other diseases accompanied by fever. Cinchona was brought to Europe about 1640 by the Countess D’El Cinchona, wife of the Viceroy of Peru, who had been cured of fever by the drug in that country. Its use soon spread through Europe and other continents with benefit to millions of unhappy beings.

By giving quinine the physician had a fairly certain test for a malarial fever. If the fever was checked by the drug it was malaria; if not, the fever was not malaria. This was a long step forward, yet it still gave no clue to the cause of the disease. Already its association with marshes had suggested a miasma, or an effluvium, or bad air, rising from the swamps, a theory which has given us two of the names for the disease, namely “paludism” and “malaria” (the mal aria, or bad air). Later, when the disease was found to be associated with disturbances of soil, quite apart from marshes, the theory of a telluric miasma was invented.

At an early date drainage was seen to drive out malaria from certain areas, and there were even suggestions that the mosquito might be the means of infection.

On 6th November 1880, A. Laveran, when working at Constantine in Algeria, discovered malaria parasites in human blood. The Italians, notably Golgi, Canalis, Marchiafava, Celli, and Bignami, soon took up this discovery and worked out the details of the three human malaria parasites. They showed how the quotidian, tertian, and quartan fevers were due to different and easily recognisable parasites; how the parasites multiplied in the blood by breaking up into spores; and how the fever paroxysm commences at the time when the spores are set free in the blood. Although by these discoveries we passed from the hypothesis that malaria is due to a miasma to the theory that it is due to a living organism, not unnaturally it was many years before the miasma hypothesis, which had held the field for centuries against all comers, was given up by the public.

The problem then was how these parasites passed from one human being to another; if they lived outside of man, where and in what condition? Failure attended every effort to discover the exit of the germs from the human body; the most exhaustive search for them in swamps and soil was fruitless. Manson, who had already traced a blood worm, the Filaria nocturna, into the mosquito, then suggested that certain forms of the malaria parasite, the motile filaments given off by the crescents, were for the purpose of infecting the mosquito; and that, when the infected mosquito died, the parasites escaped from its body into water, which when drunk by man infected him.

By a series of brilliant researches the genius of Ross dispelled the mystery. The parasites were taken up by certain mosquitoes (the Anopheles) when they sucked blood from a fever patient; male and female parasites were taken up; they conjugated to form a new parasite in the mosquito’s stomach wall; this sub-divided into many new fine threads or young parasites, which were injected into man when the mosquito took its next meal of blood. This wonderful development within the mosquito is completed in about ten days in a tropical climate.

Such a discovery, pregnant with so much good for humanity, at once attracted widespread attention in every country where malaria existed; unfortunately there are few countries from which it is absent. Commissions were despatched from European countries to the tropics; in a few months the discovery was confirmed in every detail. The years which have passed have still further confirmed the work completed by Ross between 21st August 1897 and August 1898.

Ross left India, in February 1899, to join the newly formed Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. A few months later he set out for West Africa to continue his studies, particularly the prevention of malaria and the habits of mosquitoes. The policy he adopted was that of mosquito reduction; arguing that by eliminating the mosquito, where this was practicable, and it seemed to be so in towns, the disease would soon be stamped out. Koch, who had gone to Java to study the problem, advocated the use of quinine, hoping to kill the parasites in man, thus preventing mosquitoes from becoming infected, and conveying the disease to a new host. The Italiansalso adopted this method on a large scale, combining with it, in many places, the screening of houses with wire-gauze in order to prevent mosquitoes from biting the inhabitants.

To bring the subject dramatically home to the public, Manson in 1900 carried out two experiments. A mosquito-proof house was built in a notoriously malarious spot in the Italian Campagna, and occupied by Drs. Sambon and Low throughout the most malarious months of the year. They worked in the fields during the day, but retired within the house before sunset. Neither observer contracted malaria. The other experiment was to bring Anopheles mosquitoes, which had fed on fever patients in Rome, to London, and there to make them bite two people, who had not previously suffered from malaria. Both men—one was Manson’s son—developed malaria, and parasites were demonstrated in their blood.

Such was the state of our knowledge when early in January 1901 I found myself in Klang, in the Federated Malay States.