| 28 |

On statistics |

Without statistics, no clear idea of the health of a community can be formed; to the sanitarian, they are as important as his accounts to the merchant. Before he can make out a case for the expenditure of money, he must show in statistical form the prevalence of the disease he desires to control. From a business point of view, statistics are necessary in order to determine if the results obtained are worth the money spent.

The next question that presents itself to the tropical worker is, What statistics should be compiled? To that there can only be one answer. Every figure that bears on the disease should be collected. At the time some figures may not appear of much value; but, if compiled and filed, they may prove of extraordinary value at a later period; such, for example, are routine spleen rates. Changes in health may be occurring of which the observer is not conscious at the moment; later he will realise them, and can then refer to the old spleen rates.

The statistical departments, which exist in most countries in Europe, are practically non-existent in many places in the tropics. To a large extent, the worker must compile and collate whatever statistics he requires. Generally speaking, he works in a narrow field; and this, apart from the personal equation, may lead to error and false conclusions. In this chapter, I wish to put the beginner on his guard against some fallacies; at the same time show how valuable figures may be when local conditions are known.

| 28.1 |

Hospital statistics |

Admissions for malaria, checked by the microscope, form series of facts of great value. Unfortunately they do not include all cases of malaria, as some may have had quinine shortly before admission, or for other reasons the parasites may not be found. This error may generally be considered as a constant and so be disregarded; and the figures are of great value.

Out-patients treated for malaria are less likely to have their blood examined, and the records are less exact. Both out-patients and in-patients may reappear time and again for treatment, and it is usually impossible to say if the patients are suffering from new infections or relapses.

Nevertheless, the number of admissions and the number of out-patients run an almost parallel course in the ordinary native hospital, and the gross figures of each, even admitting they contain many errors in diagnosis, throw much light on the health of a place, and should not be discarded.

When there is much malaria on an estate, some cases are admitted to hospital; but many are not. For where malaria is severe, and the cases are numerous, the hospital accommodation is generally insufficient; this is particularly so when a seasonal wave is severe, and 30 to 40% of the labour force is incapacitated. When, however, the malaria has been controlled and reduced in amount, it is possible to admit every case with an abnormal temperature. The admissions for malaria may, therefore, show no great fall, and the observer might be misled if he considers merely the admissions; the error can be detected by examining the number of out-patients. In the F.M.S. this frequently happens; no cases of malaria are treated as out-patients on some estates.

If some care be taken in ascertaining the exact residence of cases admitted to hospital, the observer can add considerably to the value of his figures. Having done this for some years, when in charge of the Government hospital at Klang, I can say that this correction is much less difficult than might be imagined; it demands, however, from the inquirer a fairly accurate knowledge of the local details of the countryside from which the patients come. When the exact residence is known, it is possible to make a “spot map” of the disease.

On large estates, conditions may vary widely on different divisions; there may be only half a mile between the best and the worst health, so the admissions and the daily number in hospital from each division should be recorded separately.

The great fallacy of admission rates for malaria as an indication of the health of a place is its variation with the number of non-immune new arrivals. Many new arrivals will raise the admission rate with great rapidity. This is seen when a batch of new coolies arrives on a malarial estate. If no others come, the admission rate gradually falls, until it is so low that the observer may imagine the place has become healthy; but it is not so. Other new arrivals will again send up the admission rate. A fall in the admission rate by itself cannot, therefore, be regarded as proof of the control of malaria. As I will show, the observer can guard himself from mistake by ascertaining the spleen rate.

The observer is liable to be misled by a fall in the admission rate (and as will be seen by the death rate), chiefly when the labour force is under 400. Above that number there is less chance of mistake; for, to maintain a labour force in the F.M.S. at a steady figure, something like 30 to 50% of the force must be recruited yearly; and this means there are sufficient new non-immune labourers to keep the disease in full flame. While referring to the admission rates for malaria, I would remind the reader that, when malaria is controlled, or when labour becomes immune and new arrivals stop coming in, not only do the admissions for malaria fall, but so do the admissions for all other diseases. Diarrhoea and dysentery are so frequently merely the terminal symptoms of chronic malaria, that the control of malaria has a notable effect on the admissions (and deaths) from these two diseases.

| 28.2 |

Deaths |

All towns tend to attract the sick and dying from the surrounding district; we saw it in the town of Klang in 1901; it occurs daily on a large scale in larger towns like Singapore, as Dr. Finlayson showed from a careful analysis of the malaria cases in hospital. While it is generally easy to make the required correction for residence when a patient is admitted to a hospital, it is more difficult to obtain correct information from those furnishing a death report.

