| 15 |

Panama: results from sanitation |

| 15.1 |

Lowering of the general death rate |

Every month full details are published of the health of the Canal zone and of the cities of Colon and Panama, as well as statistics of the amount of sanitary work done; and the monthly reports are condensed into the annual reports, which are also published. From them it is possible to follow, from year to year, the improvement in the health of the inhabitants, and the success of the sanitary work. In addition to that in the reports, information can be obtained from many of the papers published by individual members of the Sanitary Department: and I am indebted to Colonel Phillips, acting chief sanitary officer, for certain other information hitherto unpublished.

| Year | Number of employees | Deaths | death rate per 1000 |

| 1904 | 6,213 | 82 | 13.26 |

| 1905 | 16,512 | 427 | 25.86 |

| 1906 | 26,547 | 1,105 | 41.73 |

| 1907 | 39,238 | 1,131 | 28.74 |

| 1908 | 43,891 | 571 | 13.01 |

| 1909 | 47,167 | 502 | 10.64 |

| 1910 | 50,802 | 558 | 10.98 |

| 1911 | 48,876 | 539 | 11.02 |

| 1912 | 50,893 | 467 | 9,18 |

| 1913 | 56,654 | 473 | 8.35 |

Broadly, the results summarized in Table 15.1 bring out how for the first two and a half years of the American occupation the death rate increased along with the increase of the labour force; but that since 1906 there has been a steady improvement, and this although the labour force increased much more rapidly than in the previous period. This remarkable improvement is due to a reduction in the death rate from all diseases. In Table 15.2 the number of deaths from special diseases is not shown as a rate per thousand, but the actual number of deaths is given.

| Disease | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 |

| Typhoid fever | 12 | 42 | 98 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 4 |

| Dysentery | 14 | 69 | 48 | 16 | 8 | 21 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| Pneumonia | 95 | 413 | 328 | 93 | 70 | 73 | 94 | 57 | 47 |

| Malaria | 86 | 233 | 154 | 73 | 52 | 59 | 47 | 20 | 21 |

Not only have the employees on the zone benefited by the work of the Sanitary Department, but so have the cities of Panama. And Table 15.3 answers the question: Does Sanitation Pay? The answer is that it does pay in lives saved; but to consider the gain only from this point is to fail to realise that, but for the improved health, it would never have been possible to gather together, or keep together if gathered, the great labour force necessary for the construction of the Canal.

| 15.2 |

The labour problem in 1906 |

Some conception of how serious the labour problem was will be found in a report made by Colonel Goethals when he first took charge. The report is relative to giving the Canal work out on contract, and says:

The Panama Canal presents a piece of work unprecedented in magnitude, which must be done under conditions entirely different from similar classes of work in the United States. The work naturally divides itself into dredging, dry excavation, the construction of the locks and dams, and the construction of the new Panama railroad. There is no contractor, or syndicate of contractors, that by any combination could bring to the Isthmus an organization ready for team work on any of these units. From the United States the supply of labour is the same whether the work be done by contract or by the Government, and the character of the labour must be the same.

So long as work is plentiful, the dread of the tropics will deter men from seeking work here in preference, and this is equally applicable lo the contractor and the Government. An adequate supply of labour from the United States is not possible. The records here show that no contractor can even attempt to recruit labour in the West Indies, and that great opposition will develop to any recruiting by authorized agents of the Commission if the labour procured is turned over to the contractors. These island governments cannot be blamed for their hostility towards the latter, because of their experience under the French, which left an indelible impression throughout the islands.

Conditions on the Isthmus are peculiar. It is contended, apparently on reasonable grounds, that service in the tropics saps the energy, and that a man is incapable, after a time, of performing the same amount of work that he could be able to accomplish had he spent the same time in a cooler climate. This creates a desire to accumulate sufficient means to avoid the necessity of relatively harder work on the return to the United States, and it is a question that the contractor would be obliged to face, as well as the United States. The wage scale on the Isthmus is practically adopted, and a contractor would be obliged to maintain it.

No account has been taken of the question of sanitation, one very important to the successful prosecution and completion of the work on the Canal. Proper sanitation can be maintained more easily and satisfactorily with the Government in supreme control of the work, than with the contractor. The relative advantages of the contract system versus hired labour under government supervision are very different today from what they were two years ago. To one familiar with conditions on the Isthmus there can be no doubt at this stage of the work as to the advisability of continuing it with hired labour.

