| 5 |

Malaria in India |

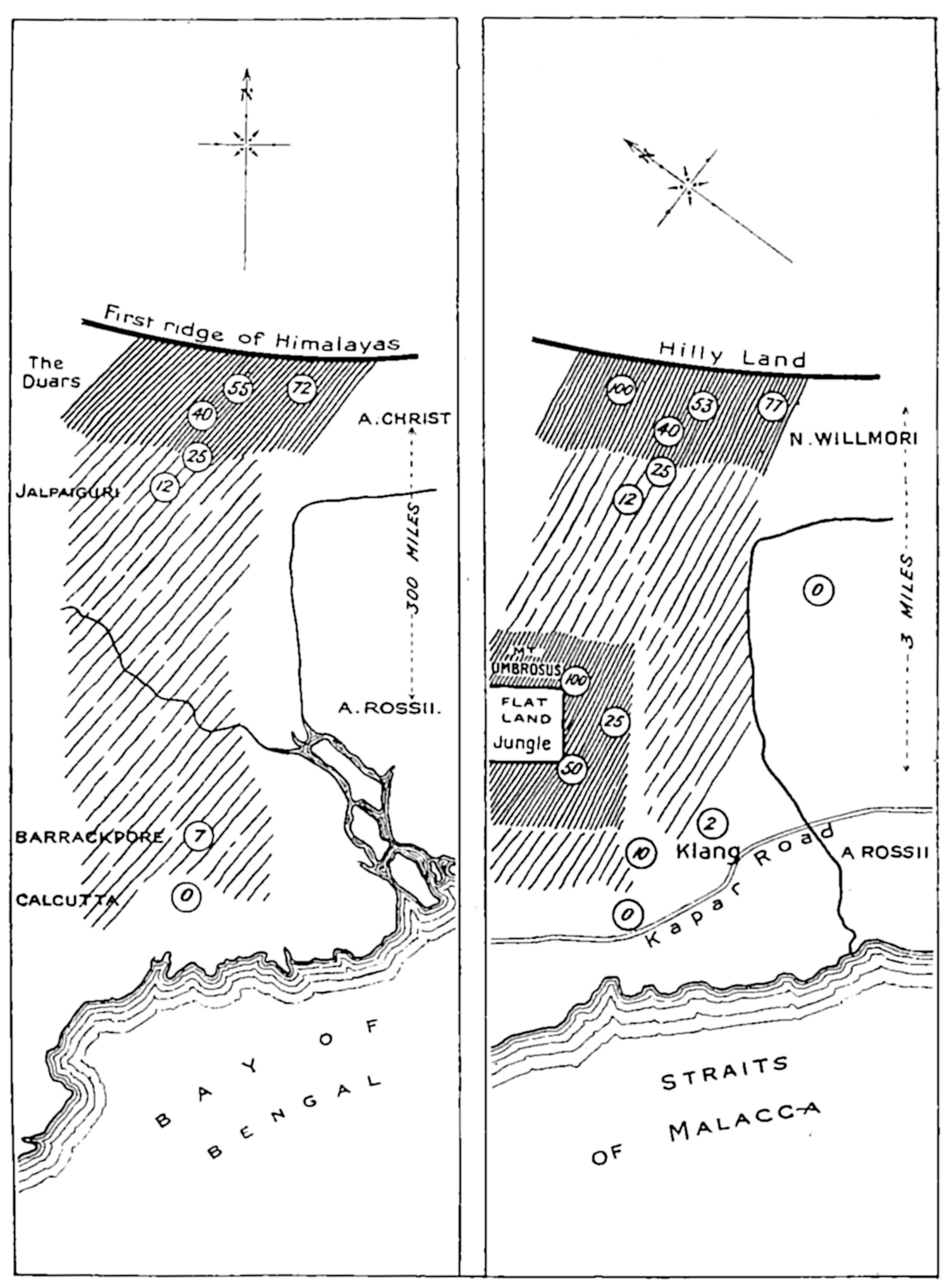

While the contrast between Malaya and Italy was very marked, no less striking was the parallel noticeable between my observations in Malaya and those recorded in the admirable reports of the Commissioners to the Royal Society published in 1902, and by later observers elsewhere. From these it was evident that intense malaria was often found in the hills, while the plains were not necessarily malarious, as the following extracts will show.