What has been said of the admissions for malaria and other diseases applies largely to the deaths both from malaria and other diseases. Many new arrivals lead to a rise in the admission rates and death rates of malaria, of diarrhoea and dysentery, and generally of other diseases. Similarly, when the newcomers have become immune, the death rate drops, and may deceive the observer. The death rates, like the admission rates, must be read in the light of the spleen rates.

Sometimes I think of the two, the death rates and the spleen rates, as “cross bearings” which fix the health with greater accuracy than any other figures. In this book, I have used them more largely than any other figures, not because many other figures are not available, but because some selection must be made in a work of limited size; and these two sets of figures, in my opinion, give the most accurate information.

Apart from “rates” worked out on the population, the gross number of deaths varies with the seasonal prevalence of malaria, and presents a striking picture, to which I shall refer presently.

| 28.3 |

Spleen rates |

Of any single set of figures, the spleen rates appear to me to give, in practice, the most accurate idea of the amount of malaria in a place. The parasite rate makes so heavy a call on time, which in itself limits the number of observations the isolated tropical worker can make, that the spleen rate, based on a larger number of observations, is probably more accurate as a figure indicating the amount of malaria in a given population and locality.

It is usual to examine the children under ten years of age; but as few native children know their ages, the observer soon adopts a height and appearance standard which he almost unconsciously applies before beginning his examination. With a little practice, it is possible to examine the children almost as fast as they can walk past. My custom is to make the children pass from left to right; I use both hands; the left hand is placed below the ribs behind, and the right hand in front. The spleen, if enlarged, is then caught between the fingers of the two hands. This bimanual examination of the organ gives greater accuracy than an examination by one hand alone; for even quite small spleens can be pressed forward by the left hand fingers against the fingers of the right hand, which, with practice, become expert at detecting any abnormal resistance in the splenic region. Only rarely is it necessary to lay a child on his back, in order to relax the abdominal muscles. With adults it is almost essential to make the examination with the patient lying flat.

In making the examination in a country where a kala-azar does not exist, it must not be forgotten:

- That an enlarged spleen may persist for several years after a place has become non-malarial;

- that healthy children may have come quite recently to a malarial place and diluted the spleen rate;

- that children with enlarged spleen may come to a healthy place, the spleen rate of which is zero; and

- that healthy infants often have a palpable spleen.

In practice these corrections are easily made; and many instances have been given in previous chapters. Only a very unobservant observer will be misled. On one occasion I had separated the children with enlarged spleens from those with normal spleens, when I overheard a small boy among those with enlarged spleens say in Tamil, “We are the old ones—they are the new.” He was mightily pleased with his discovery, which was, as I found, correct.

In several places, I have shown how quickly new children acquire enlarged spleen in very malarial localities, even when they are receiving quinine; within two months, quite a high percentage may have enlargement of the organ. It will be found, too, that those who have not spleens are those most likely to have “fever” at the time of the examination. For example, there may be ten children who have been four months on the estate; seven will have enlarged spleen, and three will be suffering from “fever”; as a matter of fact, these are the figures of an observation.

Enlargement of the spleen indicates a certain degree of immunity to the “pyrexia” or “fever-producing toxin”; for, although these children are not suffering from “fever,” in a high percentage their blood contains parasites. Where the malaria, as indicated by the spleen rate, is only moderate in amount, say from 20 to 40%, it is mainly among the children with enlarged spleen that parasites are found.

It was a planter, Mr. Stevens of Pilmoor Estate, who first made me realise that enlarged spleen meant an approaching immunity. One day I was examining the children on his estate, and had picked out those with enlarged spleen, when he remarked that they were the children who were recovering from their malaria, and the others were still sick; some indeed had “fever” at the time I saw them. Having had this pointed out to me, observations on other estates soon confirmed it. Later on, I found it had been known for the last 300 years. The manner of my rediscovering it was as follows: When a medical student in 1894, I purchased a copy, in fair preservation, of Sydenham’s “Whole Works” (see Figure 28.1).