| Year | Population | Death rate per 1000 | Lives saved |

| 1904 | 35,000 | 52.45 | – |

| 1905 | 56,624 | 49.94 | 142 |

| 1906 | 73,264 | 49.10 | 299 |

| 1907 | 102,133 | 33.63 | 1,922 |

| 1908 | 120,133 | 24.83 | 3,317 |

| 1909 | 135,180 | 18.19 | 4,631 |

| 1910 | 151,591 | 21.18 | 4,740 |

| 1911 | 156,936 | 21.46 | 4,683 |

| 1912 | 146,510 | 20.49 | 4,682 |

| Total lives saved for eight years | 24,596 | ||

Up to 30th June 1906 most of the labour on the Canal was drawn from the West Indian peoples, but as it was unsatisfactory from many points of view, labourers were brought from Spain. The Report of the Commission for 1906 says:

Another year’s experience from near-by tropical islands and countries has convinced the Commission of the impossibility of doing satisfactory work with them. Not only do they seem to be disqualified by lack of actual vitality, but their disposition to labour seems to be as frail as their bodily strength. Few of them are steady workers. The majority of them just work long enough to get money to supply their actual bodily necessities, with the result that while the Commission is quartering and caring for about 25,000 men, the daily effective force is many thousands less. Many of them settle in the jungle, building little shacks, raising enough to keep them alive, and working only a day or two occasionally, as they see fit. In this way, by getting away from the Commission’s quarters, practical control over them is lost, and it becomes very difficult for foremen to calculate on keeping their gangs filled.

The experiment with labourers from northern Spain has proved very satisfactory. Their efficiency is not only more than double that of the negroes, but they stand the climate much better. They have malaria in about the same degree as the white Americans, but not at all to the extent the negroes have it. Their general condition is about as good as it was at their homes in Spain. The chief engineer is convinced by this experiment that any white man so called under the same conditions will stand the climate on the Isthmus very much better than the negroes, who are supposed to be immune from practically everything, but who, as a matter of fact, are subject to almost everything.

Even in 1907 the Commission reports:

The labour problem is still an unsolved one, but the experiment of the last year with a diversity of races and nationalities has improved the efficiency of the force and promises to make the term of service longer. Tropical labour is migratory, and notwithstanding superior wages, housing, and subsistence, there will always be large periodical changes in the individual force. A regular recruiting organization, changed from one labour centre to another, will always be necessary to keep a maximum force available.

| 15.3 |

The Composition of the Labour Force |

By 1908 the problem had been solved. In two years the labour force had jumped from 26,000 to 43,000, and the death rate had fallen from 41 to 13 per 1000. From that time labour, as plentiful as the Americans could wish, has poured into the zone. Consisting of three different races who have shown different powers of resistance to disease, a detailed knowledge of the inhabitants of the zone and their habits is necessary for a full appreciation of the sanitary work. As this subject is very carefully considered by Drs Deeks and James in the report to which I previously alluded,69 I cannot do better than extract in extenso from that report:

The Racial Distribution of the Employees of The Canal Commission and their Manner of Living

Since the American occupation of the Canal zone, its inhabitants may be divided into two groups; the one composed of those who work for the Isthmian Canal Commission (referred to hereafter as the Commission), the other made up of natives of the country, with such immigrants as have been attracted by the increase in business. Upon the number and racial distribution of the persons included in the first group are based the data set forth subsequently. This group comprises three distinct races: the American, which is Anglo-Saxon in origin; the European made up mostly of Spanish and Italian labourers, with a considerable preponderance of Spaniards; and the West Indian negro, coming in greater part from the islands of Jamaica and Barbados. The numerical ratio between the two races, the time of residence in this country of the individuals who comprise them, and the relative susceptibility of each race to disease, must be kept constantly in mind, for these factors render complicated any attempt to compile reliable statistics that pertain to the total distribution of disease in this country. Two sets of figures are necessary, the one showing the total disease for all races, the other, totals for the separate races. And as far as possible such figures have been obtained. The second group, that of natives and non-employees, is of importance only in so far as it acts as a means of conveyance of disease to the first; the prevalence of disease in it does not affect to any appreciable extent the figures used in the subsequent tables and charts.

These three races are natives of localities where, broadly speaking, malaria does not prevail to any great degree. The Italians are mostly from the north of Italy; the Spaniards from the north of Spain, and Jamaica is not badly infected with malaria, while Barbados is said to be free from endemic cases. Such immunity against malaria, as is present during the earlier part of a residence here, is therefore racial and not acquired. How much of such immunity exists will be shown later. It is sufficient at present to say that Americans and Europeans alike are susceptible to the disease, while the negro possesses a partial racial immunity.

The same general conditions of sanitation, such as drainage, water supplies, sites from which grass and under-brush are removed, and inspection of quarters by the Department of Sanitation, obtain equally among the three races. But it is impossible to equalise the racial appreciation of such important individual sanitary measures as care of screening, predisposition to cleanliness, prophylactic use of quinine, and personal regard for health. These latter vary greatly among the races, and are directly responsible for the prevalence of malaria in proportion to racial susceptibility to the disease.

