| 7 |

Hong Kong and Philippine Islands |

| 7.1 |

Hong Kong |

Early in 1911 I had an opportunity of examining the Anopheles of Hong Kong. They had been identified first I think by Major James, when on the way with his regiment to the Boxer Rising; and this was confirmed afterwards by Mr Theobald. Three species of Anopheles have been found, namely, A. rossii, A. sinensis, and A. maculatus.

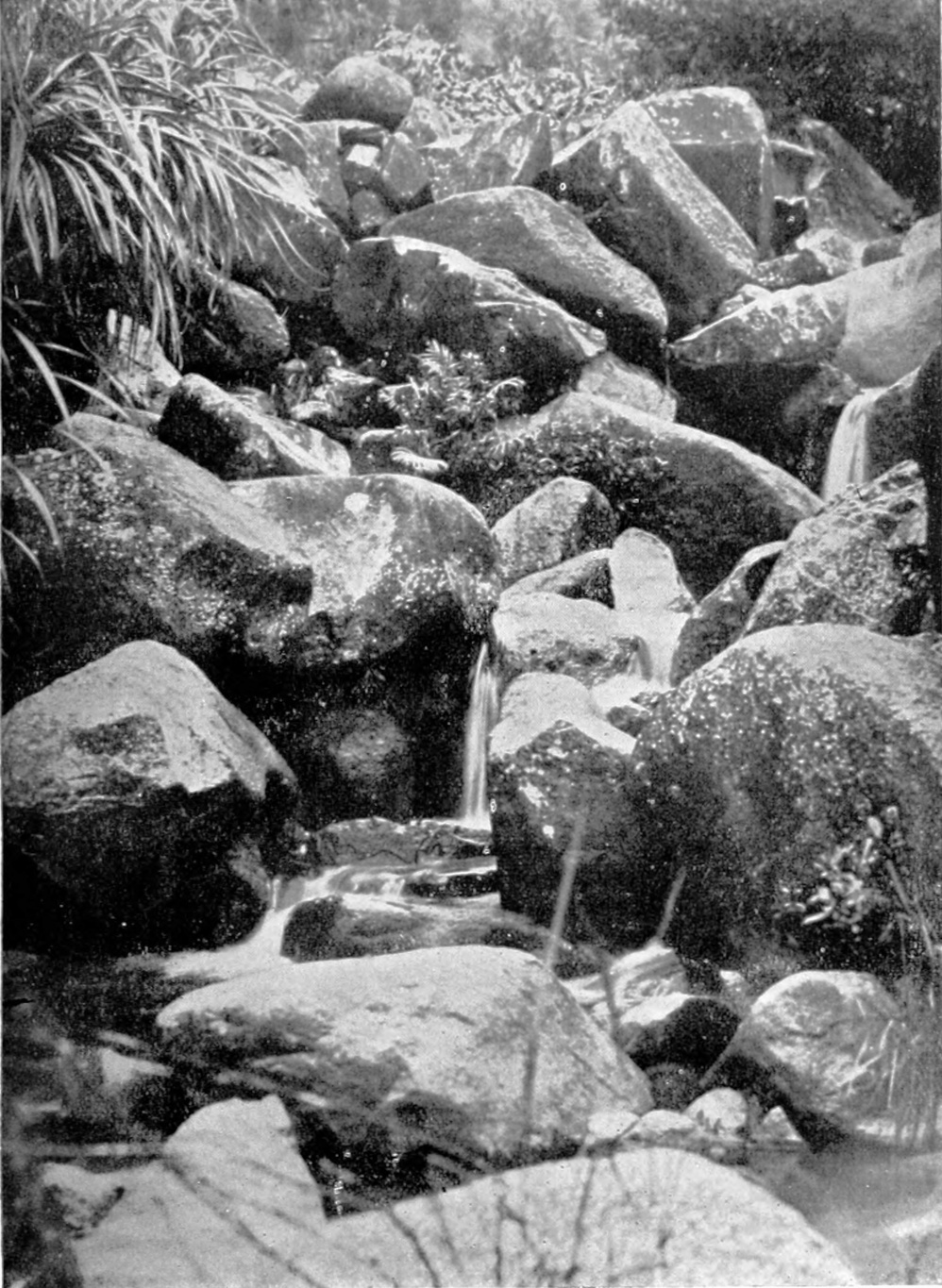

In the laboratory I found two specimens labelled A. maculatus; these I recognised at once as identical with our A. willmori, Leicester. For the reasons given before, I could not then accept the name maculatus; but maculatus is the true name. In Hong Kong, just as in other countries where this mosquito exists, malaria is intense, especially when many newcomers or non-immunes are concentrated. The popular explanation of this is that the outbreak is due to disturbance of the soil; and Hong Kong’s medical history as regards this is indeed notorious. The mosquito breeds in the steep hillside streams. Great improvements in health have been effected by “training the nullahs,” that is, by building smooth channels with granite blocks. The mosquitoes are not found to breed in channels which have a grade of from 20 percent to 50 percent, except in dry weather, when leaves accumulate and offer the larvae a hold. This danger is obviated by sweeping out the leaves in dry weather.

| 7.2 |

Anopheles and malaria in Formosa |

A day’s sail from Hong Kong is the island of Formosa. It lies between the 21st and 26th degrees of north latitude. Malaria has been reported from it, and in Ross’ Prevention of Malaria, Dr T. Takaki, chief of the Sanitary Bureau of the Government of Formosa, gives the following list of Anopheles:

- (1)A. sinensis, Weid;

- (2)A. listoni, Liston;

- (3)A. rossii, Giles;

- (4)Anopheles species (from Taito);

- (5)A. annulipes, Walk;

- (6)A. maculatus, Theobald;

- (7)A. fuliginosus, Giles; and

- (8)A. kochii, Dönitz.

He regards A. sinensis as carrying only benign tertian fever. It is the most prevalent mosquito. “Next comes A. listoni, a much smaller but extremely dangerous species.” In another place27 Kinoshita says of it:

Every epidemic of Malaria tropica depends on the increase and decrease of Anopheles listoni … This mosquito develops very abundantly between the months of April and October. The new infections of tropical malaria begin also about the end of April and reach the highest number between June and July. A. listoni is generally more abundant in mountain regions than on the coast, and the distribution of tropical malaria corresponds. Taihoku, where A. listoni does not occur, is, therefore, free from tropical malaria.

