Poliomyelitis and polio vaccination: a critique of two vaccine-critical books

Michael Palmer, MD

1. Two books on the safety and efficacy of childhood vaccines that are worth reading

Readers may be familiar with these two books [1,2]. “Dissolving Illusions” has recently been updated and expanded, but this critique is based on the first edition from 2013.

Both books provide valuable information. I particularly appreciate “Dissolving Illusions” for its rich historic perspective, whereas “Turtles” thoroughly documents the astonishing lack, seemingly pertaining to all vaccines, of properly conducted studies to show their efficacy and safety. However, with both books, I found the treatment of poliomyelitis unconvincing, which prompted me to give this subject a closer look. This paper is the result.

2. What causes poliomyelitis?

2.1. Poliomyelitis according the textbooks

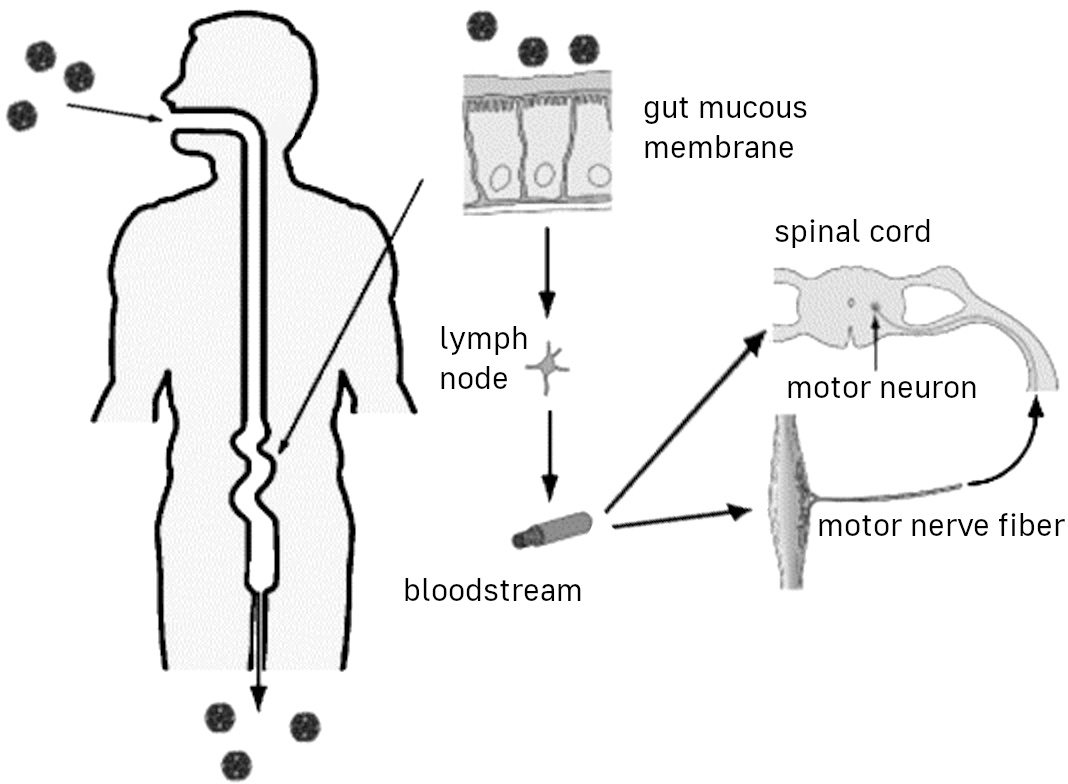

- Oral viral infection

- Multiplication in the gut mucosa, fecal excretion

- Spinal cord infection with paralytic disease in a small percentage of cases

According to the the mainstream view, polio is caused by a viral infection. There are three strains of poliovirus, all of which belong to the enterovirus family, like for example hepatitis A and Coxsackie viruses. One of the three strains is now considered extinct.

As with many other enteroviruses, the infection occurs through oral uptake, whereupon the virus multiplies in the gut. It is then excreted in the stool, and fecal contamination leads to oral uptake by the next person. Such fecal-oral transmission is a common pattern with many other enteric pathogens also.

In the the majority of infected persons, symptoms will be limited to mild, uncharacteristic and self-limiting enteric disease. Some others can have viral meningitis, manifest as headache, high fever and so on, but still no paralytic disease.

Only rarely will the CNS itself be affected, and in particular the motoneurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord and the brainstem. Destruction of these cells will disconnect the muscle cells under their control, and flaccid paralysis will be the result. Paralysis is observed only in about one in a thousand cases. Depending on the extent of the destruction, the paralysis can be transient or permanent, and in some cases deadly. It is not uncommon for paralytic patients to recover some but not all of their motor control.

2.2. Poliomyelitis according to “Turtles”

While both books are highly critical of the conventional polio narrative, “Turtles” is the more radical of the two, proposing that poliomyelitis has nothing to do with the poliovirus and is instead caused by DDT and possibly by other environmental poisons. To make its case, it emphasizes epidemiological “enigmas” such as the supposed association of poliomyelitis with modern western civilization. In its zeal to malign polio vaccination, it harps on the “Cutter incident”, which involved the occurrence of poliomyelitis in recipients of an early batch of the Salk vaccine, apparently unaware that this unfortunate event strongly corroborates the viral causation of the disease.

2.3. Poliomyelitis according to “Dissolving Illusions”

- Broadly similar to “Turtles” (but predates it)

- Does not dispute that poliovirus can cause poliomyelitis, yet still emphasizes the role of DDT and other factors:

Refined sugar, white flour, alcohol, tobacco, tonsillectomies, vaccines, antibiotics, DDT, and arsenic … Many thousands of people were needlessly paralyzed because the medical system refused to look at the consequences of these …

“Dissolving Illusions” is less radical, but this leaves the reader even more confused as to the question of disease causation. On the one hand, the book appears to accept that polioviruses can induce it, yet on the other it suggests that the sinfulness and debauchery of modern civilization are the true underlying causes—or maybe alternate ones; this distinction is not clearly addressed.

3. What evidence indicates that poliomyelitis is caused by viral infection?

- Infectious nature meticulously documented by Ivar Wickman (Swedish polio epidemic of 1905)—transmission mostly through people with abortive (non-paralytic) disease

- Experimental transmission of the infection from deceased child to two monkeys (Landsteiner and Popper, 1909)

- Experimental transmission via oral route to monkeys shown in numerous later studies

- Poliovirus can be isolated in the majority of clinically typical cases (and from the CNS of fatal cases)

- Efficacy of vaccination (particularly the live vaccine)

A transmissible nature of the disease had been suggested by earlier authors, but convincing evidence was compiled for the first time by the Swedish pediatrician Ivar Wickman [3]. His meticulous study of about 1000 cases of poliomyelitis that had occurred during the Swedish epidemic of 1905 showed convincingly that paralytic poliomyelitis was only the most severe form of the infection. Most cases were in fact “abortive”, i.e. clinically non-characteristic and indistinguishable from gastroenteritis or viral meningitis due to other causes. Nevertheless, even very mild cases could still transmit the infection to others, in whom paralytic disease might then become manifest.

Wickman’s diligence also shines through in his attempts to isolate a causative bacterium—unlike some contemporaries, he did not find one, and he concluded that an unknown virus must be the cause. This was soon confirmed by other investigators.