In 1909, in a letter to the Lancet, Major S. P. James and Captain Christopher write:

We are aware that India as a whole is not intensely malarious. There are wide tracts of country where the disease though present is not markedly interfering with the prosperity and natural increase of the population. In such areas action for the reduction of the prevalence of malaria is unnecessary; the disease is sufficiently dealt with by general arrangements, such as are taken for the mitigation of other diseases. Secondly, there are areas where malaria is constantly present to a moderately intense degree; and, thirdly, there are areas in which the disease can only be described as decimating the people, and converting once populous and prosperous districts into scantily peopled and decayed ones.

In the sixth report of the Commissioners of the Malaria Committee of the Royal Society, published in 1902, a map will be found showing the malaria index of Bengal. The report says:

The following map and table will at once show how in proceeding from Calcutta northwards till the foot of the Himalayas was reached—a distance of some 300 miles—we passed from a region the endemic index of which was 0.0 percent, through regions with increase in indices of endemicity, till at the foot of the hills, in a district known as the Duars, a very high degree of infection was reached, 40 percent to 72 percent, as high indeed as that found by us in West Africa. We have, then, in a region not above 300 miles in latitude, subject to almost identical climatic influences, an endemic index varying from 0.0 percent to 72 percent.

Commenting on this, I wrote:12

If we take a map of the Klang district from the sea to the hills we find that malaria may be represented on, say, an estate on the Kapar Road by a spleen index of nil; passing inwards we find perhaps an increased index due to proximity to jungle. Once, however, we reach the first of the hills, even of the small hills, of the Peninsula the spleen rate rises to from 70 to 100, and the most intense malaria is met with, due to an Anopheline which breeds in hill streams. The distance from the place with the spleen rate nil to that with a spleen rate of 100 is about 3 miles. The climate of the two places is the same.

It is impossible to look at these two maps without the idea at once springing to the mind that the similarity is more than a coincidence. We find that the malaria in both is highest when we reach the hills, and that the carrier of malaria in the hill land of both is an Anopheline which breeds in the hill streams.

In both, when we reach the plains another Anopheline is the carrier. Malaria is much less intense, and may even be entirely absent. Is it too much to believe that our observations in the Malay Peninsula give the key to the malaria of India?

In the Malay Peninsula in the short span of one generation the country has been reclaimed in considerable areas from absolute jungle.

We see that when first inhabited the plains or flat land are no less unhealthy than the hills, but when the land has been drained and cultivated it becomes much less malarious. We can actually see the process going on under our eyes in Malaya.

I suggest that the map and our knowledge of Indian malaria indicates that what is occurring here now occurred in India in the past. Only in India everything has been on a more extensive scale. In Malaya the space is 3 miles, and the time one generation; while in India the space is 300 miles, and the time perhaps 300 generations. History does not tell us when first the Indian plains were cultivated.

And, if this be so, is it too much to believe that what freed the greater part of the plains from malaria will free the remainder; that the small foci remaining on the plains will yield at once to properly devised and probably inexpensive operations, which at the same time will appreciate he value of the land?

Referring to the areas of intense malaria where the population is decimated, the [Indian] writers continued:

It is upon such areas as the last—where malaria is present in intensified and epidemic form, and is acting as a pestilence—that attention should first be concentrated. Such epidemics have causes which can be traced, and even at present it is known that the factor of Anopheles mosquitoes is only one of many that are concerned in bringing about the epidemic result. In the great industrial centres, for example, we have malarial epidemics whose immediate cause is the immigration under special conditions of non-immune people from healthy districts to foci of malaria started by this very process of immigration. We need not here describe the events and conditions that are concerned in causing epidemics of malaria in such centres, nor need we mention other examples in which recent work has revealed what are the really important factors concerned. It suffices if we emphasise the fact that the prevalence of Anopheles, though always important, is by no means in every case the most important factor to be considered.

The great industrial centres to which the writers allude are the tea plantations of Assam, etc., and we find their parallel in Malaya in the rubber estates of the hilly land. In both there is “the immigration under special conditions of non-immune people to foci of malaria.” In both there is the most intense malaria.

