| 17 |

British Guiana |

| 17.1 |

Introductory |

Of British Guiana I had often heard from Dr Daniels, when he was Director of the Institute for Medical Research, Federated Malay States, and I was now looking forward with interest to my visit to it, even if it could be only a short one. In British Guiana Dr Daniels had demonstrated in 1895 that malaria affected young children, and that as they grew older they gradually became immune, an observation frequently, but wrongly, attributed to Koch. I was aware, therefore, that malaria existed in British Guiana. I had often heard, too, of how the Dutch had reclaimed so much of the land from the sea; of the sea defences, the great drainage canals, and the tide gates; of miles and miles of estates all below high tide level. It seemed an ideal country to test the theory that agriculture abolished malaria on flat land, and a special interest was given to the inquiry from the knowledge that the most important malaria-carrying mosquitoes of Panama were also to be found in British Guiana.

The sanitarian, pent up in the jungle at Panama, had seemed to be always on the defensive. True, it was a brilliant defence; but still the enemy had not been killed, and, if precautions were relaxed, would return in full force at once. What was the condition in British Guiana? Had agriculture attacked the enemy and driven it out, once and for all? This was the chief point I wished to determine; everything else was comparatively insignificant. If it was found that, where properly cultivated, British Guiana was free from malaria, then men might surely hope to control malaria in any land, in any part of the world. As my visit lasted only ten days, it will be best if I record what I saw from day to day, so that the reader may judge for himself the value of my views.

At daylight on the 13th June 1913, the S.S. Crown of Grenada was somewhere off the mouth of the Demerara River, rolling unpleasantly in an easterly swell. Nothing could be seen of the low-lying coastline; but at nine o’clock we sighted a lightship, picked up a pilot, and turned towards where the shore was supposed to be. That land could not be far off, we concluded from the muddy water through which we ploughed, and within half an hour we saw the tops of the trees and the higher buildings of Georgetown, which is situated at the mouth of the Demerara River.

British Guiana does not look much on a map of South America, but in reality it is a large country. It lies between the 1st and 6th degrees of north latitude, and longitude 59° west runs through it from end to end. Only the coastline, a low-lying belt 10 to 40 miles wide, has been opened up. Behind this comes “a broader and slightly more elevated tract of land composed of sandy and clayey, practically sedimentary soils,”82 in which sand dunes are to be found rising from 50 to 100 feet above the sea level. Behind those are three great ranges of mountains, and several smaller groups, the eastern portion of which is forest clad, while on the west there are extensive grass clad savannahs. Several large rivers traverse the land, but owing to numerous cataracts and waterfalls they are practically useless for navigation. For this reason railways are necessary if the country is to be opened up.

Having presented my letters of introduction, and said what I was specially interested in, the Hon. Acting Surgeon-General, Dr Rowland, kindly gave me all the reports available; and as great attention had been paid to the subject of malaria on the sugar estates for several years, I was at once put into possession of much valuable information. Of special value were the spleen rates of many estates taken in 1911, and charts and tables of the malaria admissions to estate hospitals, before and after systematic dosing with quinine had been begun. In the report on the spleen rates, I found that hardly an estate in the country had less than 50 percent of enlarged spleens, which indicated a high degree of malaria infection; but on the other hand the death rates were distinctly low. In the Report of the Immigration Agent-General for the year 1911–12, I found the percentages of mortality of the mean population during the year were as stated in Table 17.1.

| Group | Mortality (%) |

| Indentured labourers | 1.73 |

| Unindentured labourers | 2.53 |

| Children | 3.10 |

Such low death rates, where malaria was so high as to be represented by spleen rates of 50, did not fit in with my experience, and I was unable to understand it. Although the Courantyne coast was said to be the healthiest of all and freest from malaria, even there the spleen rates were from 15 to 60. The agricultural theory seemed to have broken down completely as regards the flat coast land, so there remained only the question of what would be found in hill land. There were only two hill estates in the country, both on the Essequibo River, and it was arranged I should visit one of these. As the steamer for the Essequibo did not sail until Tuesday, and this was Saturday, I had an opportunity of seeing something of Georgetown, under the guidance of the Hon. Dr Rowland, Dr K. S. Wise, and Dr E. P. Minett.