Takaki says that A. annulipes, A. maculatus, and A. fuliginosus “are met with in the mountainous district.” Further on he gives the record from Kosenpo, a village “lying in the southern mountainous district. … In April 1907, malaria prevailed terribly in this locality, especially among Japanese newcomers, so that 30 percent of the Japanese residents proved to be malaria patients.” The figures for 1906 which he gives have a strong similarity to what we have in the Federated Malay States. The result of quinine administered, according to Koch’s recommendation, was a marked improvement in health, but again, as in the Federated Malay States, by no means an eradication of the disease. And yet Takaki says, “the prophylaxis was strictly conducted under the care of police officials.” Table 7.1 gives a summary of his statistics.

It should be added that although the total population is larger in 1908, the proportion of newcomers was greater in 1906 than in 1908. The figures for 1908 show a most satisfactory improvement in health; but even then eight men out of every ten became infected in the short malarial season which exists in Formosa.

It may be that A. listoni is solely responsible for all this malaria, and that A. maculatus is harmless in Formosa. But since malaria, as severe as that in Formosa, is found wherever maculatus alone exists, it would be safer not to overlook the possibility of maculatus being at least as important, if not more important, than listoni. It would also be interesting to have the Formosa listoni re-examined; like that named funesta in the Philippines, it may be christophersi, for the difference between these mosquitoes seems to be slight.

| Year | Quinine | Population | Cases | % | Deaths | % |

| 1906 | − | 785.2 | 4,209 | 546 | 59 | 75.1 |

| 1908 | + | 1719.2 | 1,467 | 82 | 9 | 5.2 |

| 7.3 |

Anopheles species of the Philippine Islands |

Nothing like the Indian malarial surveys have, so far as I am aware, been made in the Philippine Islands. Indeed, but for the work of Dr C. S. Ludlow, we would have little information about the mosquitoes of the Islands. Dr Ludlow, however, voluntarily received and classified all mosquitoes sent to her from the various islands, and from time to time has published her observations. In 1908, as her thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the George Washington University, she wrote, and subsequently published, The Mosquitoes of the Philippine Islands—the Distribution of certain Species, and their Occurrence, in relation to the Incidence to certain Diseases; and in 1913 the War Department of the United States of America published an account of the Disease-bearing Mosquitoes of North and Central America, the West Indies, and the Philippine Islands, also by Dr Ludlow. Working as far back as 1901, when the little that had been published about mosquitoes was scattered about in the journals of different countries, and was often faulty and misleading, Dr Ludlow, like almost every other worker in new ground, described as new some species that had already been taken and described in other countries. But despite this her collection was a very valuable one, and her identifications were in all cases confirmed by Mr Theobald at the time.