The Indian writers had been greatly impressed, and very properly impressed, with the severity of the outbreaks which follow the introduction of non-immune people to areas where malaria-carrying Anopheles exist. In an able paper13 they had shown how the coolie camps of the great engineering works had ever been foci of terrible epidemics, or, as they called it, a hyper-epidemic of the disease. Of the importance of this factor in the production of epidemics, I have already written, and am in accord. But having had the good fortune to witness similar immigration to estates, and to public works where the Anopheline factor was absent, and having noticed the absence of the outbreaks when the mosquito was absent, I suggested the Anopheline as the more important factor, as follows:

But in Malaya the same immigration of the very same people (indeed, where coolies are transferred from one estate to another, of the very identical individuals), occurs to flat land and hilly land estates equally; but it is only on the hilly places that malaria occurs, while on the flat land estates where the coolies are housed half a mile from jungle, malaria is practically unknown, and the spleen rate is nil. If these be facts in Malaya, I would suggest that the Anopheline is the important factor in the areas of intense malaria in India, as I consider it is in Malaya.

The parallel which I suggested in 1909 was, however, to be closer than I suspected, both in respect to the plains and the hills.

In preparing the map of Klang for comparison with that of Bengal, I had added an inset on the plains, and called it “Flat Land Jungle." Referring to this, the editor of Paludism14 pointed out that Stewart and Proctor had demonstrated that in villages near to jungle in Lower Bengal the spleen rate was high, just as in Malaya, and that the inset marked by me “Flat Land Jungle” in the map of Malaya might be inserted in the Indian map, so making the parallel I had suggested complete in every respect. In his opening address15 the Hon. Surgeon-General Sir Pardey Lukis, Director-General, Indian Medical Service, said:

All the schemes I have mentioned so far are for urban districts only, but you must not imagine that the very important question of malaria in rural areas has been neglected; on the contrary it has our most earnest attention, and in this connection I must allude to the excellent work done by Stewart and Proctor in Lower Bengal. They have shown that a close connection exists between over-vegetation and intensity of malaria—in which respect they are in close agreement with the findings of Watson of Malaya. At the suggestion of the Government of India, the Government of Bengal has taken up the matter, and it is proposed to allot a considerable sum of money to carrying out an extensive experiment of jungle clearing in the neighbourhood of inhabited areas. Should this experiment prove a success, we shall have at our disposal one method at least of improving the conditions obtaining in small villages, especially in the deltaic area. But although his method is likely to be useful in flat country, it is doubtful whether it will avail in hilly tracts, especially in hilly tracts intersected by ravines. Watson has found it useless in Malaya, and Kendrick has arrived at similar conclusions in the Central Provinces. Major Perry, too, in his paper which is for discussion today, goes carefully into the practical question of jungle clearing in the hilly tracts of the Presidency, and shows that whereas on the 3000 feet plateau jungle clearing produces little obvious effect, on the 2000 feet plateau the conditions are different, and the proper clearing of jungle gives hope of the practical eradication of malaria.

| 5.1 |

The Identification of Anopheles maculatus |

Turning now to the parallel of the hills again, we find it closer than was originally suspected. In Malaya we had identified the stream-breeding Anopheles as A. willmori. A. maculatus had been recorded by Mr Theobald as among the specimens sent to the British Museum from the Federated Malay States, but neither Dr Leicester nor I had ever caught a specimen. In his monograph on The Culicidae of Malaya, Dr Leicester states, when writing of A. willmori:

This mosquito evidently bears a strong resemblance to A. maculatus, specimens of which have been taken in Taiping. It differs, however, in the banding of the palpi. A drawing of the palpi of maculatus is given in Theobald’s monograph, and shows three white bands at the apex instead of two equal bands present in willmori.

With not only a written description, but with a drawing before us, demonstrating the difference between Theobald’s maculatus and our Malay species, we were satisfied that the mosquito with which we had to deal was not A. maculatus but A. willmori. When making a visit to Japan in 1911, I was therefore much interested to see what Anopheles was responsible for the malaria in Hong Kong. The three species there had been identified as A. rossii, A. sinensis, and A. maculatus as far back as 1901, by Major James, when passing through Hong Kong with troops sent from India to the Boxer Rising.

In the collection at Hong Kong there were two specimens labelled A. maculatus, and on examination I recognised them as identical with what we called A. willmori. But, as I pointed out, they differed from Theobald’s description of A. maculatus in having three palpal bands and not four.

The next step in the discovery of the real identity of the mosquito took place when in 1911 Major S. P. James visited the Federated Malay States when conducting his inquiry on behalf of the Indian Government on the distribution of Stegomyia fasciata (Aedes calopus), and the probability of yellow fever reaching Asia after the opening of the Panama Canal. Major James had fortunately brought with him a fine collection of Indian mosquitoes, and he showed that our A. willmori was identical with the Indian A. maculatus; that A. maculatus had only three palpal bands, not four as described by Theobald; and he suggested that since specimens of A. maculatus had occasionally four bands, Theobald might have got one of these for his type specimen.