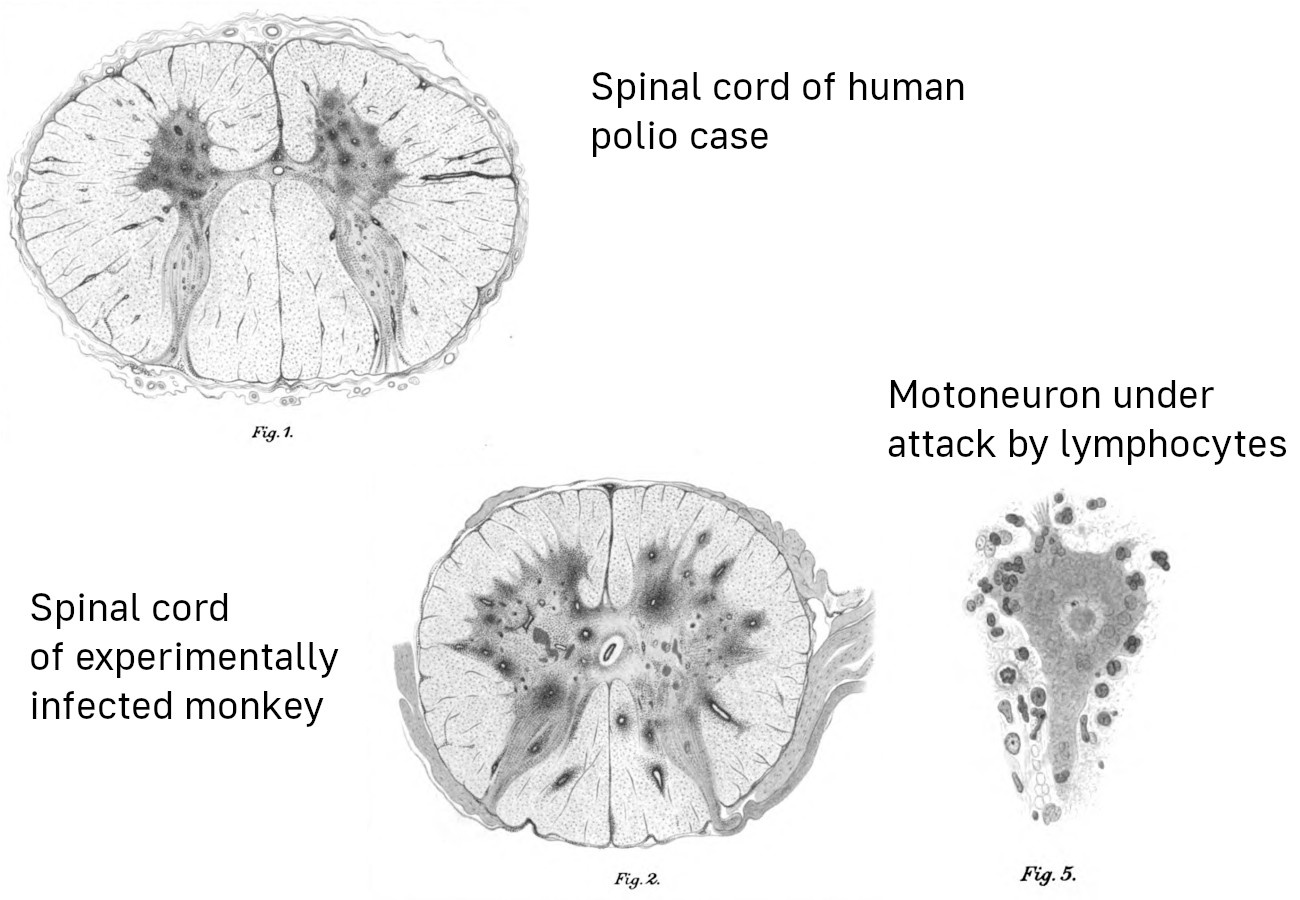

3.1. Landsteiner and Popper’s experiment

Wickman’s findings prompted the Viennese researchers Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper to attempt the experimental infection of monkeys, using CNS tissue samples from a boy who had succumbed to the disease. Both monkeys injected with these samples developed paralytic disease, and their CNS lesions closely resembled those from human victims. The attempt to infect further animals with tissue samples from the second monkey failed, most likely because the latter had been let live long enough to start producing neutralizing antibodies or even to extinguish the infection altogether. However, other researchers soon established serial passage in monkeys and subsequently other animals.

“Turtles” maintains that these early findings are invalid, because they relied on injection instead of on the natural oral route of infection. However, the book ignores numerous later studies that induced poliomyelitis in monkeys after oral infection; only some examples are cited here for illustration [4–7].

The drawings in this slide are taken from Landsteiner and Popper’s original study [8]. The dark splotches in the two spinal cord cross-sections are hemorrhagic foci of infection. The magnified view of a single large nerve cell surrounded by immune cells captures the pathogenetic mechanism of the disease: virus-infected motor nerve cells are destroyed by an immune attack, which results in the paralysis of the muscle fibers controlled by them.

At the time of these experiments, there were no methods for actually purifying and characterizing virus particles. Later technical advancements led to the isolation of three immunologically distinct poliovirus strains, all of which belonged to the enterovirus family. Both the Salk (inactivated) and the Sabin (live) vaccine contain derivatives of all three strains.

4. Efficacy of polio vaccination: the Russian experience

- The Soviet Union adopted the Sabin live vaccine in 1959

- Some 15 million persons received oral vaccine in 1959, and 77.5 million in 1960 (mainly between 2 months and 20 years old)

- For the sake of comparison, some administrative districts within the USSR received the inactivated (Salk) vaccine instead

Even though both the inactivated (“dead”) and the live polio vaccines were invented in America, the first country to test the live vaccine on a large scale was the USSR. The results, and the major logistics effort involved, are described in a study by Chumakov [9].

The paper acknowledges the support by Albert Sabin (the inventor of the live vaccine) and discusses the reason for going “all-in” at once: by vaccinating most of the susceptible population in one fell swoop, the risk would be minimized that the vaccine virus strains could spread serially from one susceptible person to the next, and in the process might acquire mutations that would restore their neurovirulence. It has since been found that this concern was well-founded; less thorough and comprehensive vaccination campaigns have indeed given rise to such mutations (see e.g. [10]).