The American employees of the Commission are skilled mechanics, clerks, foremen, responsible railroad employees, civil engineers, physicians, and nurses, and others who fill the many positions connected with the executive, constructive, and administrative functions of the Canal building. Since January 1906, almost without exception, they have lived in houses provided by the Commission. These houses are equipped with screen doors, screened windows and verandahs, and are well kept by their inhabitants, any defects in the screening or the plumbing being reported promptly. Among these employees the use of quinine at the first onset of fever is universal, and prompt consultation with the nearest Commission physician is the rule. Each employee is granted six weeks’ vacation, with pay, for twelve months’ service, and this vacation must be taken in the States or in a malaria-free country. If a bachelor is too ill to work, he is sent to the Commission hospital at Ancon or Colon, and most married men who, by reason of sickness, are unfit for duty, also avail themselves of the hospital service. A sanatorium for convalescent patients is maintained in the malaria-free island of Taboga, in the Gulf of Panama. The Americans do not frequent at night the native quarters in the zone towns; do not expose themselves unnecessarily to malaria infection, and of their own initiative aid greatly in preserving their health and in keeping sanitary regulations. Classed with Americans, who are also called “gold” employees, are those white men of other nationalities who hold positions entitling them to similar quarters and treatment.

Those of the European labourers who so desire live in well-kept and carefully screened barracks, and for families, screened quarters are provided. But no amount of advice seems to be effective in securing among them individual prophylaxis against disease. Every sanitary regulation needs to be rigidly enforced. They often prefer to sleep in hammocks or even on the ground under their quarters or in other places. They mingle freely at night with the natives, and cannot be kept indoors. As a race they are not addicted to strong liquor, but we are informed by Mr Le Prince, the chief sanitary inspector, than an increase in malaria among them is always accompanied by an excessive consumption of rum, and very inferior rum, in the belief that the drink is an efficient medicine. They are indifferent to personal hygiene, and equally indifferent to their state of health, until illness compels them to seek aid.

As elsewhere in the world, the enforcement of sanitation among the negroes is a gigantic task. A small percentage only of this race live in the free quarters provided by the Commission. The rest either prefer cheap lodging houses, where they huddle together at night like so many sheep, or else they live in straw-thatched huts after the manner of the natives. The European labourer, though he mingles with the natives, does not live with them; but the negro lives and sleeps in their houses, exposing himself constantly to the endemic malarial infection there prevalent. As long as he has a roof over his head and a yam or two to eat, he is content, and his ideal of personal hygiene is on a par with his conception of marital fidelity.

| Year | Injury | Malaria | Other diseases | Total for disease | |

| Employees from the U.S. | 1907 | 2.56 | 1.16 | 6.05 | 7.21 |

| 1908 | 2.20 | 1.10 | 4.38 | 5.48 | |

| 1909 | 2.33 | .17 | 4.28 | 4.45 | |

| 1910 | 2.63 | .00 | 3.13 | 3.13 | |

| 1911 | 2.16 | .66 | 2.32 | 2.98 | |

| 1912 | 1.79 | .32 | 3.73 | 4.05 | |

| Other white employees | 1907 | 6.82 | 4.68 | 10.14 | 14.82 |

| 1908 | 9.68 | 5.20 | 3.47 | 8.67 | |

| 1909 | 4.30 | 3.84 | 4.14 | 7.98 | |

| 1910 | 7.06 | 2.16 | 2.88 | 5.04 | |

| 1911 | 6.43 | 3.53 | 4.82 | 8.35 | |

| 1912 | 5.00 | 1.41 | 4.06 | 5.47 | |

| Colored employees | 1906 | – | 7.80 | – | 49.01 |

| 1907 | 3.60 | 4.15 | 25.53 | 29.68 | |

| 1908 | 3.52 | .98 | 8.25 | 9.23 | |

| 1909 | 2.93 | .73 | 7.18 | 7.91 | |

| 1910 | 3.23 | .93 | 7.46 | 8.39 | |

| 1911 | 3.11 | .57 | 7.67 | 8.24 | |

| 1912 | 2.61 | .23 | 6.70 | 6.93 |

| 15.4 |

The racial death rates |

It was impossible to obtain the full figures relating to each race for 1906, for in that year the statistics of the Europeans were not separated from those of the Americans; but Major Noble was good enough to give me an interesting table on the annual death rates among Canal Commission employees, broken down according to ethnic groups (see Table 15.4).

A glance at these tables shows that the death rate of the American is lower than that of the other white races (Europeans, Spaniards, etc.), or of the coloured employees (black). Next to Americans come the Europeans.

When we look at the death rates from malaria, again the Americans come out lowest; but we now find that although the total death rate of the blacks is higher than that of the Europeans, their death rate from malaria is lower. This may seem strange when we remember that, although careless in their habits, most of the latter live in screened houses, while the negro is hardly at all protected; but the explanation is that a large proportion of the blacks come from malarious islands, and have acquired in infancy a certain amount of immunity to malaria. There are no statistics actually demonstrating the different incidence of malaria among the various black races, but Dr Darling gave me a striking piece of indirect evidence.