Georgetown, the capital of the colony, is on the low alluvial coast land, and is protected from the sea by sea defences, like other parts of the coast. Being in low, flat land, roads could be made only by excavating the adjoining land, so the town has a large canal or drain almost wherever it has a street. The streets are laid out at right angles to each other and are well kept; the public buildings and many of the private houses are handsome, and the town has good reason to be proud of itself in these respects.

On the 15th and 16th I examined various drains and trenches in the town. In the grass at the side of the trench in the centre of Carmichael Street I found many Anopheles larvae, some of which developed into A. albimanus. This trench was closed at each end by cross streets; in the next section it was being filled up. In a similar closed trench next the hospital no larvae were found, but this had the appearance of having just been filled by recent rains. Further along I came to a trench of another kind: it was deeper, and the level of the water was on a level with the road or nearly so; as I learned afterwards this was one of the canals which bring water into the town. Here a careful search among grass and debris failed to discover a single larva, nor was anything found in the large trenches on each side of the railway.

At Camp Street I turned towards the sea wall; many larvae were found among some dead leaves in an isolated stagnant pool by the side of the road; but in a large trench on the east side, where the vegetation was alive and the water cleaner, only a single small larva was found. I walked back by the sea wall, having confirmed what I had seen in Panama, that A. albimanus is very partial to the smaller collections of water and to debris. I had found larvae easily enough, and if they were always and everywhere as abundant, there was no difficulty in explaining the high spleen rates. It looked as if A. albimanus would always find a sufficient number of breeding places in any country in which it existed to ensure a safe passage for the malaria parasite from one man to another; in other words, that wherever A. albimanus existed at all, it would be so abundant that the place would be intensely malarious.

On the following day I resumed my search in the East Street trench, drawing a blank as before; nor was anything found in the canal, where a feathery weed was so abundant that battalions of larvae might have found shelter. The Lamaha Canal brings water into the town from the savannahs; it is raised above the level of the streets. On each side there is a small ditch; but in these no Anopheles larvae were found even in masses of fine algae, although Culex was common enough.

Wandering into the beautiful Botanical Gardens I was searching the lily ponds without capturing anything, when the superintendent captured me. I explained what I was looking for, and asked if in any of the other ponds there was more dead vegetation than in the one I was examining. I was then taken to a pond where sea cow (manatees) had eaten up all the vegetation; not a larva could be found. In the manatee, the sanitarian appeared to have found an ally, and he dilated on the idea of introducing it into all canals as an anti-mosquito measure. The botanist stood it for a time only, and then broke in, “But what about the aquatic vegetation?”

Calling upon Professor Harrison, Director of the Department of Science and Agriculture, whose house is in the Gardens, I met Mr Bancroft, late of the Federated Malay States Agricultural Department. He had only recently been transferred; indeed only six months before we had travelled together in the Federated Malay States, and now we had met on the opposite side of the globe, each having travelled in the opposite direction to the other. It was another instance of the friends a traveller meets in the most unexpected places.

In the evening Dr Rowland drove me six miles out the East Coast Road, where I had an opportunity of seeing more of the sea defences. The Coast Road runs parallel to, and a short distance within the sea wall, which here consists of earth without any stone facing. On the sea side of the wall mangrove is encouraged to grow, for it is a great protection against wave action. At one point the sea had recently breached the wall, and it had been rebuilt with a facing of greenheart, a fine timber whose home is British Guiana. On the inland side of the road no jungle or forest was visible; for the first few miles, indeed, the land was like a grass park, quite uncultivated, with negro houses dotted here and there, round which there were occasionally a few bushes. Further out we came to places where scrub had grown to a height of 20 to 30 feet, and the land had reverted to genuine swamp. Dr Rowland told me that all the land along the sea front had been under sugar at one time, but becoming impoverished, had been abandoned by the estates which now cultivated the land further inland.