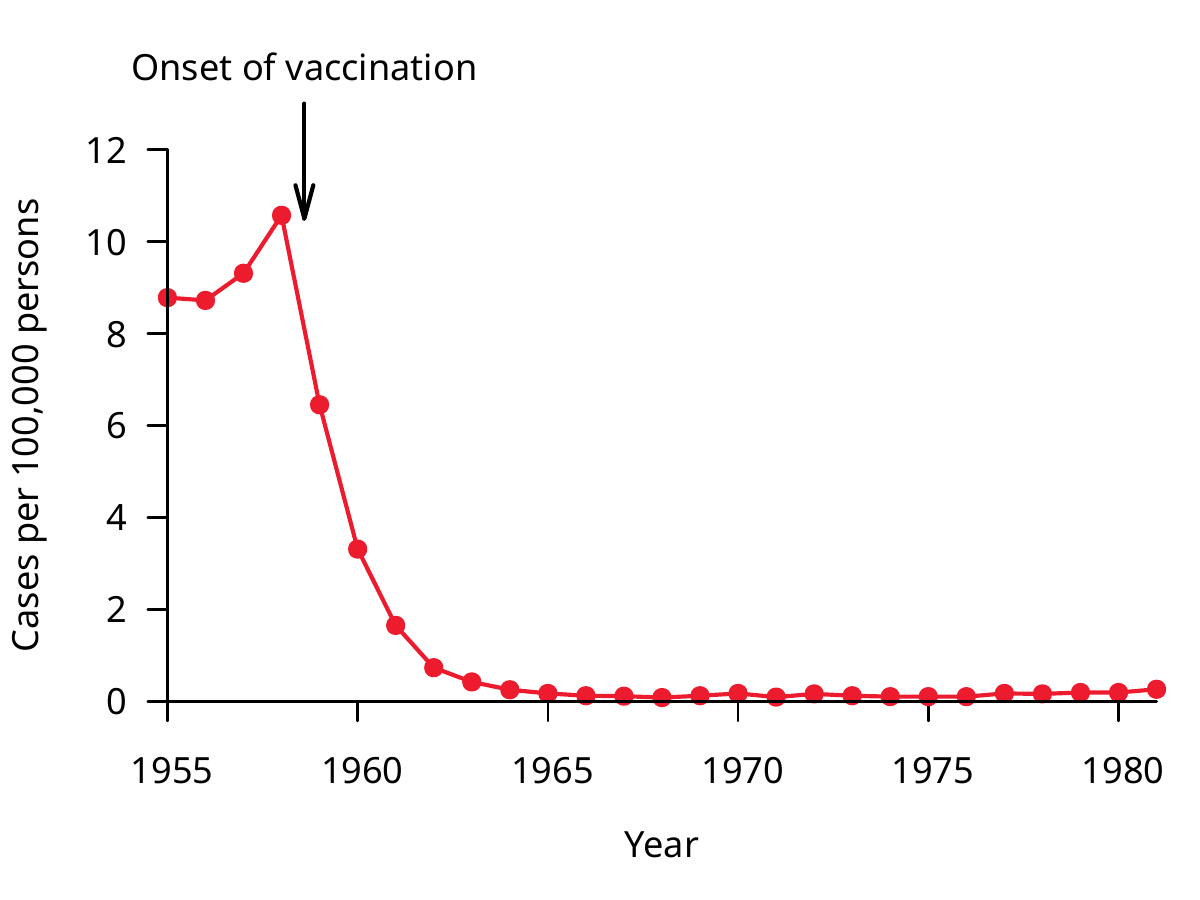

4.1. Acute polio cases per year in the USSR before and after vaccination

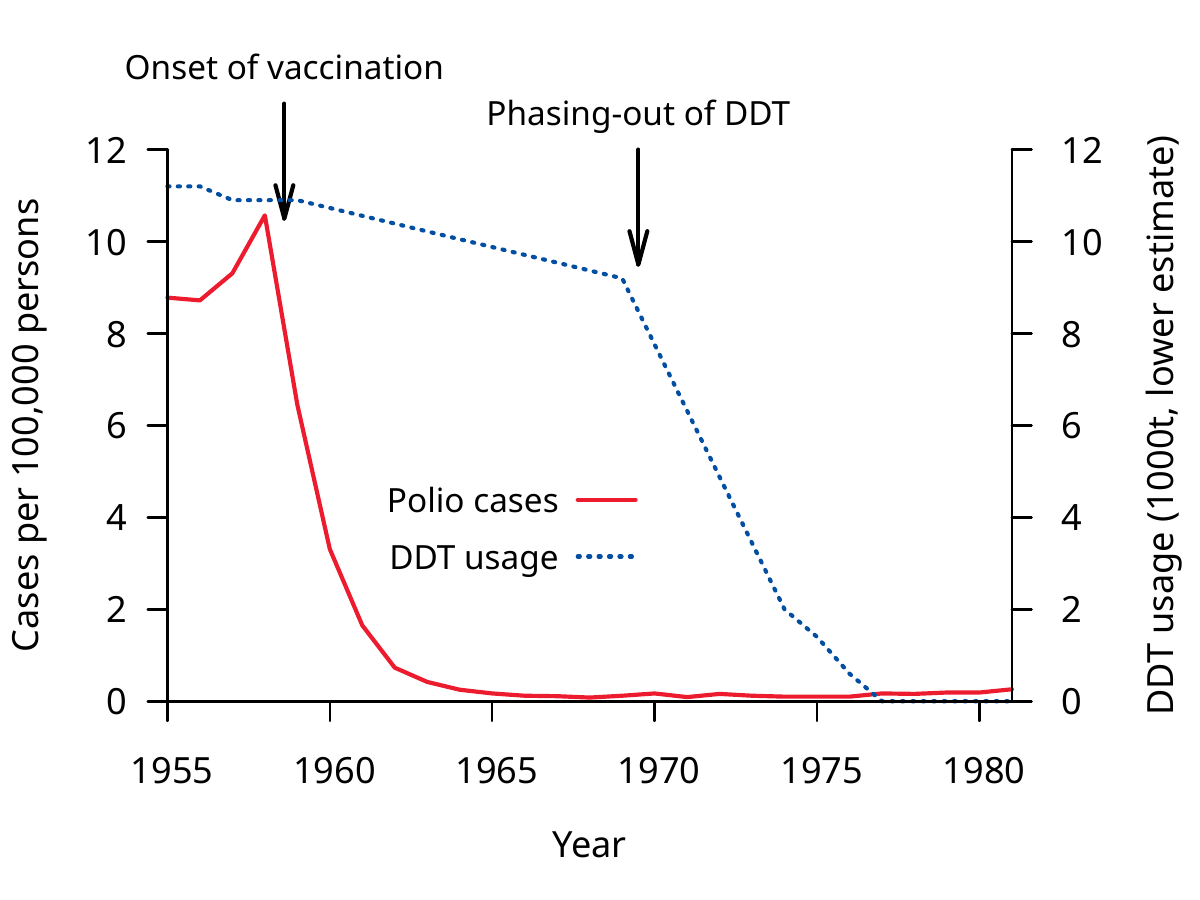

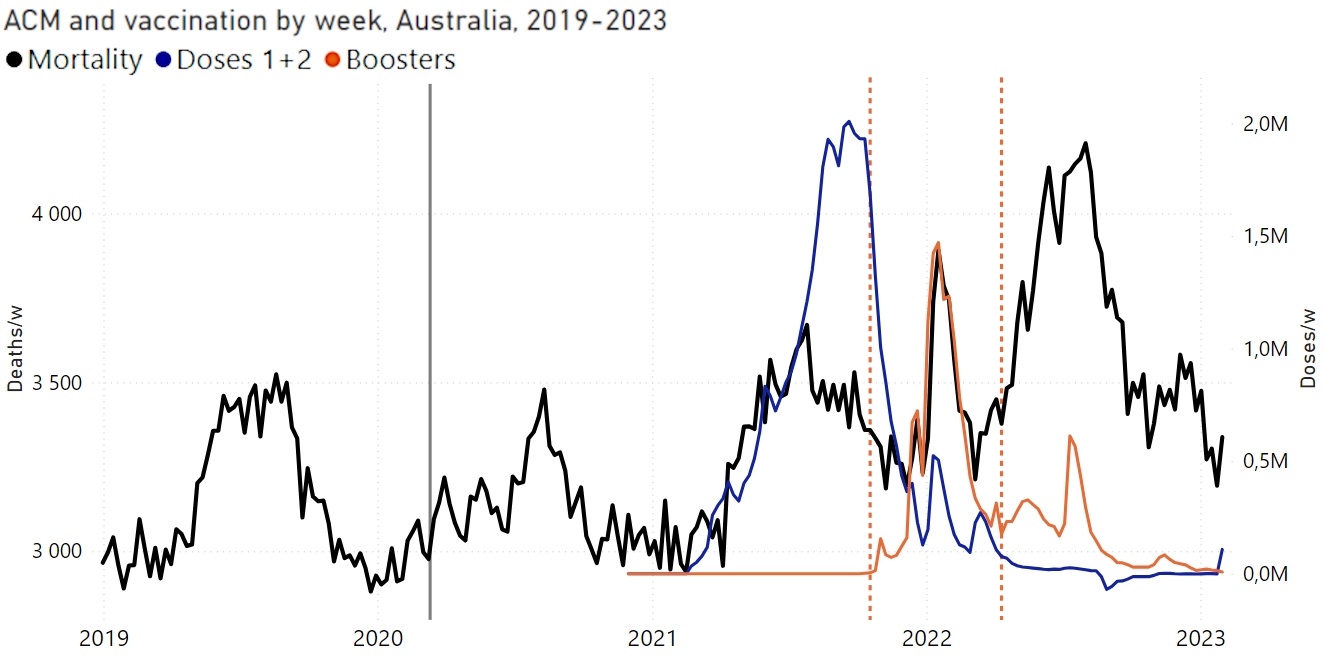

The outcome of the vaccination campaign that was begun halfway through the year 1959 is summarized in this graph from a later paper [11]: the annual incidence of the disease dropped sharply and stayed down during the two subsequent decades.

Considering the very high vaccination rate achieved already in 1960, one might wonder why the initial drop was not even steeper than apparent from this slide. While this question cannot definitely be answered from the studies at hand [9,11], this may have to do with increasingly strict diagnostic criteria: cases may have initially been diagnosed based on clinical findings alone, whereas in later years only cases confirmed by detection of the virus or specific antibodies may have been counted. Alternatively, the vaccine strains might have with time dislodged the circulating wild type poliovirus strains. A definite answer would likely require a thorough examination of the Russian medical literature.