As is well known, all of the West Indian islands are malarious except Barbados, and were statistics available there can be no doubt it would be found the Barbadians were the chief sufferers from malaria. There are, however, statistics relating to blackwater fever, which is recognized to be in some way connected with malaria. Dr Darling gave me the following note on the cases which came to autopsy:

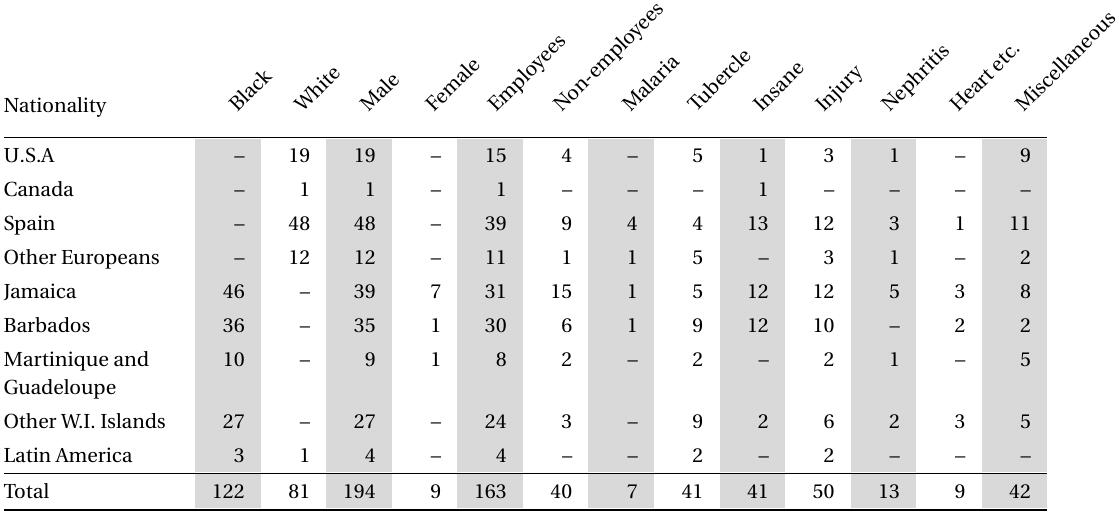

Haemoglobinuric fever has occurred among the blacks as well as the whites, although to a less extent; there is a marked preponderance of cases among negroes from Barbados, and relatively few from the other islanders. It is well known that Barbados is the only one of the West Indies free from malaria. The following table [Table 15.5] shows the nativity incidence of haemoglobinuric fever.

Very respectfully, S. T. Darling (Chief of Laboratory).

| Costa Rica | 1 | St Lucia | 2 | |

| Monserrat | 1 | Mexico | 1 | |

| Antigua | 1 | Grenada | 1 | |

| Guadaloupe | 1 | Jamaica | 2 | |

| Madeira | 1 | Barbados | 83 |

| 15.5 |

Pneumonia |

On the other hand, the coloured races are very susceptible to pneumonia, and this disease carried off large numbers in 1906 and 1907. By 1908 it had become much less prevalent, and one of the most interesting questions is: Did pneumonia disappear as the result of the negro’s obedience to sanitary orders, or because he refused to be controlled?

It is now recognized that malaria, by lowering the resistance of a population, raises the death rate from all causes, and the experience in India as well as elsewhere has been that pneumonia and malaria are often connected. Drs Deeks and James have shown that the seasonal curve of the two diseases in 1906 and 1907 was not the same; and that after 1907, while malaria although diminished retained its seasonal increases, yet pneumonia, although diminished, was very irregular, and not seasonal in incidence.

It has been suggested by Colonel Gorgas, I think, that the pneumonia disappeared partly because the negroes left the Commission quarters and went to live in isolated “shacks.” In other words, that being more scattered, the disease had less chance of spreading by contact. This is very probable; but it is no less probable that the general resistance of the negro having been raised by the diminution of malaria, pneumonia has no longer been able to attack him unless he were peculiarly susceptible. When less than 100 cases occur per annum in a labour force of over 40,000 people, it is not to be expected that any seasonal curve of value can be worked out, or that any great connection between it and malaria can now exist.

The connection between malaria and pneumonia is one of practical interest, and at the time pneumonia was so prevalent, an investigation was carried out on the zone by a board, of which Dr H. R. Carter was chairman. Among their conclusions, they “found from the histories that malaria may prove a predisposing factor, as histories of continued fever for several days preceding the onset of the pneumonia were common.”70

Dr Deeks states further on, in an analysis of 574 cases which were under his care:71

The most striking factor in the above analysis, however, is the small number of cases complicated by malaria, only sixteen cases being recorded in which the organism was present. This observation has been repeatedly verified since, and it may be said in general terms that malaria organisms and leukocytosis are incompatible conditions in the human organism. Leukocytosis takes care of malaria, and in the treatment of pneumonia even the presence of organisms need not be considered in the general management of the case.