In a country like what we were now travelling in, one expects to see borrow-pits by the side of the road; but here the number of such pits was quite extraordinary, in fact, the land along the road was literally honeycombed by borrow-pits for many yards beyond the original roadside drain. The reason for these pits is the impossibility of getting stone to metal the roads, consequently the surface of the roads has to be covered by burnt clay which is taken from the pits. As roads with any considerable traffic have to be re-metalled each year, it is easy to understand why so large a number of borrow-pits already exist; and unless some substitute for burnt clay is found, it is equally clear thousands of other borrow-pits will have to be dug. As those isolated borrow-pits are suitable breeding places for A. albimanus, the upkeep of the roads which is necessary for the public convenience appears to be in direct conflict with the public health. Indeed, the Medical Department had already represented this to the Department of Public Works; but having discovered that it was only isolated borrow-pits that were dangerous, the recommendation was that all borrow-pits should be connected up with the roadside drains. I have no doubt that as the advice of the Medical Department is sound, it will be followed in time; but as far as I could make out, no attention had been paid to the recommendation so far.

After visiting a negro village, the name of which I have forgotten, and seeing how the negro, like the Malay, allows his house to be smothered in fruit trees and weeds, we turned back to Georgetown. It was now getting dusk, and I then experienced the attacks of Culex taeniorhynchus for the first time. Although our horse was being driven at an ordinary running pace, the Victoria was full of the mosquitoes, and we were constantly being attacked. These mosquitoes were so abundant at times, so I was told, that if a donkey was left out in the fields all night it would be found dead in the morning. At the time I did not feel called upon to do more than listen to this tale; but before I left British Guiana, further acquaintance with this mosquito made me believe it capable of any crime.

| 17.2 |

Breeding places of mosquitoes in Georgetown |

An examination of the mosquito breeding places had been carried out in 1910 and 1911 by Dr Wise, whose report was published,83 and from that paper I extract some of his observations:

The Anopheline mosquitoes (nearly always Cellia albipes,84 occasionally Cellia argyritarsis were found breeding in nearly all trenches where overgrown with vegetation, both in the city and environs. Where no vegetation was permitted no Anopheline larvae were discovered. These mosquitoes were also found breeding in the hollowed-out stumps of trees which had been cut down in the lots and by the roadside. Numerous Anopheline larvae may be found during the rainy seasons, in the small grass-grown cross drains of the Queenstown district. They may occasionally be met with in cocoa nutshells, and in the grass-grown pools and trenches around the barracks.

This certainly was not very hopeful reading; it looked as if the whole colony would have to be “clean weeded,” as we say in the Federated Malay States (i.e., to have all aquatic vegetation removed), if malaria were to be abolished. Since the operation would have to be repeated about every two or three weeks, it would not be possible to do it, and the prospects of eradication of the disease hardly seemed worth discussing.

Of the breeding places of other mosquitoes Dr Wise also gives a description. The great breeding place of Aedes calopus (i.e., Stegomyia fasciata, the yellow fever carrier) is the water vat which is attached to each house. The water supply for the town comes in an open trench, the Lamaha Canal, from an empoldered area ten miles from the town. It is a peaty brown water, and is not used for drinking or cooking. Drinking water is “collected from the roofs, and conserved in large wooden vats and iron cisterns. Of these vats, 63.9 percent were effectively screened. One thousand three hundred and ninety-six vats had more or less defective covers nullifying any beneficial effect of screening.” In the examination 2560 premises were entered and examined, and of these 1490 were found breeding mosquitoes somewhere at the time of inspection. Dr Wise makes special note of the amount of scrub in the city, and of how this conceals tins and other breeding places.

In another paper Drs Wise and Minett deal critically with “Rain as a Drinking Water Supply in British Guiana,”85 and show that

- 1.before rain the water is good;

- 2.just after rain a great pollution occurs, and the water is totally unfit for consumption;

- 3.pollution slowly disappears, till from the fourteenth day onwards the water is again fit to drink.

There are two chief reasons for the pollution of the tanks in Georgetown; one is the carrion crow, which, picking up the “most indescribable filth and carrion,” takes it to the roofs of the houses, and there eats it; the other is, that many of the water receptacles are simply leaky old iron tanks sunk in the ground, often close to cesspits.

As typhoid fever is far from uncommon at present, and yellow fever may at any time arrive to sweep through a population which has been free from it for almost a generation, Georgetown is certainly sitting on a volcano. The water problem is acute, but no less is it difficult. It may be possible to purify and decolorise the Lamaha supply so as to make it fit for drinking; the deep bore now being put down may find good water; or it may be necessary to go inland to the hills for a pure supply. The authorities are fully alive to the gravity of the situation. They are determined to solve the problem; but it is far from an easy one, either physically as regards the source of the water, or financially in regard to the money, for this is complicated by the Constitution of the colony.