4.2. Efficacy of live vs. inactivated polio vaccine

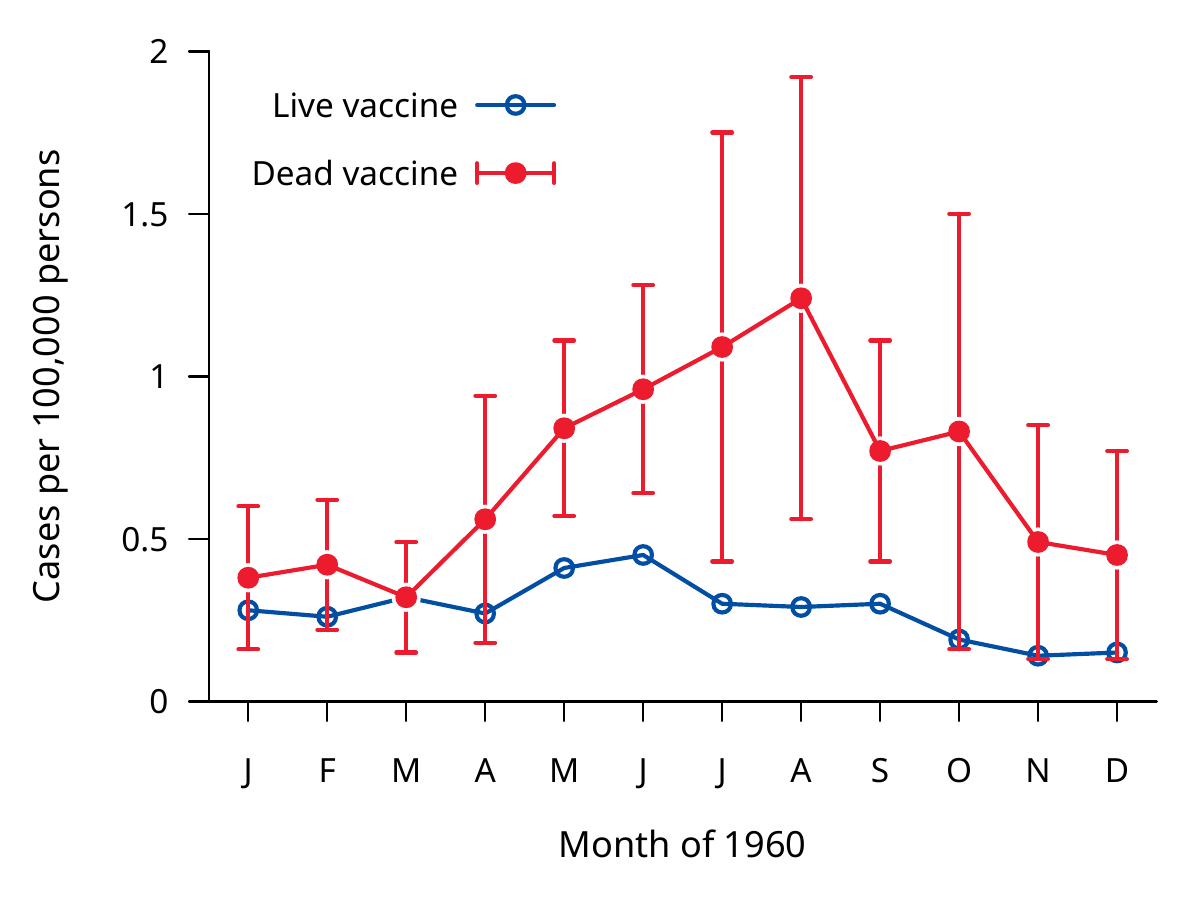

While most young persons in Russia had received the live vaccine, an inactivated vaccine was used for comparison in some administrative districts. The graph in this slide (from data given in [9]) shows that residual rates of polio remained distinctly higher in those districts, showing a clearly inferior efficacy of the inactivated vaccine. In fact, in the Krasnodar district, the case numbers in 1960 exceeded the national averages from the years before the vaccination campaign.

The lower (or even marginal) protective efficacy of the inactivated vaccine may have been due to excessive chemical treatment. At the time of this campaign, the Cutter incident in the U.S. had already occurred—an incompletely inactivated vaccine had given rise to paralytic disease in several hundred vaccinees. The Russian scientists may have erred on the side of caution by applying too aggressive chemical inactivation. This would have “mangled” the immunological features of the virus particles and rendered any antibodies induced by them largely ineffective against the unmodified virus.

Production methods for the inactivated vaccine have since improved, and other countries that have relied on this vaccine have obtained better results [12]. Nevertheless, the data in this slide show that “Turtles” and “Dissolving Illusions” are remiss in basing their evaluation of polio vaccine efficacy only on experiences with early inactivated vaccines from the 1950s.

5. Serious problems with polio vaccines

- Failed immunization or fading immunity

- Persons who have received the inactivated vaccine may still spread the wild-type virus

- Live vaccine virus may cause paralytic disease

- Inactivated vaccine may contain residual live virus, giving rise to paralytic disease

- Early batches of both live and inactivated vaccine were contaminated with the oncogenic monkey virus SV40

While though I consider the evidence of vaccine efficacy against polio conclusive, I do not mean to imply that there are no serious problems with the vaccines. In fact, I consider it unproven that any of these vaccines have produced a net benefit in overall health outcomes.

Failed immunization or fading immunity are more common with the inactivated vaccine, but infections with wild-type poliovirus strains leading to paralytic disease have occurred in live-vaccinated persons also. In principle, fading immunity can be overcome with booster injections, but such campaigns tend to have lower participation rates. This can leave sizable numbers of people without immunity and result in outbreaks of the wild-type polio.

One such outbreak occurred in Albania in the year 1996; it was reportedly stopped by subsequent mass vaccinations. In this outbreak, the age groups between 11 years and 35 years were preferentially affected [13]. It seems that these age groups had previously received vaccine that had been stored without refrigeration for several weeks.

5.1. Live virus vaccine and paralytic disease

- The live virus strains are attenuated, but in immunocompromised persons they may nevertheless cause paralytic disease (numerous cases reported, some fatal)

- Live vaccine virus strains may be transmitted from vaccinated to unvaccinated persons, including immunodeficient ones

- Serial transmission of vaccine virus can lead to mutations that give rise to increased neurovirulence

- There have been multiple outbreaks of poliomyelitis due to mutated vaccine virus strains

Even though the live vaccine virus strains are less virulent than the wild-type forms, a functioning immune system is nevertheless required to contain the infection with these vaccine viruses. In persons with genetic or acquired immune deficiencies, these attenuated strains can cause paralytic disease, sometimes fatal.

Immunocompromised people may also have difficulty clearing the infection. The prolonged replication in such persons gives the vaccine virus time to mutate and thereby revert to increased virulence. Such mutated strains may then be transmitted to the non-immune population at large. Multiple outbreaks due to mutant vaccine virus strains have indeed occurred [10,14,15]. Conceivably, such strains might actually perpetuate polio after a successful eradication of the wild-type strains.

5.2. SV40 contamination of early polio vaccine batches

From Fields Virology:

The next member of the [polyomavirus] family to be isolated was simian virus 40 (SV40) by Sweet and Hilleman in 1960. They were screening samples from poliovirus vaccine lots produced in rhesus monkey kidney cells for the presence of contaminating viruses. SV40 was the 40thvirus isolated in this screen …

From Sweet and Hilleman’s paper:

Hull et al. have studied extensively viruses encountered in “normal” monkey renal cell cultures. Hull called them simian or SV viruses … 28 of these viruses were precisely separated serologically into types and, additionally, 24 unidentified viruses were recorded.

… other viruses may also have been in some vaccine batches

The polyomavirus SV40 was present as a contaminant in early batches of both the live and the inactivated polio vaccines. It came from the monkey kidney cells that were used to grow up those vaccines. The standard text “Fields Virology” [16] offers a somewhat inaccurate version of these events, but the paper by Sweet and Hilleman it cites sets the record straight [17]. Even before these authors got involved, a large number of contaminating monkey viruses had been identified by Hull and coworkers.