The book is, of course, of fascinating interest. At the time I made an index, in which I find “Giving of Peruvian Bark, the best method”; from which it would appear that 300 years ago there was a quinine controversy. There are also items “Dropsy at the end of Ague,” and “Hard belly in children.” But I had, however, forgotten all these things; nor were they recalled until, sometime after Mr. Stevens had made his remark on the spleens in children, I referred to the book, or at least to Chapter V. “Of the AGUES in the years 1661, ’62, ’63, ’64.”

Quinine, or rather Cinchona, Peruvian bark, or Jesuit’s powder, had come into use in Europe about 1640; and although widely used, there was still doubt about the best method and time to give it. Sydenham appears to have had no certain cure for malaria. Speaking of the Agues in the Fall he says:

But if there be any Man who knows how to stop the Career of these Agues, either by a Method or a Spefick, he is certainly obliged to discover a thing fo beneficial to Mankind; but if he refuse to do it, he is neither a good citizen, nor a prudent Man; for it does not become a good Citizen to reserve that for himself, which may be advantageous to Mankind; neither is it the part of a prudent Man to deprive himself of that Blessing he may reasonably expect from Heaven, if he makes it his business to promote the Good of the Publick; and truly, Virtue and Wisdom are more valu’d by good Men, than either Riches or Honour.

But tho it is hard to cure Agues in the Fall, yet I will mention what I have found most successful in the management of them.

He warns against purging and bleeding, but recommends sweating; then he goes on:

As to the Cure of Quartans, I suppose every who is but little conversant in this Art, knows how unsuccessful all the Methods have hitherto been, which are designed for the Cure of them, except the Peruvian Bark, which indeed oftener stops it than conquers it: for after it has ceased a Fortnight or three Weeks, to the great advantage of the Patient, who having been severely handled by it, has a little breathing time, it begins again afresh, tormenting him as bad as ever; and for the most part, how often soever the Medicine be repeated, it requires a long time before it can be vanquished: yet I will mention what I have observ’d concerning the Method of giving it.

But you must take care not to give the Jesuits Powder too soon, before the disease has a little wasted itself, unless the weakness of the Patient requires it should be given sooner: … I think it better to tincture the Blood leisurely with the aforesaid Medicine, and a good while before the Fit, than to endeavour at once to hinder the Fit just approaching, for by this means the Remedy has more time to perform its business thorowly, and then the Patient is freed from the danger that might happen by a sudden unseasonable Stop, whereby we endeavour to suppress the Fit that is now about to exert it-self with all its Might. Lastly, the Powder must be repeated at such short distances of Time, that the Virtue of the former Dose be not quite spent before the other be given: for by the frequent Repetition a good Habit of Body will be recover’d, and the disease wholly vanquish’d.

For the very young suffering from the spring and autumnal tertians, he says that bark may be used with good success, but he prefers to leave the whole business to Nature. He does not recommend either change of air or diet: “for I never found hitherto any ill from thence, if the Business be wholly left to Nature, which I often observ’d with admiration especially in Infants.” For the old he recommends a change of air to a warmer country, and cordials strengthening diet.

In all probability, malignant subtertian malaria did not exist in England and London in Sydenham’s time, so he was able to withhold the powders from infants, and it was possible for patients to go on with their fevers for months on end. This gave him the opportunity of observing the natural course of the disease in more favourable conditions, from certain points of view, than obtains in the tropics. Anyhow he did observe the disease closely, and we find the following on prognosis:

It is worth noting, That when those Autumnal Agues have a long time molested Children, there is no hope of recovery till the Region of the Belly, especially about the Spleen begins to be harden’d and to swell; for the Ague goes gradually off as this Symptom comes on; nor perhaps can you any other way better prognosticate the going off of the Disease in a short time, than by observing this Symptom, and the swelling of the Legs, which are sometimes seen in grown people.