When British Guiana came finally into the possession of the British in 1814–15, the land was cultivated by slaves, and this continued to be the labour until the Emancipation in 1834 brought the planters face to face with ruin:86

Continuous and steady work was what the planter required, and this was just the thing the free negro was incapable of giving. The planters, faced with ruin, had recourse to immigration, and the history of the development of this system from its first crude efforts, through its many and sometimes almost fatal mistakes, to the present day, when it has been justly described as a model for all the world, makes an interesting study.

I do not propose to follow that at the moment, beyond remarking that the Emancipation upset the system of taxation which had been “a certain sum per head for each slave,” and that for many years the Government had difficulties in getting their “supplies” voted; ultimately, in 1891, the Constitution was changed; votes were given to every male person who possessed certain and not very restrictive qualifications, and the financial power of the country passed from the hands of the Governor. How the experiment will work out in the end, I do not propose to speculate about, but the immediate result is that since the Governor cannot guarantee the security, the Colonial Office will not approve of loans, without which it is impossible to carry out great public works, like water supplies and railways. How strangely different this history is from that of the Federated Malay States.

| 17.3 |

The Hills Estate |

On Tuesday, 17th June, I started off in one of Sproston’s steamers for the “Hills Estate” on the Masaruni River, one of the tributaries of the Essequibo. The sail was interesting, but I need not describe it. On arrival at the estate, I discovered that the manager, Mr Withers, had been in the Federated Malay States in the early days, so we had much to talk about. I made a careful examination of a number of drains on the estate, especially those at the foot of a hill near to some nurseries, but neither there nor in any other drain on the estate did I find a larva, even among the grass which grew in some of them. The land was undulating; in the Federated Malay States it would have been very unhealthy; but there was no history of fever on the estate, and Mr and Mrs Withers and their little girl certainly did not look the victims of the disease. As the labour force consisted largely of adults, I made no spleen examination.

On my return journey, I left the steamer at Tuschen, and trained to Georgetown, or at least to the opposite side of the Demerara, so as to get a view of the country.

| 17.4 |

Flat Coast Land Estates |

On the 19th Dr Wise took me to Plantation Uitvlugt by motor car, on the way to which we passed Gladstone’s Estate “Vreed-on-Hoop,” about which controversy raged so fiercely at the Emancipation time. The road to the estate had a good surface, was dead level, and so should have been good driving; but unfortunately the devils of China seem to have come to British Guiana and made the roads with a maximum number of turns, so that they could practice turning, which is said to be to them an almost impossible operation. Anyhow, whether the Chinese devils inspired it or not, the road took a right angle turn every few hundred yards, and we progressed by taking three sides of every block we came to. Visitors are told the reason for these turns is that the road follows old estate roads which were always either at right angles or parallel to the sea. That may be so; I prefer the Chinese devil theory, it is more in keeping with one’s mood after a motor run on such a road.