Finally, when Dr A. T. Stanton was in England, the specimens in the British Museum were re-examined and he writes:

The nomenclature of this and closely allied species has given rise to more difficulties than any other Oriental Anopheles. An examination of the types of Anopheles maculatus, Theobald, has revealed a reason for the confusion that has existed in the minds of Eastern workers as to the characters of these species. The types are not male and female of the same species, but represent two distinct species, the male being known to Eastern workers as maculatus and the female of the species known to them as karwari.

In view of the profound economic importance of the insect which lives in the hill streams of Malaya, it was of great importance to other countries to have its identity properly established. Its presence or absence in other countries could be definitely ascertained, and measures found useful in Malaya could be adopted if necessary.

| 5.2 |

The Duars |

Early in 1913, in re-reading series No. VII. of the Reports of the Malaria Commissioners to the Royal Society, I observed the small footnote on p. 37: “In Report VI. A. metaboles was throughout erroneously printed for A. maculatus.” A. maculatus by this time proved to be identical with our A. willmori in the Federated Malay States, and had a new interest for me, and turning back to Report VI. I found it referred to a mosquito found in the Duars. “The district known as the Duars is a strip of land extending for some hundreds of miles along the foot of the Himalayas. It is a gently sloping tract of from 800 ft. to 1200 ft. above the sea, and abounding in small streams.”

In the Duars the Commissioners found three Anopheles, namely: A. rossii, A. christophersi, and A. maculatus. From experiments, and from the fact that the spleen rate in Calcutta was 0, although A. rossii abounded, they concluded it was not a carrier of malaria.

Of A. christophersi, however, they say (p. 10): “This species is undoubtedly a good carrier. Sporozoites were found in four out of sixty-four specimens, or 6.25 percent. … A. metaboles [A. maculatus].—From the difficulty of obtaining the adult insects, sufficient numbers were not examined to determine whether this species carried malaria. Eleven specimens from huts were negative" (p. 10).” – “A. metaboles [A. maculatus] was in the Duars also a very common mosquito, judging by the large numbers and wide distribution of larvae” (p. 8).

Referring to their breeding place, the report says (p. 19): “A. christophersi: in the Duars this species breeds in sluggish streams with grassy edges. It was never found by us in puddles in the coolie lines, or in small ponds, roads, paths, etc. In some cases larvae were dipped up from water running with considerable velocity, but always among the grass at the edge.” Of A. metaboles: “The larvae of this species also occur in streams more or less rapid. They are also abundant in swampy tracts by the side of streams, in rice fields, and small pools. They are not found in the small foul pools in the coolie lines. They occur at a height of 5000 ft. This species has been found by us at very considerable distances from habitations.”

It will be seen from these extracts that A. metaboles (maculatus) in the Duars was found in much the same situations as it is found in the Federated Malay States, that is, in small streams in the hills. Although not actually convicted of carrying malaria in India, there is little doubt that this was simply due to the difficulty the Commissioners had in catching adult insects.

There is some evidence, however, in the report to show the possibility of A. maculatus being even more important than A. christophersi. “At Sam Sing (3000 ft.), Bengal Duars, this species A. metaboles (maculatus), was found alone and associated with an endemic index of 25.”16 It appears, too, that “A. christophersi was only found by us in the Duars district, and it was not found above a height of about 1000 feet.”17 A. metaboles, on the contrary, had a wider range, and “occurred in small numbers as one approached the foot of the hills. It was the commonest Anopheles in the upper portion of the Duars and lower hills. It occurred also at an elevation of nearly 5000 feet near Kurseong."18

| 5.3 |

Jeypore Agency, Madras |

Subsequently the Commissioners went to the Jeypore district, and were at once struck by the fact that “the Anopheles fauna of the Duars and the Jeypore hills, two regions of intense endemicity, is almost identical.”19 And just as on passing from the swampy plains of Bengal to the Duars, they had passed from regions of low to regions of high spleen rates, and had been struck by the contrast, they note in Jeypore Agency, Madras “a striking contrast which occurred between the high endemic index of the hill regions and the low index of the adjacent plain district.”20