That describes pretty accurately what Mr. Stevens discovered for himself and told me; which reminds me that I am writing a chapter “On Statistics,” and this is the section on Spleen Rates.

In malarial places where the spleen rate is 50% or over, the systematic use of quinine does not appear to affect the rate appreciably; but when malaria is less severe, or where the malarial season lasts only a few months, quinine does lower the spleen rate, as my old friend Major J. D. Graham, I.M.S., showed in 1914 [58].

| 28.4 |

The seasonal variation of malaria |

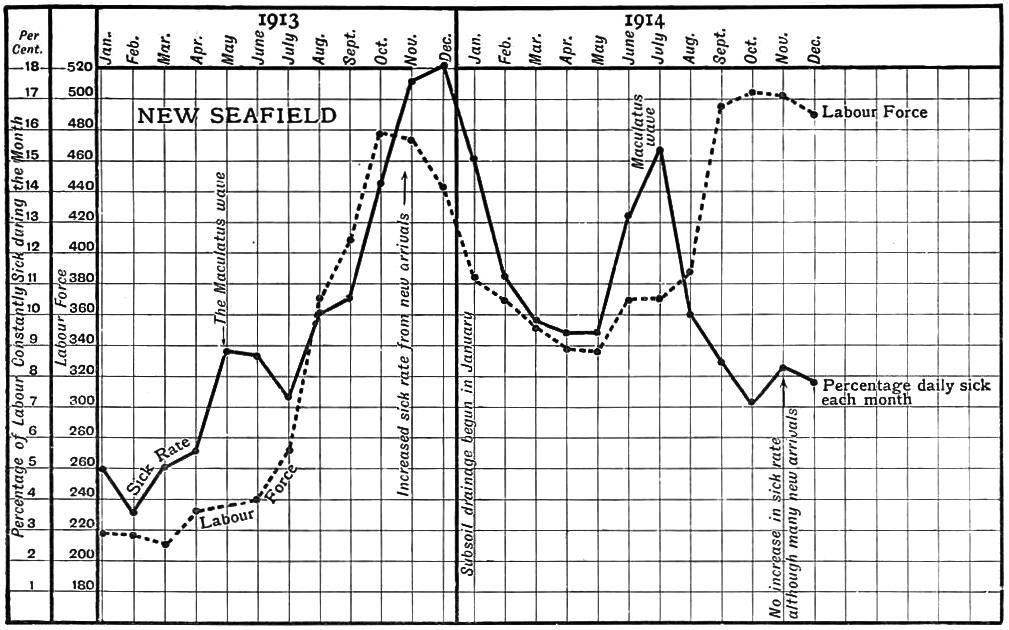

In Malaya, where the conditions are apparently so favourable to mosquitoes throughout the whole year, one would hardly expect any marked seasonal variation in the malaria. Yet it is not so. It is true that the introduction of many non-immune people into a malarious place, at any time of the year, will forthwith be followed by a severe outbreak of malaria, showing, as we know, that there is usually a considerable number of active insects present (Figure 28.2). But apart from such accidental outbursts, there are definite seasonal variations, which form curves or waves varying with the species carrying the disease. The subject has not been as fully worked out as it might have been, owing to the defective system of death registration in this country. We have, however, learned something.

When, at the end of 1901, the figures of malaria from the hospitals of the three coast districts of Selangor were charted, they showed notable differences. Whereas the malaria wave in Kuala Selangor district had reached its maximum in 1899, that in Klang still rose for two more years, and doubtlessly would have continued to rise but for the anti-malaria work done, for the population was rapidly increasing.