On the other hand, it may be noted here that leukopenia, which is present in typhoid fever, is not incompatible with malaria, and here these two affections are found almost constantly to exist, and necessitate the administration of quinine through the whole or a great part of the course of the former.

These observations are of great interest from many points of view. We know that, although blackwater fever is due to malaria parasites, these disappear very rapidly from the blood when the actual attack of blackwater comes on. It would almost appear as if something similar occurred when pneumonia sets in, and that the increased number of leukocyte called out to deal with the pneumonia germs incidentally destroy the malaria parasites. In this way evidence would be lost of the part which malaria played in predisposing the patient to pneumonia. In the Federated Malay States I have seen only two outbreaks of pneumonia on estates; and both estates were malarious. Of course, isolated cases of pneumonia are frequent; the outbreaks I refer to were epidemic in character.

On the Rand, in South Africa, which is a non-malarious elevated region, the negro races show a similar liability to pneumonia. It has been shown that a high percentage of the labourers harbour malaria parasites; that the disease occurs chiefly among the new arrivals; and that there is, if not overcrowding in the labourers’ quarters, certainly no special allowance of floor and air space. Under these circumstances, where malaria can only be the result of an infection before arrival, it is not impossible that the change to the cold climate lowers the resistance of the labourer to his malaria parasites, and also to the pneumonia germs. It would be interesting to learn what percentage of the pneumonia patients on the Rand show evidence of malaria infection at the time of the pneumonia attack, or immediately before it. As the high mortality in the mines has received and is receiving the most careful consideration, it is to be hoped this point will be investigated, if already it has not received attention.

| 15.6 |

Yellow fever extinguished |

It is now so long since yellow fever was stamped out on the zone, that people have almost forgotten this brilliant achievement. When he went to the zone, Colonel Gorgas was confident he could eliminate it72 “by the same methods that were so successfully adopted in Havana;” and he has justified that confidence, for the zone has been free from the disease since 1906. The public water supplies were opened on the 4th July 1905, and from Table 15.6, which is taken from Mr Bishop’s book,73 it will be seen how quickly after that yellow fever disappeared, to which happy event the strenuous exertions of the Sanitary Department in abolishing rainwater barrels and other breeding places of the Stegomyia as rapidly as possible materially contributed.

| Total | Employees | Place of origin | |||||||

| Year | Month | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Panama | Colon | Canal zone | Foreign ports |

| 1904 | July | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | – | – |

| Aug. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Sept. | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | |

| Oct. | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Nov. | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Dec. | 6 | 1 | 2 | – | 5 | 1 | – | – | |

| 1905 | Jan. | 19 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Feb. | 14 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 10 | – | 2 | 2 | |

| March | 11 | 3 | 6 | – | 7 | 4 | – | – | |

| April | 9 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 1 | – | – | |

| May | 33 | 7 | 22 | 3 | 16 | 14 | 3 | 1 | |

| June | 62 | 19 | 34 | 6 | 29 | 17 | 13 | 3 | |

| July | 42 | 13 | 27 | 10 | 15 | 9 | 8 | 10 | |

| Aug. | 27 | 9 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 1 | |

| Sept. | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Oct. | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | – | – | |

| Nov. | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | – | |

| Dec. | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | |

| 15.7 |

Malaria |

It was about malaria that Colonel Gorgas had most anxiety. In Havana he had organized a scheme of mosquito destruction which, “though entirely directed against yellow fever, was almost equally successful against malaria.” He felt confident that he could eliminate yellow fever from Panama; “but malaria, in my opinion, is the disease on which the success of our sanitary measures at Panama will depend. If we can control malaria, I feel very little anxiety about other diseases. If we do not control malaria our mortality is going to be very heavy.”74