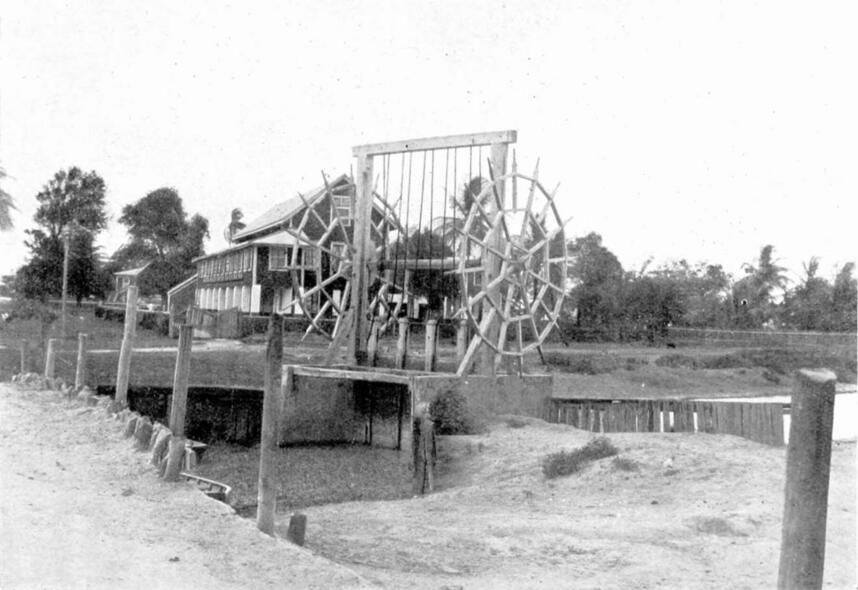

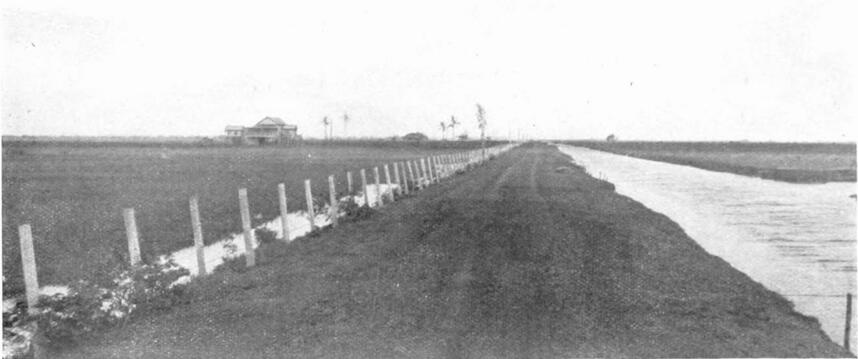

All the estates on the coast are of the same shape, and their irrigation and drainage systems are easily understood. When the Dutch began sugar cultivation and wanted to make estates, they threw up a polder or dyke close to the sea, below high-water mark, to keep the sea out. About four miles behind this they built another dyke to keep the estate from being flooded from behind, and also to dam up water for their irrigation channels. They threw up banks about every half mile at right angles to the sea, which cut up the land into estates about four miles deep and half a mile wide. To drain the estates large drains were dug down each side boundary; a number of subsidiary drains at right angles to these were also cut, but the latter did not run from side to side of the estate for a reason which will be apparent in a moment. As the outlet of drains was below high-tide level, large tide gates called “kokers” were built; these were opened during ebb tide, and closed as soon as the seawater attempted to flow into the estate. They were worked by hand.

In addition to the drainage system, which takes water off the estate, another system of channels brings water in from the empoldered area or swamp behind. The quantity of water admitted is regulated by a gate, similar to the “koker” on the outlet. It flows in a main channel down the centre of the estate, and the subsidiary irrigation channels gridiron with, but do not connect with, the subsidiary drains. In this way the water level of the estate is under complete control, which is essential in a crop like sugar. The irrigation channel is also used as a navigation channel for the barges which bring the sugar canes from the field (“cane piece” is the curious local name) to the factory; water transport is a valuable means of reducing the cost of handling so heavy a product as canes.

As I have said, all the estates are the same, but many have abandoned the fields nearest to the sea, and many of them are now growing rice under the care of the East Indian population who have settled permanently in the Colony.

| 17.5 |

Uitvlugt Estate |

I had chosen to visit this estate because in the Surgeon-General’s report the statistics showed its spleen rate to be very high (see Table 17.2).

| Month | Spleen size | Ages | |||

| 1–3 | 4–8 | 9–12 | Total | ||

| January | Normal | 29 | 14 | 4 | 47 |

| Enlarged to edge of ribs | 34 | 66 | 31 | 131 | |

| Enlarged from edge of ribs to umbilicus | 17 | 67 | 30 | 114 | |

| Enlarged beyond umbilicus | 6 | 21 | 13 | 40 | |

| July | Normal | 60 | 102 | 50 | 212 |

| Enlarged to edge of ribs | 46 | 150 | 57 | 253 | |

| Enlarged from edge of ribs to umbilicus | 18 | 83 | 45 | 146 | |

| Enlarged beyond umbilicus | 2 | 15 | 4 | 21 | |

In January, no less than 285 children out of 352 or 85 percent had enlarged spleen. At the later examination in July, a much larger number of the children had been seen; few could have escaped, and the result was to show that out of 632 no less than 420 or 66 percent suffered from enlarged spleen, or in other words from malaria.

The figures given in the special malaria report showed that malaria had diminished very remarkably in the past few years, subsequent to the distribution of quinine; and Dr Wise furnished me with the figures given in Table 17.3, which are more complete than those given in the special report, inasmuch as they give the population each year instead of an average.