In view, however, of the importance of this subject, I visited Dr Ludlow at Washington, D.C. She was good enough not only to allow me to examine her specimens, but she also gave me a collection which I handed over to the British Museum for renewed comparison with the type specimens. Mr Edwards has examined them, and in Table 7.2 I give what may be regarded as the most recent list of the Philippine mosquitoes.

| Name | Synonyms |

| A. formosus, n.s., Ludl. | |

| A. rossii | Myzomyia rossii |

| A. ludlowi | Myzomyia ludlowi, n.s., Ludl. |

| A. indefinita | Myzomyia indefinita, n.s., Ludl. |

| A. christophersi | M. funesta, Ludl. |

| A. tesselatus | Myzomyia thorntoni, Ludl.; A. deceptor, Don. |

| A. flavirostris, n.s., Ludl. | A. punctuatus, Theo. (closely resembles albirostris.—M.W.) |

| A. parangensis, n.s., Ludl. | |

| A. pallidus | Stethomyia pallida, Ludl. |

| A. sinensis | Myzorhynchus sinensis; M. vanus |

| A. barbirostris | Myzorhynchus barbirostris |

| A. pseudobarbirostris | Myzorhynchus pseudobarbirostris, n.s., Ludl. |

| A. fuliginosus | Nyssorhynchus fuliginosus; N. nivipes, Theo. |

| A. philippinensis | Nyssorhynchus philippinensis, Ludl. |

| A. kochii | Christophersia kochii, Chris. Halli. James; Cellia kochii, Theo.; Nyssorhynchus flavus, Ludl. |

With only two exceptions, the European, African, Asiatic, and New World species of Anopheles are distinct. The two exceptions were M. funesta (A. christophersi), which was reported from Africa and the Philippines, and A. umbrosus, reported from Africa and Malaya.

M. funesta is probably the most important malaria-carrying mosquito in West, Central, and East Africa, and great importance must have been attached to it, if it had been proved to exist in the Philippines. Dr Ludlow’s identification was confirmed at the time by Mr Theobald of the British Museum; but the re-examination of a specimen by Mr Edwards leads him to the conclusion that the mosquito is A. christophersi. The other exception is A. umbrosus, which was reported from Africa as A. strachanii. It is possible that these two are identical, but as the museum collection of the Malayan species is rather poor, further material is necessary before a final decision is arrived at.

Dr Ludlow says: “M. funesta appears constantly in malarial outbreaks, so constantly, in fact, that the appearance of one specimen in a collection is enough to lead to a suspicion that malaria is present, and even a small number of them is usually accompanied or immediately followed by new cases, the number depending on the prophylactic control of the station.” It was sent in, however, from only ten out of forty-two stations. From one station there is a report: “Parasites found in the blood of every man in the command.”

It seems impossible that A. maculatus, a mosquito not more difficult to detect than A. listoni, can exist, when we consider the great mass of material which passed through Dr Ludlow’s hands. It is possible, therefore, that the Philippines furnish an example of malaria as carried by A. listoni unaccompanied by A. maculatus,28 and although I have no positive information on this point, presumably A. listoni breeds in a stream in the Philippines, as it does in India. The elucidation of this matter will be of first importance in the prevention of malaria in the Islands.

Dr Ludlow also points out the association of M. (A.) ludlowi with malaria. “At the camp on the Banquet road no other Anopheles were taken … During the period covered by the prevalence of this insect, malaria was extremely prevalent, and practically the only disease present; while later, when this mosquito disappeared and the collections were mainly Culicines, the fever also had largely disappeared.” M. ludlowi was the only Anopheles from six other stations which showed prevalence of malaria. It is of great importance to determine if this mosquito does really carry malaria; the finding of zygotes in the stomach of specimens in the Andaman Islands by Major Christophers is just short of final proof of their culpability.