While it seems that all of these scientists tried their best to prevent the release of contaminated vaccine batches, they had to rely, for the detection of so far unknown viral agents, on observing cytopathic effects in cell culture, i.e. of infected cells that look sick or die off. It seems that SV40 did not readily produce such cytopathic effects in the cell cultures used for screening those vaccine lots.

Sweet and Hilleman reported the repeated isolation of SV40 as early as 1960, yet nevertheless the virus remained in commercial vaccine batches for several years after that. It seems that this was covered up by the authorities.

5.3. SV40 and human health

- SV40 induced tumors in animal experiments

- Has been detected in various kinds of human tumors

- mesothelioma

- brain cancer

- bone cancer

- non-Hodgkin-lymphoma

- Statistical studies disagree on the correlation between polio vaccines and cancer

- Heinonen 1973 [18] found low absolute case numbers, but high relative risk of cancer among children exposed to inactivated vaccine in in utero

The association of SV40 with some human tumors seems to be uncontroversial, but some may still question the causal role of the virus in these tumors [19]. It is unclear to what extent SV40 in the polio vaccines has increased the risk of such cancers. Most statistical studies find no clear evidence of cancer risk due to these vaccines [20].

One study stands out, however, with respect to both its findings and the group of subjects investigated. Heinonen et al. [18] examined the overall risk of cancers in children who had been exposed in utero, i.e. their mothers had been injected with the inactivated vaccine during pregnancy. While the absolute case numbers of cancers in those children were not particularly high, the relative risk was significantly increased.

In this connection, we should note that other polyomaviruses are known to cause disease in immunocompromised patients. The JC virus causes progressive multifocal leukencephalopathy, a form of wholesale brain degeneration, whereas the BK virus causes a very destructive disease of the kidneys. Embryos and early fetuses, too, lack a functioning immune system; this makes them susceptible for example to severe damage by rubella virus, which after birth will only very rarely cause major disease. It is not implausible to assume that exposure to SV40 in utero may cause more widespread infection that, even though not manifesting as dramatically as rubella, may then give rise to cancer sometime after birth.

We might also wonder whether SV40 would be more prone to cause disease when contained in live vaccine than in the inactivated vaccine or vice versa. On the one hand, the live vaccine is not subject to chemical inactivation, so that contaminating viruses would more likely survive. On the other hand, since the live vaccine is not injected, such contaminating viruses would have to traverse the intestinal barrier. Thus, the question cannot be answered from a priori considerations. I am not aware of any thorough experimental investigation of this question.

6. DDT and Polio

As stated before, both “Turtles” and “Dissolving Illusions” maintain that, in its day, DDT was a major cause of epidemic poliomyelitis. We can use the Russian data to evaluate this claim.

6.1. DDT use in the USSR by region

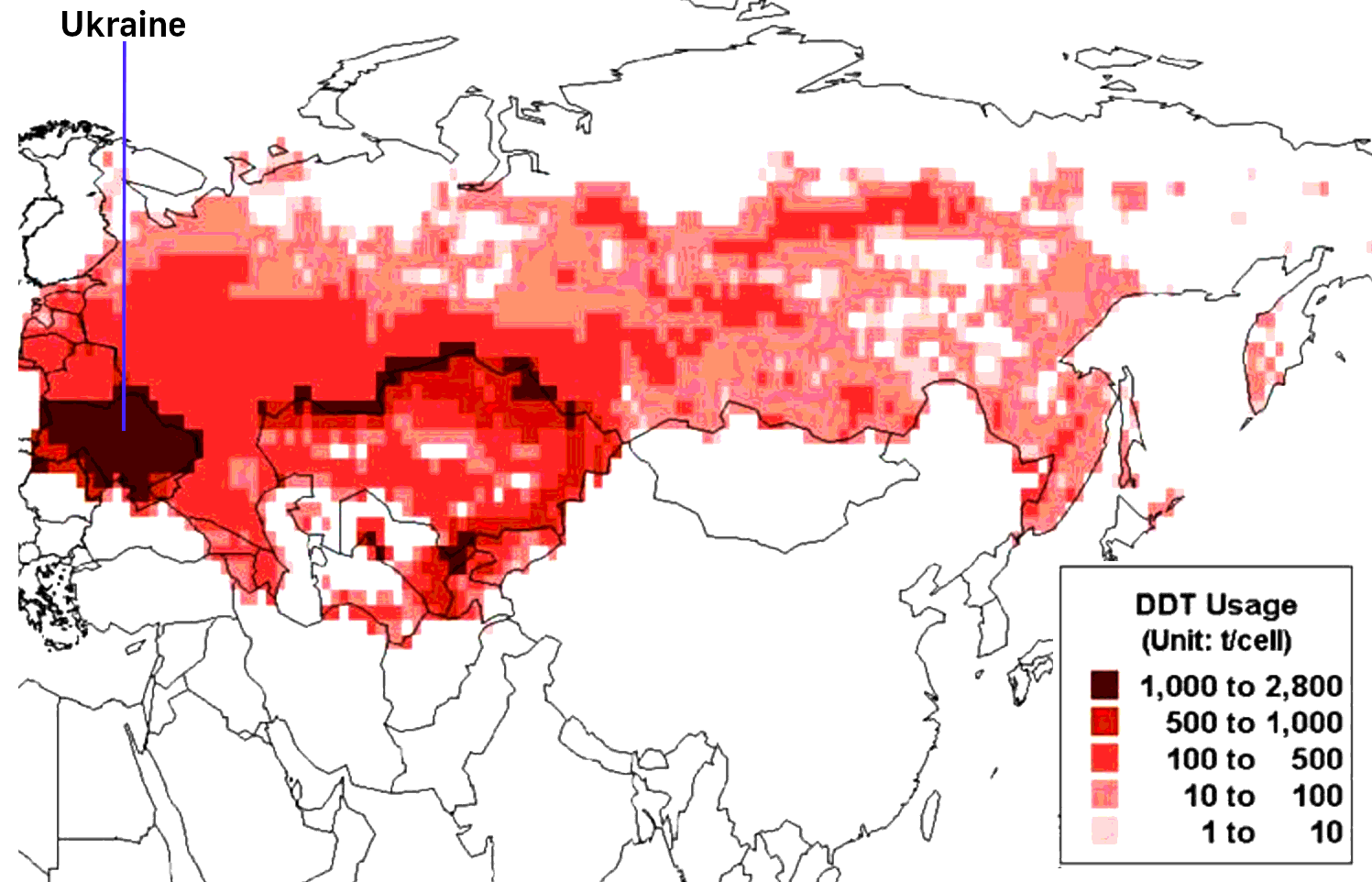

In the USSR, DDT was mostly used in agriculture. This graphic, taken from [21], shows the cumulative amounts used per unit area over the middle decades of the 20thcentury. Ukraine, when part of the former USSR, used to be that country’s richest and most fertile region, and accordingly this is where DDT was used the most extensively.