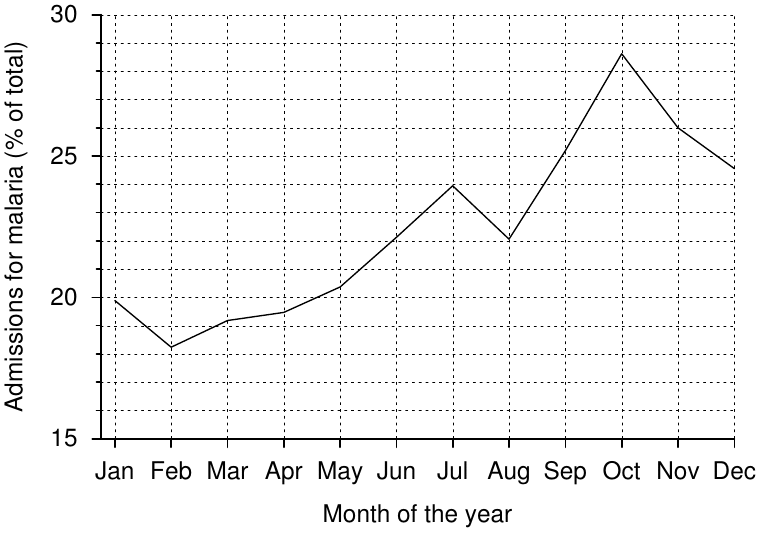

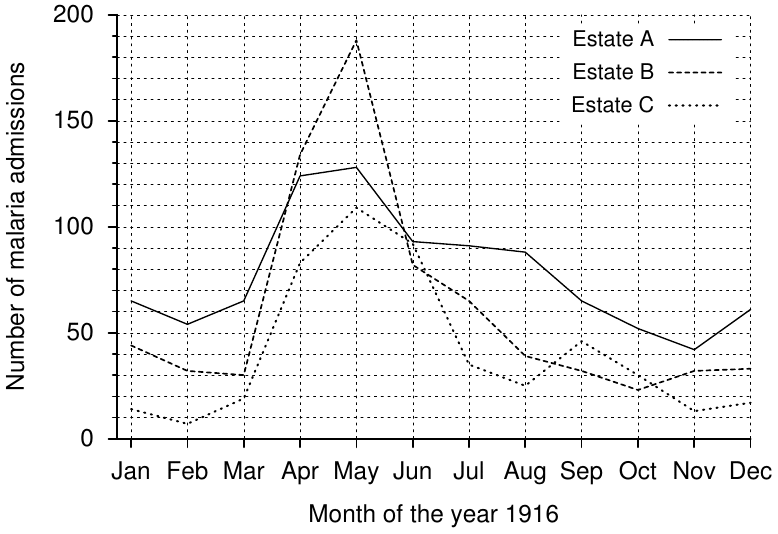

But there was another difference: this time between the Klang and Kuala Selangor charts on the one hand, and the Kuala Langat chart on the other. In the Klang chart, there was generally a steady increase of malaria throughout the year from the minimum in February to the maximum in October, with slight pause in August. Figure 28.3 represents the average of the percentages of malaria treated each month from 1893 to 1900. (The percentages [rather than the absolute case numbers] are averaged, so that the larger totals of the later years may not dominate the results unduly). The Kuala Langat chart, which in reality represented only the sickness of the inhabitants near to Jugra Hill, showed a sharp rise about April or May, when the maximum might be reached, and the epidemic as sharply subsiding in August, September, or October; which was quite a different figure from that of Klang District.

It was not until later that the significance of these differences came to be understood; and this is the explanation.

The curve with the maximum in November—the Klang chart (Figure 28.3)—is due to malaria caused by A. umbrosus, and possibly other pool breeders. It is unlikely that A. maculatus affected it in these years. The other curve with the wave in the centre months of the year—from April to September (Figure 28.4)—is the malaria of A. maculatus in hill land. The larvae of A. maculatus are greatly reduced in number by the heavy rains of November, December, and January; but in the two drier months, February and March, they appear in enormous numbers. Shortly afterwards the malaria wave appears. Figure 28.4 shows the monthly admissions for malaria of three hill land estates situated a few miles apart; the general similarity of the waves is striking; and I may add that the rise of the wave took place not merely in the month of April, but almost in the same week of the month, as Table 28.1 shows.

| Week ending | Estate A | Estate B | Estate C |

| 25th March | 13 | 10 | 5 |

| 1st April | 16 | 4 | 7 |

| 8th April | 21 | 12 | 6 |

| 15th April | 25 | 38 | 36 |

| 23rd April | 43 | 39 | 22 |

An attempt is now made to abort this wave by special attention to oiling between February and June, and particularly in the drier periods of these months. Good results appear to be obtained.

Where part of the area is flat and part hilly, the annual statistical curve is, of course, a combination of the two waves.