| 7.4 |

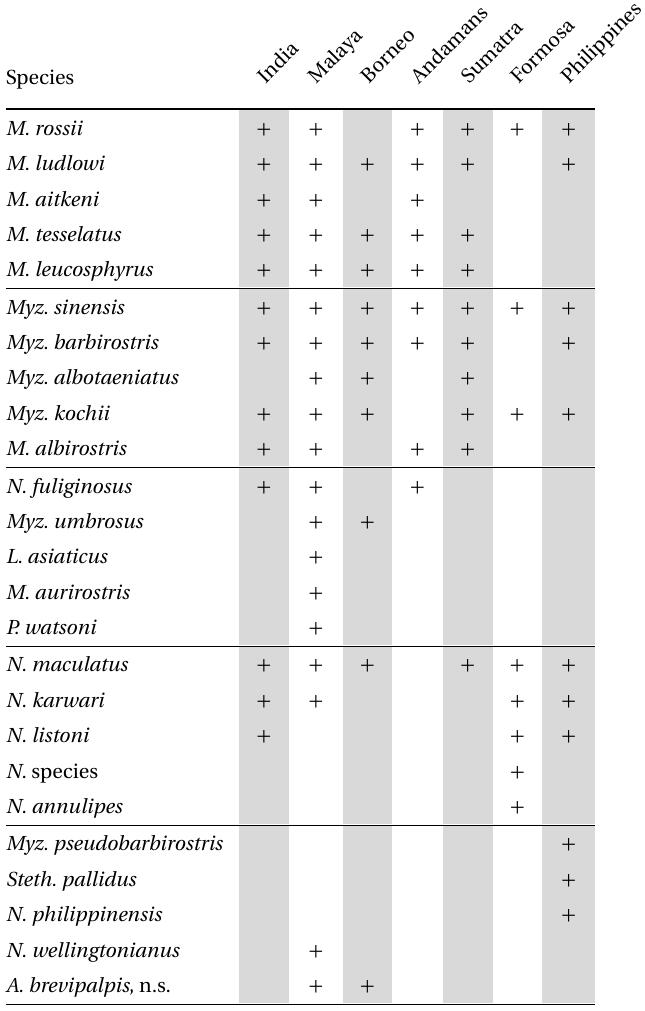

The distribution of Anopheles in South and East Asia |

It may be useful if I give here a list of the names and distribution of the Anopheles of South and East Asia. It is over fifty years since Alfred Russell Wallace returned from the Malaya Archipelago with 125,660 specimens of natural history. For eight years he had travelled from place to place, often enduring great hardship and privation. But these years made a great naturalist, and gave the world a wealth of scientific knowledge. Among the many interesting discoveries he made was the relationship which existed between the various islands of the Archipelago and the continents of Asia and Australia. He showed how the islands could be classed in three great groups: one which belonged to and, at one time, formed part of Asia; one to Australia; and a third group, consisting of islands formed by volcanic action, which were not continental in origin, although they may have been connected for periods with one or other continent. He proved this by showing how the various species of animals were distributed.

We are far from having anything like a complete knowledge of the mosquitoes of the Archipelago and the adjacent countries; but already we know something. From the table it will be seen that the Bornean group contain all the common mosquitoes of the Malay Peninsula, with the curious exception of A. rossii. It seems impossible that Dr Roper, who has made and identified (confirmed by Mr Edwards of the British Museum) the collection, can have missed A. rossii, if it is as common as it is in the Peninsula. A. umbrosus, found in the Peninsula, is also found in Borneo. This common mosquito population is a further proof of what Wallace discovered, that Borneo had been originally part of the continent of Asia.

We have seen, too, that in the south of Formosa a number of species exist, but that A. rossii, and presumably the others, except A. sinensis, do not spread beyond 24°N. lat. In Japan the only species I saw at the Imperial Research Institute was A. sinensis, and as malaria, due to the benign para sites, is found in Japan, this mosquito probably acts as a carrier of these forms of the disease. There is, however, strong evidence that it does not carry malignant or tropical malaria. Of Java, I believe nothing has been published of the relationship of the Anopheles to the distribution of malaria, except the papers of Dr De Vogel on A. rossii. It seems to me that from an investigation of the malaria in the islands of the Malay Archipelago much valuable information may be obtained.

Research cannot be confined to a laboratory; much knowledge can be obtained only in the field, and to the sanitarian the field should be a laboratory. If it is true that he cannot alter the conditions of his experiments, and so test the truth of his conclusions; he may, however, move to another place where the conditions are different, and there confirm or revise his previous conclusions. Thus to the sanitarian the world becomes a laboratory, and his experiments are carried out on a colossal scale. In the almost innumerable islands of the Archipelago, some may be found with particular groups of Anopheles, and by studying these groups and their relationship to malaria, it appears to me that information of great value may be obtained easily which elsewhere would be got only with extreme difficulty, if at all.