The diminution of the fever rate was most satisfactory; that it had been the result of quinine in doses which averaged only ten grains a month to each of the whole population appeared to me very remarkable when the high spleen rate is taken into account. In the Report of the Immigration Agent-General for 1911–12 the number of deaths for Uitvlugt is given as 60, which on a population of 4659 gives a death rate of 12.8 per 1000. The total cases admitted to hospital for the year was 2090, and 18 were treated as outpatients.

I was completely at a loss to understand these figures. With a spleen rate of 60 the death rate in the Federated Malay States would have been over 100 per 1000, and I had poured 20 grains of quinine a day into coolies for months without getting results that even distantly approached the Uitvlugt figures. Nor did the explanation of the mystery appear any nearer when, out of about forty or fifty children Dr Wise and I examined, only four had enlarged spleen. I then asked the native medical officer how spleens were examined on the estate. He said the child was laid flat on the table, and the spleen was then percussed. It was recorded as enlarged if the area of dulness was over the normal, even if the spleen could not be felt.

| Year | 1906–7 | 1907–8 | 1908–9 | 1909–10 | 1910–11 | 1911–12 | 1912–13 |

| Average population | 3444 | 3794 | 4101 | 4501 | 4593 | 4659 | 4678 |

| Fever cases | 2371 | 1522 | 1104 | 1054 | 797 | 553 | 142 |

| Oz. quinine distributed1 | – | – | – | – | 747 | 1965 | 1285 |

- 1

- Quinine distribution not recorded before 1910.

Here then was the explanation. In order to overlook no enlarged spleen, the greatest care had been taken in the examination; but unfortunately as this is not the method of examining and recording enlarged spleens in other countries, it gives a wrong impression to those who record as enlarged only what can be felt by the hand. To adjust the difference it would be necessary to exclude probably all those recorded as “enlarged to edge of ribs,” and perhaps some of the next group “enlarged from edge of ribs to umbilicus,” for foods in various parts of the intestinal tract would give a dull note to percussion which might have been interpreted as enlarged spleen. If we include in normal the group recorded as “enlarged to edge of ribs,” the spleen rates drop at once from 85 and 66 to 46 and 26; while if part of the next group is included they come to nearly what Dr Wise and I found, about 10 percent. If this was the correct interpretation of the figures recorded, then the whole mystery was solved. Malaria did exist, but to only a small fraction of what the recorded spleen rate would indicate; and of course where malaria is not intense, quinine gives the excellent results which had in fact been obtained.

In a moment the whole aspect of the malaria problem had altered. The spleen rates of the whole country had probably been obtained in this way; they had in fact been recorded as much higher than they really were, and when they were properly discounted, the low death rates would be explained. With the high spleen rates went the fear that malaria would never be overcome; that A. albimanus would never be driven out by agriculture; that it would never be possible to free the people of British Guiana from this pestilence.

The hospital is built on pillars 10 feet high. The floor is of wood. Beds with mattress and blankets are arranged in four rows up the ward. Male and female patients are separated by a partition. Separate wards are not provided for patients of different nationality or dysentery cases. The staff consists of a sick nurse and the usual complement of attendants.

| 17.6 |

Plantations: Diamond, Providence and Farm |

In the evening I visited this group of estates which are situated along the east bank of the Demerara River. They are under Mr Fleming, as attorney and general manager. Dr Fergusson, the medical officer of Peter’s Hall district has paid special attention to the coolies, dosing them systematically with both thymol and quinine, and their health is good. Mr Fleming has also given the medical officers strong support in their efforts to lower the death rates of his plantations. On Plantation Providence a most efficient latrine was devised; it is a corrugated iron shed placed over one of the small lateral drains of the estate. Unlike the others this drain is connected with the irrigation trench by means of a 6-inch pipe, consequently it is constantly flushed and never becomes objectionable. This form of latrine has been adopted by a number of other estates. Next to a proper sewer system, this is the most satisfactory way of dealing with the night soil of a native labour force.