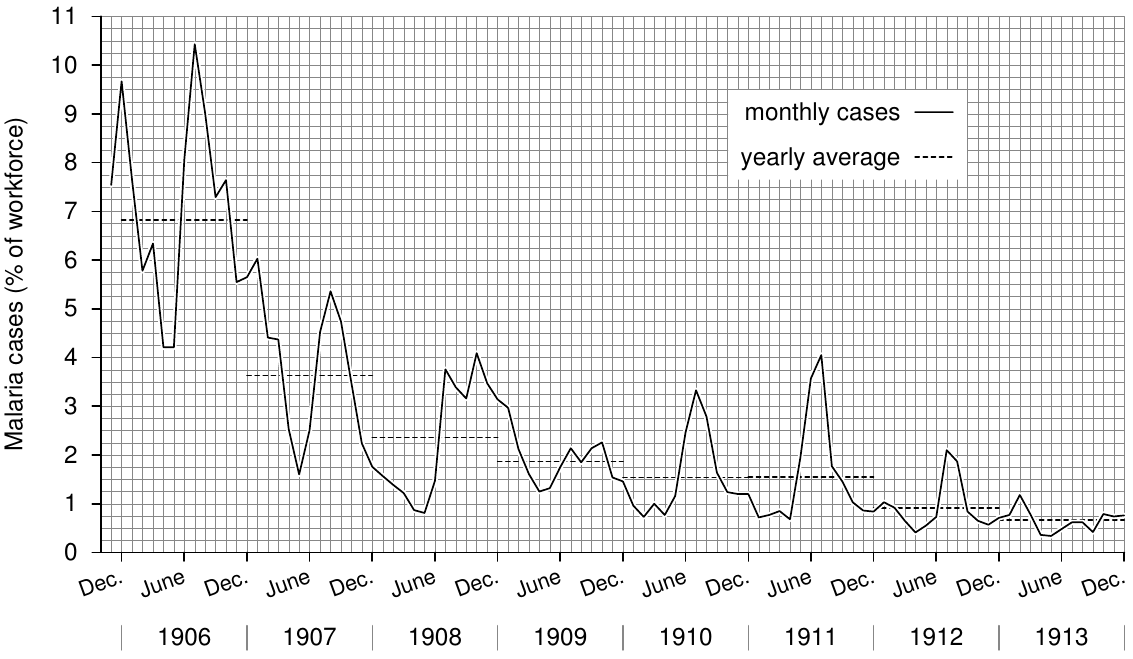

How wonderfully he has controlled malaria will be seen from the chart in Figure 15.1. Year by year the amount of malaria has diminished, until in 1913 no trace of the seasonal rise during wet weather can be seen.

Table 15.7 shows the actual number of cases of malaria admitted to hospital, the labour force, and the admission rate per 1000 of labour force. If malaria has not been completely stamped out, it has been reduced to less than a tenth of what it was. In 1913, among the white employees from the United States, there was only one death from malaria and one from blackwater fever. I have not got the figures for 1913 relating to deportations from the zone for illness, but no white employee from the United States was invalided from the zone on account of malaria during the years 1910, 1911, or 1912. Indeed, for the year 1912, only fifteen United States employees were invalided from all causes, including injuries.

I have already emphasised the fact that most of the negroes do not live in screened houses, and that many live in “shacks” on the edge of or in the jungle. A few, only those who live in houses with a water supply and water closet, comply with any sanitary regulations, but none conform to any regulation for the control of malaria. None are under any restriction as to where they go or when. The same freedom of movement applies to both Americans and Europeans; and the greater incidence of malaria among the Europeans can be attributed to their carelessness in frequenting negro quarters at night, and their general disregard of all sanitary precautions against malaria. It is perfectly true that malaria has not been completely abolished; but it must not be forgotten first, that many negroes live in huts close to and in the jungle (in 1913 they were being rapidly removed for military reasons); and secondly, that many thousands of blacks already infected with malaria arrive from the islands. These people suffer from relapses after their arrival, which swell the hospital returns; and the absence in 1913 of the seasonal rise in the malaria curve shows conclusively that most of the existing malaria is now the result of relapses.

| Year | No. of cases | Labour force | Admission rate per 1000 |

| 1906 | 21,739 | 26,705 | 821 |

| 1907 | 16,753 | 39,343 | 424 |

| 1908 | 12,372 | 43,890 | 282 |

| 1909 | 10,169 | 47,167 | 215 |

| 1910 | 9,487 | 50,802 | 187 |

| 1911 | 8,987 | 48,876 | 184 |

| 1912 | 5,623 | 50,893 | 110 |

| 1913 | 4,284 | 56,654 | 76 |

Nor should it be forgotten that the Sanitary Department has had to work under many disadvantages. The chief difficulty has been that the sanitarian could not adopt the best method of eliminating the disease, namely, drainage. Drainage systems have had to be destroyed by the engineers time after time, so that they might dispose of the spoil from the Cut. This constant interference with drainage led to the continual creation of new swamps, which had to be controlled by oiling. Indeed, engineering work of all kinds has so frequently changed the minor as well as the major features of the topography of the zone, that the sanitary and divisional inspectors have had to be forever on the watch for new breeding places. In an ordinary town or village, one who is in the habit of searching for mosquito larvae knows exactly where all the breeding places are; nor does he find them to vary even over a period of many years. This reduces the amount of supervision very greatly, but in Panama it is not so.