6.2. Polio in the Ukraine vs. USSR overall

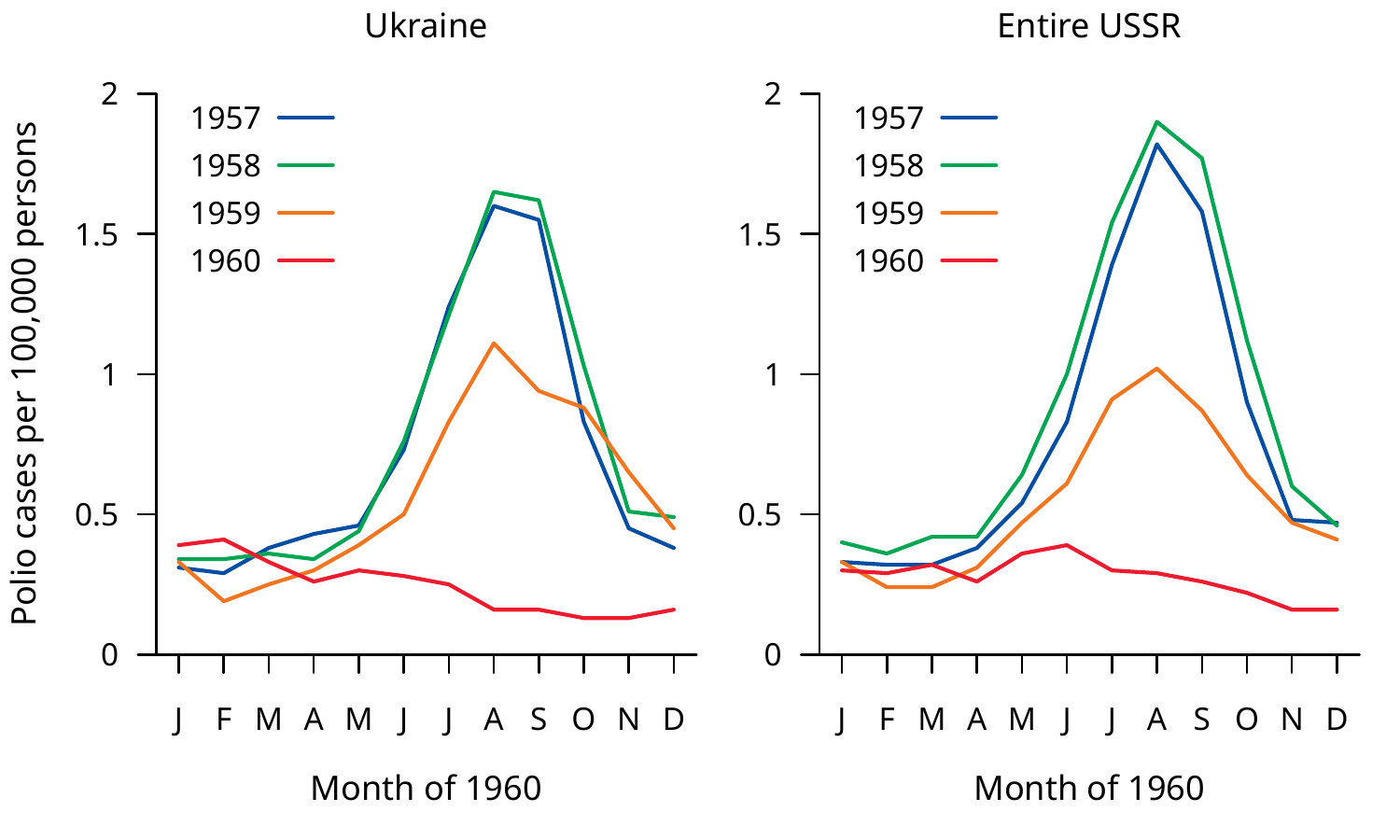

In keeping with the high amounts of DDT used in Ukraine, we should expect a higher incidence of polio in this area than in the remainder of the Soviet Union (and therefore than the national average). However, this slide shows that both before and after the onset of vaccination, the incidence in Ukraine closely tracked the national average [9].

6.3. Time course of polio incidence and of DDT use in the USSR

That DDT was not the cause or a major contributing factor to poliomyelitis is also evident from this slide, which compares the time course of polio incidence [11] to that of DDT use [21] in the Soviet Union.

Polio rates dropped precipitously immediately after the onset of vaccination, whereas DDT use continued on a high level for another decade before being phased out. When its use was finally terminated, this had no discernible effect on the already very low incidence of poliomyelitis.

6.4. “Dr. Biskind goes into battle”

“Turtles” quotes Dr. Morton Biskind to prop up its own story about DDT causing polio:

During a period of more than two years, numerous cases of a curious symptom complex, apparently never before reported … widely attributed to infection with a thus far illusory “virus.”

[22]The high incidence, the usual absence of a febrile reaction … suggested an intoxication rather than an infection … soon led to consideration of DDT.

[23]The title of this slide is taken directly from “Turtles.” Thus, the authors appoint Dr. Morton Biskind, posthumously, as the champion of their failed DDT hypothesis. However, a closer look at Biskind’s statements shows that he had implied nothing of the sort.

6.5. “Dissolving Illusions” and its interpretation of Biskind’s words

In the fear-baked summers of polio, many parents were totally unaware that exposure to DDT alone induced symptoms that were completely indistinguishable from poliomyelitis—even in the absence of a virus.

6.6. What is wrong with this picture?

- Biskind cites a combination of symptoms “never before reported”—but polio is clinically familiar

- Polio typically begins with a febrile infection, usually involving the GI tract (vomiting/diarrhea) and the meninges (headache etc.)—Biskind’s words “absence of a febrile reaction” do not describe polio

- The new “virus X” had been postulated precisely because these cases did not resemble polio or any other familiar infectious disease

- Biskind’s 1949 paper mentions poliomyelitis only once, in a footnote:

Needless to say, findings related to the nervous system, and muscular spasm and weakness in severe acute affections of this type have led to confusion with such entities as meningitis and poliomyelitis.

Biskind is clearly saying that DDT likely caused numerous cases of intoxication, which were mistaken by his colleagues not for polio but for a novel infectious disease. Only a few individual cases were conflated with familiar diseases such as meningitis or polio. Errors of this kind are always bound to happen, but Biskind accords them no more than a footnote.

“Dissolving Illusions” commits the same blunder as “Turtles”, citing Biskind’s 1949 paper as evidence for the following statement:

In the fear-baked summers of polio, many parents were totally unaware that exposure to DDT alone induced symptoms that were completely indistinguishable from poliomyelitis—even in the absence of a virus.

The meaning of Biskind’s words is clear enough, and it has no similarity to that which “Turtles” and “Dissolving Illusions” impute to them.

Correction: Zoey O’Toole, the translator and editor of “Turtles”, has pointed out to me that in some later papers Dr. Biskind indeed stated more clearly his suspicion that cases of DDT poisoning had been mistaken for polio:

When the population is exposed to a chemical agent [DDT] known to produce in animals lesions in the spinal cord resembling those in human polio, and thereafter the latter disease increases sharply in incidence and maintains its epidemic character year after year, is it unreasonable to suspect an etiologic relationship?

“Turtles” indeed cites the paper containing this statement, whereas “Dissolving Illusions” does not. While this correction invalidates my criticism regarding the use of Dr. Biskind as a witness, it does not validate the books’ scientific arguments.

7. Paralytic disease related to polio

Both books discuss poliomyelitis and clinically similar paralytic diseases, suggesting that such diseases somehow invalidate the conventional polio narrative. However, these insinuations are without foundation.

7.1. Poliomyelitis without poliovirus

- Several enteroviruses other than poliovirus have been shown to cause the same disease and lesions in the spinal cord

- Usually clinically milder than with poliovirus, but enterovirus 71 has proven highly neurovirulent in some outbreaks

- “Nonparalytic poliomyelitis” is not clinically characteristic—confusion on this point arises from confused nomenclature

The entire subject was lucidly reviewed by Sabin in 1981 [24], but neither book cites this outstanding paper. Sabin enumerates the enteroviruses that had at the time been found to cause poliomyelitis. Individual cases of this disease were clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from those caused by the “proper” poliovirus strains, but on average their clinical course tended to be milder.

In assessing the relative importance of these virus strains, one must take into account that polio vaccination has greatly reduced the incidence of disease caused by poliovirus, whereas no protection is available from these more recently discovered viruses. Thus, a significant contribution of novel viruses to overall disease remaining after the introduction of polio vaccines does not detract from the usefulness of those vaccines.

Our two books also try to make hay by pointing to the frequent failure of poliovirus isolation from clinically diagnosed cases of “non-paralytic poliomyelitis.” But this diagnosis is a misnomer—a contradiction in terms. “Poliomyelitis” really refers to a pathological finding, namely, an inflammation of the spinal cord’s gray matter that cannot fail to induce at least transient paralysis.

To avoid such confusion, Wickman had already proposed in 1907 the name “Heine-Medin disease” to comprise both paralytic and non-paralytic infections with the same (at the time still hypothetical) infectious agent [3]. It is unsurprising that, in the context of an ongoing polio epidemic, some cases of gastroenteritis or viral meningitis will initially be attributed to poliovirus, but then turn out to be due to other pathogens instead. The exact percentages of such mistaken clinical diagnoses have of course no bearing whatsoever on the actual significance of poliovirus.