On one of this group of estates I saw a large tank or well, surrounded by wire netting; the coolies draw water from it by means of a small semi-rotatory hand pump.

| 17.7 |

The Courantyne |

In a much more hopeful spirit, I sailed the same night for New Amsterdam to visit the Courantyne coast, which was reported as being the healthiest part of British Guiana. I was also anxious to meet the Rev. James Aitken, who with Dr Rowland had made such valuable and extensive investigations into the mosquitoes of British Guiana, that the insects of that region are better known than in nine out of ten places in the tropics. Arriving at daylight I was met by Mr Aitken, and discovered in a short time that we had been fellow students at Glasgow University more than twenty years before.

Mr Aitken told me that he had been in British Guiana for nine years, during which period he had had only two attacks of fever; the first was six years after his arrival. His wife had been seven years in the country and had never been attacked. He told me that after a drought in the previous year which had killed out the fish in a pond in his garden, A. albimanus had appeared in it in large numbers. It was quite exceptional to find larvae where there were fish. There were certain places containing water where he had never got larvae, such as the large trench behind the town; for over a year he had made constant observations of it without ever getting larvae. I saw this trench later in the day; it was full of vegetation, and at first sight appeared to be an ideal place for larvae, but I found none.

After seeing Mr Aitken’s collection of insects, and satisfying myself that his C. albipes was identical with A. albimanus of Panama, we started in a motor car for Port Mourant. The country was absolutely flat, and in places was beautiful open grazing land for miles at a stretch. During the American Givil War it had been under cotton, but when the war stopped, so did the cotton growing, and now it is just possible to trace the lines of the old drains. In wet weather it becomes a lake, but it dries evenly, and does not breed Anophelines, so I was told. The existence of bush giving shade to a pool favours larvae. At several places we searched the roadside drains for larvae but found none; there were, however, numerous small fishes. The roadside drains were full of grass, as they are in other flat countries with heavy rainfall.