Again, in Panama many places were occupied only for a short time, and it was not advisable to carry out any permanent drainage. Places like Juan Grande, Mamei, and Old Frijoles were under the lake in 1913; and several other places have since disappeared under its waters. Where only temporary occupation was contemplated, only temporary measures of control were adopted; and such measures are less certain than drainage. Perhaps one of the greatest disadvantages under which the Government has worked has been the artificial condition of the whole zone. The Americans are building a great highway for commerce and war, and for the latter object defence from the attack of any enemy is imperative. It was to give security from bombardment by a hostile fleet that the locks were built about seven miles in from the ocean. As a safeguard against the land operations of an enemy the whole zone, except at a few stations, is being allowed to revert to jungle; indeed it has been depopulated, so that it must revert to jungle. Now we have seen that in the Federated Malay States, and as we shall see later in British Guiana also, the development of agriculture is the most effectual way of eliminating malaria under certain conditions. In Panama they have not had any assistance whatever from agriculture.

Before concluding I would make two more observations. The first is that although malaria had been controlled in places like Ismailia and Klang before the Americans went to Panama, the reports from these places would have been of comparatively little value to a sanitarian working under the peculiar conditions that exist in the Isthmus, if, indeed, they would not have been actually misleading. It may be said, therefore, that practically the whole of the anti-malaria work in Panama is original; as such it was at first largely experimental, and we can trace, I think, certain modifications in the original plan in later years.

Need I emphasise how difficult his task is when the sanitarian has not only to carry out a scheme of sanitation, but has also to invent it?

Secondly, I would point out that during the whole period under review, thousands of people, many of whom were highly susceptible to malaria, have poured into the zone each year; and this is, almost more than anything else, the circumstance which produces the severest outbursts of malaria. In conclusion, we can say that with almost everything against it, and tested by this the severest test, the Department of Sanitation comes out triumphant.

| 15.8 |

Malaria in small stations and camps |

I have already said that many stations were small or were only occupied temporarily, and it is among these that we see how quickly the Department brought malaria under control. For Toro Point I have already given figures which illustrate this (see Table 10.2). Major Noble has kindly supplied me with the figures relating to several other places.75

| 15.8.1 |

Juan Grande Camp |

This was in Gorgona district, and was occupied temporarily by Spaniards. It is now under the lake. The anti-malarial measures consisted of a little draining, but mainly screening, oiling, and bush clearing close to the camp. Table 20.1 shows the percentage of the labour force sent to hospital for malaria each week.

| 15.8.2 |

Mamei Camp |

This also was in the Gorgona district, and is also now under the lake. No less striking have the results been here (see Table 20.2).

| 15.8.3 |

Empire |

Here there is now a permanent drainage system and comparatively little oiling is required. But in 1907 drainage was less advanced and there was a good deal of malaria. The contrast between 1907 and 1912 is indeed wonderful (see Table 20.4).

| 15.9 |

Mosquito catching and screening |

The protection obtained from screening ordinary railway trucks and catching each morning all mosquitoes that have gained an entrance, is undoubtedly most valuable, and the highest credit must be given to the Sanitary Department for evolving a method which could be put into practice in many places where nothing else could possibly have saved a construction force from practical annihilation. In a conversation Colonel Goethals told me that some of the worst cases of malaria on the Isthmus had occurred among the members of the party who were out in the jungle camps surveying the watershed of the Chagres River and what were to be the limits of the future Gatun Lake. “Chagres fever” or “jungle fever” was always specially dreaded for its severity, the reason for this being of course that in such jungle very large numbers of Anopheles occur, and the inhabitants of small camps, some of whom are sure to bring malaria with them, are constantly being reinfected, so that no sooner have they overcome one set of malarial invaders than they have to meet another.

Mr Le Prince gives an illustration of the value of these methods of protection in Ross’ Prevention of Malaria, and Dr Orenstein gives other illustrations;76 but I need not reproduce these here, after having given such striking examples as Juan Grande and Mamei.

Mosquito catching without screening, is, I believe, also of great value; but I have no figures in support of this. An opportunity of seeing the value of mosquito catching alone on a large scale was to occur at the end of 1913, when some of the troops were to go into camp; but so far I have not seen the actual figures.

| 15.10 |

Other Diseases |

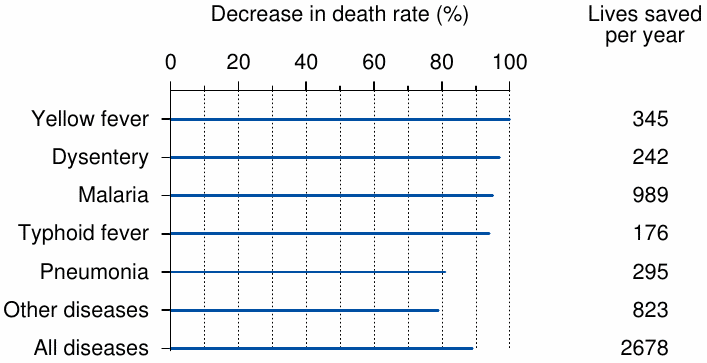

Dysentery, typhoid, and all other diseases have been reduced in a way just less striking than yellow fever. To illustrate the saving of life from all diseases the Sanitary Department prepared in 1910 an interesting table called “The Isthmian Canal Commission, in account with the preventable diseases.” It shows the changes in death rate due to infectious diseases that are amenable to sanitary prevention, between 1884, the year in which the French workforce was at maximum strength, and 1909, the peak year of the American workforce (see Figure 15.2).