They record that A. maculatus is not found on the plains of Bengal, and that since leaving the Duars they had not encountered it, until they reached the Jeypore hills.21 In view of our experience in the Federated Malay States of the importance of this mosquito, it is significant to find among their conclusions “that in the two regions of intense malaria visited by us (Duars and Jeypore hills), black water fever is well known and has attacked a large proportion of the resident Europeans.”22

I do not wish to press unduly the importance of A. maculatus as against A. christophersi; for one stream-breeder would be as bad as another, provided both were equally common and were equally suitable for the sexual stage of the parasite’s life. It does not, however, appear to me from reading the reports that the two mosquitoes are quite alike. A. christophersi appears to live only under an elevation of 1000 feet, and although found in running water, the larvae “were always amongst the grass at the edges.” In Malaya A. albirostris and A. karwari live in grassy streams, and thus show a resemblance to A. christophersi, but are certainly not so important as A. maculatus. A. maculatus has a wider range of elevation than A. christophersi in India, and our experience in the Federated Malay States suggests that it may not be confined only to grassy streams. The point is worth further investigation. I may be quite wrong in my suggestion. I would, however, emphasise that A. maculatus does exist in hill streams in India, and that measures inimical to A. maculatus would be equally inimical to A. christophersi and A. jeyporensis.

| 5.4 |

Ckota Nagpur |

Finally, before leaving the subject of malaria in India, I would draw attention to some points in Major Fry’s First Report on Malaria in Bengal. Unfortunately he was unable to identify the carrier of malaria either in the plains of Bengal or in Chota Nagpur. But in the latter division he gives a table showing the distribution of malaria in passing from the plains up to the plateau and then to the higher ranges. He describes these regions as follows:

- (1)The more or less flat plains of Manbhum, with a porous soil, and hot, dry climate. Rice, however, is grown, and the “crop entirely depends on rainfall, which is collected and drained off from the higher levels to a series of terraced rice fields which spread fanwise down the slopes until finally the water is allowed to flow into rivers.” As will be seen from Table 5.1, the spleen rate is very low.

- (2)The “Terai” region, situated at the foot of the slopes from the plateau to the plains. In travelling here, “at frequent intervals one crosses small rocky hill streams which are leading down to the plains.” Again, as in similar places in Malaya, there is intense malaria.

- (3)The third region is the plateau itself, which covers the greater part of Chota Nagpur. This plateau has a general elevation of some 2000 feet. Here is but little malaria; while when we pass to

- (4)The villages at the foot of the Ghats to the north, the malaria rate again rises.

| Region sampled | Number of children examined | Spleen rate | |

| I | Seven villages of the plains | 137 | 1.6 |

| II | Seven villages at the foot of the Ghats | 109 | 88.4 |

| III | Fifteen villages on the plateau (elevation 2000 feet) | 528 | 7.0 |

| IV | Four villages on Northern Ghats | 78 | 37 |

Table 5.1 condenses the data reported by Major Fry. Unfortunately Major Fry was unable to complete his investigation, but it is impossible to resist the conclusion that, as in the Duars, in Jeypore, and in Malaya, a stream-breeding Anopheles is responsible for the intensity of malaria in the hill regions of Chota Nagpur. Indeed Major Fry himself suggests (p. 29) that observers visiting at a time when the floods were over would find “in these hill streams a series of pools swarming with larvae.”

| 5.5 |

Ceylon |

A. willmori had been reported from Ceylon, and thinking that the observers there had possibly been misled by Mr Theobald’s description of A. maculatus, as we had been in the Federated Malay States, I asked Mr Edwards of the British Museum to re-examine the A. willmori in the collection of insects from Ceylon. This he was kind enough to do, and found, as I had suspected, the Ceylon insect to be in reality A. maculatus.

Ceylon is a country with a great mass of hills in it; but, as far as I am aware, no work has been published showing the relation of the distribution of the disease to the species of Anopheles.23

Probably the largest spleen census yet recorded has, however, been carried out in Ceylon, no less than 92,258 children having been examined. Of these, 34.05 percent had enlarged spleen, which shows that if any portions of Ceylon are healthy, others must be very unhealthy. I know from a friend that one estate at the foot of the hills suffers intensely from malaria, and I have heard that in some years malaria mounts to an altitude of 3000 ft. In view of what we have seen elsewhere, it is difficult to resist the suggestion that A. maculatus plays no unimportant part in the spread of malaria in Ceylon, and is probably the agent which causes it to rise to these heights in certain years.