7.2. Paralytic poliomyelitis in spite of vaccination

Several possible causes:

- Other neuropathogenic viruses (particularly enteroviruses)

- Failed immunization or fading immunity

- Other acute neurological diseases can be clinically difficult to differentiate, e.g. polyradiculitis (Guillain-Barré syndrome)

We have already touched on several of these causes. The live vaccine is applied orally and recapitulates the normal gastrointestinal infection, which also means that it is shed in the stool and can be transmitted to other persons, much like the wild-type strains of poliovirus. As noted earlier, this can give rise to mutant vaccine strains that revert to higher virulence. It also poses a problem in connection with immunodeficient individuals, who may become exposed not only by being vaccinated themselves, but also indirectly due to the shedding of vaccine virus by other persons.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (polyradiculitis) can be difficult to distinguish from poliomyelitis, although a combination of virological, immunological and electrophysiological tests (and if necessary nerve biopsies) should resolve most clinically ambiguous cases. The disease is due to cross-reactive autoimmunity that is triggered by natural infections, but also by vaccinations, including those against polio.

If one aims for a valid risk-benefit analysis of polio vaccination, the disease forms listed here must certainly be taken into consideration. Alas, neither “Turtles” nor “Dissolving Illusions” attempt such a balanced evaluation.

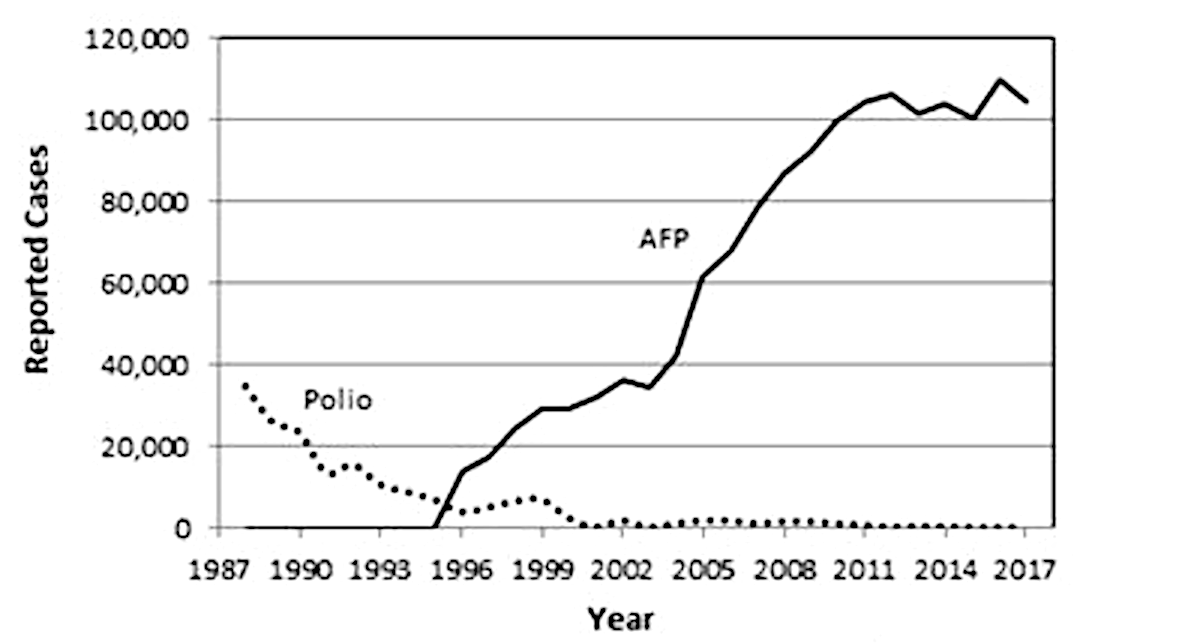

7.3. Polio and “acute flaccid paralysis”—globally reported cases 1988-2017

This chart is shown as Figure 10.3 in “Turtles.” The book comments on the findings as follows:

The number of cases of non-polio acute flaccid paralysis has been steadily rising, in parallel with the decrease in polio incidence.

The subtext is that, since poliovirus (according to “Turtles”) is not the cause of poliomyelitis, “acute flaccid paralysis” (AFP) is merely a new name for the disease formerly known as polio. However, the following observations are in order:

- The graph merely shows globally reported cases; there is no way of knowing for certain what the incidence of unreported cases of AFP was in earlier years.

- AFP is a broad clinical category, but individual cases can be more exactly attributed to Guillain-Barré syndrome, true poliomyelitis, and other causes. There is no need to speculate.

- If we take the graph at face value, then it is clear that AFP took off not “in parallel with the decrease in polio incidence” but only after polio had already dropped to near zero.

As with their DDT story, it is obvious that the authors of “Turtles” cannot see past their own preconceived notions and look at the data without prejudice.

8. Is poliomyelitis really a disease of civilization?

- In the west, did polio really become prevalent/epidemic only in the 20thcentury?

- In colonial settings etc., did polio really affect westerners more than the local populations?

- Are noble savages really protected from poliomyelitis?

The idea of polio as a disease of civilization pervades much of the literature on the disease, and, needless to say, our two books enthusiastically run with it. But does it stand up to scrutiny?

8.1. Findings reported by Jabob Heine in 1860

- German MD orthopedist, first physician to systematically study the disease

- Treated 192 poliomyelitis patients in his own clinic, achieving significant clinical improvement in many cases

- Regarding the prevalence of the disease, he noted (my translation):

[The disease] may properly be called widespread, and not only in our part of the world … such sudden paralysis in small and otherwise healthy children also frequently occurs in India, and we hear similar reports from Egypt and other non-European countries. Another author, Colmann, even mentions that it occurs epidemically … also, almost all paralytic deformations that date from childhood belong to this form of paralysis.

Among the very limited sources on poliomyelitis from the 19thcentury, the monograph “Spinale Kinderlähmung” [25] by Jacob Heine stands out. Heine was the first physician to make this disease his main focus of study, and according to his own reports he had considerable success in treating (and sometimes curing) residual paralysis. His quoted words, as well as the very considerable number of patients in his own care, do not encourage the idea that the disease was less common in his day than 100 years later.

Another case in point is the Swedish epidemic studied by Wickman—even though it had occurred a little later, shortly after the turn of the century. In this epidemic, the incidence had been higher in the rural farming communities than in the cities, again giving no indication that modernity was somehow responsible for spreading the disease.

A more plausible explanation for the perceived increase in importance of polio is the greatly diminished incidence of other childhood diseases—polio came to the fore simply by not being likewise diminished.