Since then the amount to the credit77 of the Department has steadily increased, and the total of lives saved to the end of 1913 amounts to practically 30,000.

| 15.11 |

Deportations |

| Category | Year | |||||

| 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | |

| Black | 110 | 66 | 97 | 81 | 87 | 107 |

| White | 175 | 80 | 117 | 86 | 67 | 79 |

| Male | 175 | 143 | 212 | 157 | 146 | 171 |

| Female | 0 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Employees | 152 | 133 | 197 | 143 | 137 | 161 |

| Non-employees | 23 | 13 | 17 | 24 | 17 | 16 |

| Malaria | 55 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Tubercle | 15 | 56 | 95 | 63 | 60 | 40 |

| Insane | 14 | 15 | 8 | 28 | 33 | 19 |

| Dysentery | 8 | 8 | – | – | – | – |

| Alcohol | 5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Injury | 13 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 26 | 60 |

| Beri-Beri | 9 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nephritis | 4 | 11 | 33 | 12 | 4 | 11 |

| Rheumatism | 6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Heart etc. | 6 | 14 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 10 |

| Nervous system | 5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Miscellaneous | 35 | 27 | 42 | 42 | 36 | 33 |

It has been said that the low death rates are the result of the Department shipping to the United States or to their homes all those who are likely to die. Of all tropical countries, it is probably true that immigrants do seek to return to their original homes when ill (it is one of our original animal instincts); but in the case of Panama it will be seen from the following tables that deportation plays practically no part in lowering the death rate of the very large population from whom the deportees are drawn. Even if every person deported had died on the zone, it would have had very little effect on the statistics; while, as a matter of fact, many, such as the insane, would probably recover, whether sent home or allowed to remain on the zone; and although some of the injured might not be able to earn a living, few would probably die since they had recovered sufficiently to be moved. Major Noble was good enough to furnish me with full details of the deportations from the year 1906 to 1912. It does not seem necessary to give them in full, so I will condense them all except that for the year 1912.

It seems to me that these tables dispose of the statement that the low death rate is artificial. I have reproduced them, however, because there is no doubt of the bona fides of those who made the statement; I have heard it in the United States, in Europe, and in Asia.

| 15.12 |

Immigrants Rejected |

Each year the number refused landing is published. In 1913 the total number refused admission at Colon-Cristobal and Panama-Ancon—that is, at the two ends of the Canal — was only 59 out of a total of 87,961 passengers inspected. Disease of the eyes, trachoma, is the chief cause of rejection, so it is obvious that rejection of immigrants does not play any real part in lowering the death rate, as has also been suggested.

| 15.13 |

The Number of Employees |

It has been suggested that the number of employees upon which the statistics are based, is incorrect; that the population is not so great as the figures; and that consequently the death rate is higher than is given. At the bottom of this suggestion there is the microscopic particle of truth upon which most false statements are founded. On the zone it is, of course, impossible to take a monthly census of the people; and for statistical purposes the number on the payrolls is taken as the monthly population. That a certain number of the men stop work, go to another part of the Canal, represent themselves as new arrivals, and re-enrol, is of course possible; but there is not the slightest reason to suppose that the number who do this can possibly invalidate the statistics.

The fact seems to be that the success of the sanitary work on the Canal has been so far beyond men’s dreams of what could be done, that they deliberately refuse to believe it, and raise the most absurd arguments in support of their disbelief. The modern man is distinctly sceptical of fairy tales and miracles, whether ancient or modern; and he places the mosquito theory among the fairy tales. So when the modern knight dons his wire-gauze armour, leaps jauntily over an open drain, couches his tile-pipe in its rest, tilts at and slays the mighty midge, to free, not one fair maiden, but a whole dusky race, the modern onlooker is provoked first to amusement and then to scepticism. Finally, he may learn the mosquito may be, after all, mightier than the dragon, and a vast deal more real; but many are still in the sceptical and puzzled stage, and the laugh really is on the side of the knight as he watches the modern man try to explain away the modern dragon and the modern miracle.

Yet my experience of the men of the Sanitary Department was that they recognized in the frankest way not only how far they had been successful, but also in what way they had fallen short of success. Not only was there no attempt to conceal anything, but my attention was drawn time and again to what could be improved, and where they had failed. Indeed the great charm about my visit to the zone, was the frankness of every member of the Sanitary Department whom I met.