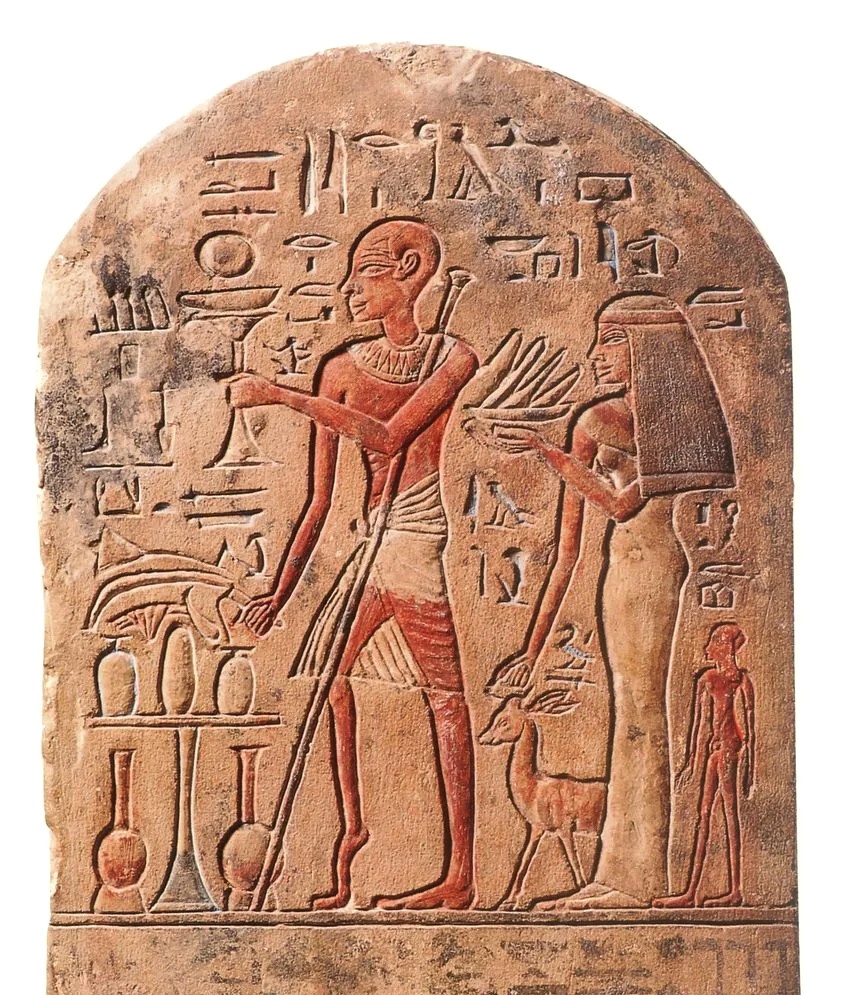

8.2. An apparent case of polio on a stele from ancient Egypt

This Egyptian stele has been dated to about 1500 years B.C. It shows the guardian of the temple of the goddess Astarte, with his wife and son. The atrophy and deformity of his right leg are of course merely suggestive of polio. However, there is a good number of skeletons dating from antiquity and the middle ages with deformities that have been ascribed to polio by the anthropologists who have studied them [26].

8.3. Albert Sabin on polio incidence in China

In 1946, I investigated an outbreak of poliomyelitis among U.S. Marines in Tientsin, China. I was told at the time that paralytic poliomyelitis was extremely rare in China. Some years later, Ku Fang-chou et al. reported a very high incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis in Tientsin, Shanghai, and Tsingtao in 1957-1959 … the average annual rates of reported paralytic cases of 144, 263, and 353 per million total population in these three cities was higher than the ~135 reported paralytic cases per million total population in the United States during the 1951-1955 prevaccine era.

Sabin, a medical man of outstanding ability, dedicated his life’s work to understanding and fighting poliomyelitis. Toward the end of his career, he came to the conclusion that “much of the dogma about paralytic poliomyelitis in the tropics was based on obviously incomplete reporting” [24].

8.4. That leaves the noble savages …

“Dissolving Illusions” cites a study by Neel et al. [27], concerning the isolated Brazilian Xavante tribe:

The paradox of a virtual absence of paralytic poliomyelitis among such heavily infected groups as this, despite high antibody titers, is well known, but the interpretation of the observation remains under discussion.

But how profound is the mystery, really?

- Neel reports that “there are today between 1500 and 2000 Xavante, living in a number of autonomous communities along the Rio das Mortes …”

- Assuming the same incidence as in the US before vaccination, there should be about 0.2 to 0.25 new cases per year

Neel also mentions that the study was “carried out during the summer of 1962,” i. e. it lasted less than a year. Therefore, even considering that poliomyelitis is more common in the summer than in the winter—but such seasonality is less pronounced in warmer climates—the above numbers mean that Neel’s chances of witnessing any acute cases at all would have been quite low.

As to the prevalence of persistent paralysis, the vagueness of his population estimate (“between 1500 and 2000”) strongly suggests that he did not make a close first-hand survey of that population, which might have acquainted him with any such cases. Thus, no mystery remains to be explained or explained away.

9. Summary

Both books

- present important facts and problems with polio vaccines

- … but weaken their own case by not offering a balanced perspective

- don’t acknowledge the effectiveness of the live vaccine

- push a wrong-headed idea of disease causation by DDT, which conforms to naive environmentalist prejudice but does not withstand scrutiny

- obsess over “epidemiological enigmas” that have no solid basis in fact

While both books present important information on polio vaccines that must be part of any valid risk-benefit analysis, neither offers a balanced, realistic overall perspective. Thus, these books should not be relied upon as the sole sources of information in making decisions for or against polio vaccination.

Notes

References

- Humphries, S.A.B.R. (2013) Dissolving Illusions: Diseases, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History (CreateSpace).

- Anonymous (2022) Turtles All The Way Down: Vaccine Science and Myth (Children’s Health Defense/Skyhorse Publishing).

- Wickman, I. (1907) Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Heine-Medinschen Krankheit (Karger).

- Trask, J.D. and Paul, J.R. (1941) Experimental Poliomyelitis In Cercopithecus Aethiops Sabaeus (The Green African Monkey) By Oral And Other Routes. J. Exp. Med. 73:453-9

- Horstmann, D.M. et al. (1947) The Susceptibility Of Infant Rhesus Monkeys To Poliomyelitis Virus Administered By Mouth : A Study Of The Distribution Of Virus In The Tissues Of Orally Infected Animals. 99 86:309-23

- Howe, H.A. and Bodian, D. (1948) Poliomyelitis in the cynomolgus monkey following oral inoculation. Am. J. Hyg. 48:99-106

- Gebhardt, L.P. and Bachtold, J.G. (1953) Reproducible oral infection rates in monkeys with the Mahoney strain (Type 1) of poliomyelitis virus. 431 83:807-9

- Landsteiner, K. and Popper, E. (1909) Übertragung der Poliomyelitis acuta auf Affen. Z. Immunitätsforsch. 2:377-393

- Chumakov, M.P. (1961) Some results of the work on mass immunization in the Soviet Union with live poliovirus vaccine prepared from Sabin strains. Bull. World Health Organ. 25:79-91

- Burns, C.C. et al. (2013) Multiple Independent Emergences of Type 2 Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses during a Large Outbreak in Northern Nigeria. 377 87:4907-4922

- Grachev, V.P. (1984) Long-term use of oral poliovirus vaccine from Sabin strains in the Soviet Union. 2861 6 Suppl 2:S321-2

- Axelsson, P. (2012) The Cutter incident and the development of a Swedish polio vaccine, 1952-1957. Dynamis 32:311-328

- Prevots, D.R. et al. (1998) Outbreak of paralytic poliomyelitis in Albania, 1996: high attack rate among adults and apparent interruption of transmission following nationwide mass vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:419-25

- Etsano, A. et al. (2016) Environmental Isolation of Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus After Interruption of Wild Poliovirus Transmission – Nigeria, 2016. MMWR 65:770-3

- Korotkova, E.A. et al. (2016) A Cluster of Paralytic Poliomyelitis Cases Due to Transmission of Slightly Diverged Sabin 2 Vaccine Poliovirus. J. Virol. 90:5978-88

- Knipe, D.M. and Howley, P.M. (2013) Fields Virology (Wolters Kluwer).

- Sweet, B.H. and Hilleman, M.R. (1960) The vacuolating virus, S.V. 40. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 105:420-7

- Heinonen, O.P. et al. (1973) Immunization during pregnancy against poliomyelitis and influenza in relation to childhood malignancy. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2:229-35

- Ferber, D. (2002) Virology. Monkey virus link to cancer grows stronger. Science 296:1012-5

- Dang-Tan, T. et al. (2004) Polio vaccines, Simian Virus 40, and human cancer: the epidemiologic evidence for a causal association. Oncogene 23:6535-40

- Li, Y.F. et al. (2006) Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane usage in the former Soviet Union. Sci. Total Environ. 357:138-45

- Biskind, M.S. (1949) DDT poisoning and elusive virus X; a new cause for gastro-enteritis. Am. J. Dig. Dis. 16:79-84

- Biskind, M.S. (1951) Statement on clinical intoxication from DDT and other new insecticides. J Insur Med 1946 6:5-12

- Sabin, A.B. (1981) Paralytic poliomyelitis: Old dogmas and new perspectives. Rev. Infect. Dis. 3:543-64

- von Heine, J. (1860) Spinale Kinderlähmung (Cotta).

- Berner, M. et al. (2021) Challenging definitions and diagnostic approaches for ancient rare diseases: The case of poliomyelitis. Int. J. Paleopathol. 33:113-127

- Neel, J.V. et al. (1964) Studies On The Xavante Indians Of The Brazilian Mato Grosso. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 16:52-140