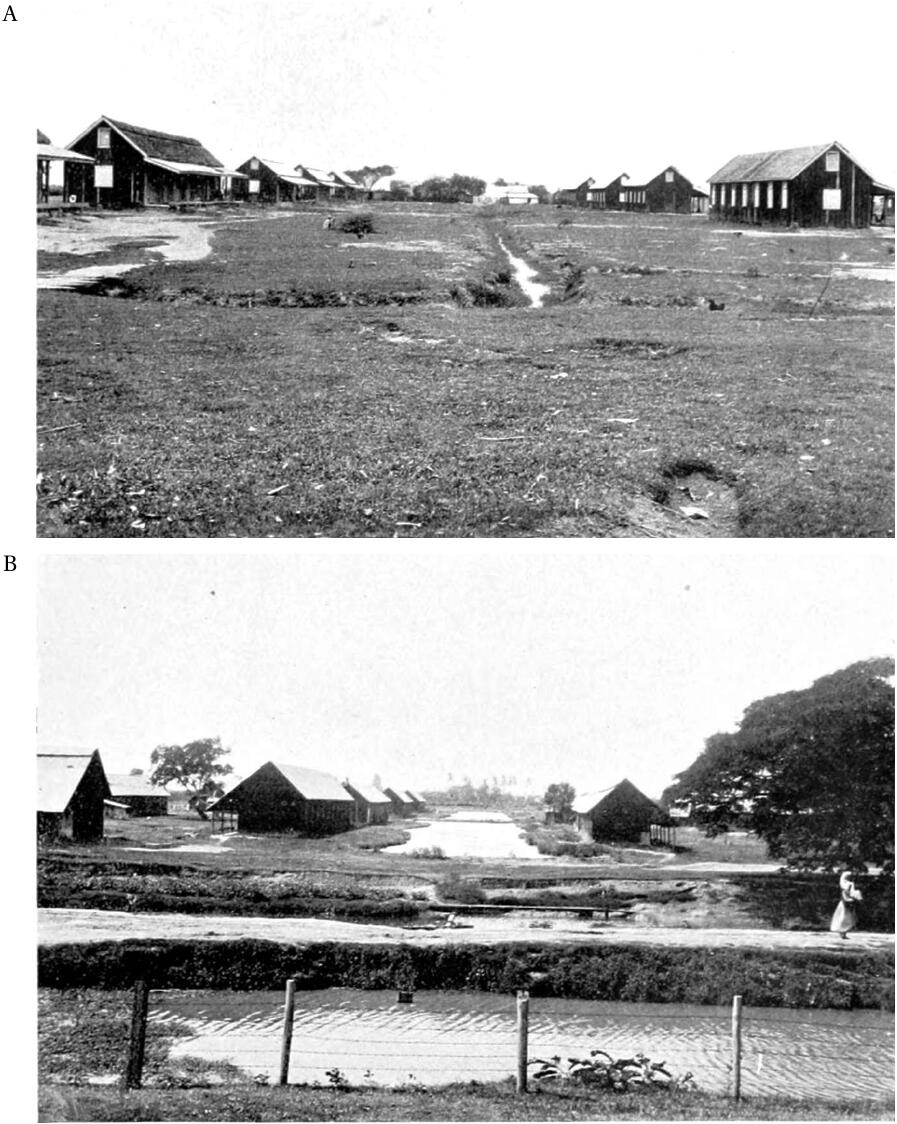

At Port Mourant, we breakfasted with Dr Kennard. His house is on the side of some rice fields, and in his compound there is a drain which he says does not breed Anopheles if cleaned out about twice a year. After breakfast we walked through the rice fields, which had just been planted, to the “nigger yard” of Plantation Port Mourant. This is divided up into the “indentured yard” and the “free yard.” The former conforms to the Government regulations; the buildings are all of the approved type plan, and the yard is under a short grass. The free yard shows the labourers’ capacity for architectural variety and town planning: huts and shacks built anyhow and anywhere would be another way of putting it. In the free yard, rice swamps and houses are more or less mixed up; the indentured yard had no swamps actually in it, but immediately over the fence and within 100 feet of the nearest buildings there was a stretch of 3000 acres of rice swamp.

| Year | 1906–7 | 1907–8 | 1908–9 | 1909–10 | 1910–11 | 1911–12 | 1912–13 |

| Average population | 5060 | 5228 | 5275 | 4328 | 4462 | 4612 | 4727 |

| Fever cases | 461 | 618 | 243 | 383 | 193 | 57 | 65 |

| Oz. quinine distributed1 | – | – | – | – | 1001/4 | 388 | 463 |

- 1

- Quinine distribution not recorded before 1910.

With such conditions present, one would have expected to find malaria severe, but the actual figures were as listed in Table 17.4. It would be difficult to find a place in the tropics much freer from malaria than this, for it must not be forgotten that immigrants may bring fever with them. It is much better than Panama at the best.

The spleen rates, however, were not so satisfactory as officially reported, and were as listed in Table 17.5. These figures give rates of 8 and 20 percent; but if we apply the correction which I suggested as regards Uitvlugt then the rates drop to under 2 both in January and July, and I suggest that this is the correct spleen rate.

| Spleen size | January | July |

| Normal | 137 | 133 |

| Enlarged to edge of ribs | 10 | 34 |

| Enlarged from edge of ribs to umbilicus | 2 | 3 |

| Enlarged beyond umbilicus | – | – |

Leaving the estate, we visited Rosehall school, where among 56 children not an enlarged spleen could be found.

Plantation Albion was a mile farther on. The coolie yard was a short distance in from the road: it was like all the others. The coolie lines or ranges are buildings partitioned into five or six rooms; each room is 10 feet by 20; this includes the 6-foot verandah. The floor is a mixture of cow dung and whiting, and the coolies are compelled by law to keep it in good order. In the middle of the coolie yard is the “sweet water” trench or pond. It is filled from time to time from the navigation trench. The sides are grassy; it is not enclosed in any way, and when a coolie wants water he takes his own dish and dips into the trench.

Although the trench is open to dangerous pollution, the statistics of the country show that these open water supplies are much less dangerous than many would have us believe, and the experience of this estate has been the same as mine in the Federated Malay States: that where malaria is absent high death rates are quite exceptional. Of course were cholera to appear in the country, these drinking trenches might easily become polluted and cause devastation of the labour force; but that disease has fortunately been rarely imported to British Guiana in the past. It is not endemic, and since the time when coolies first came by steamer from India it has not appeared, nor is it likely to appear in the future.

The photograph in Figure 17.7B show the drinking-water tank as well as other collections of water which might be expected to breed Anopheles, but, as a matter of fact, we found none; nor in such places are they to be found. The trench in the foreground was full of a floating weed which had been blown by the wind to the end of the trench (the left of the photograph). It looked as if it might have harboured Anopheles; we found only Culex larvae, but these were in abundance. In all pools I was on the lookout for algae such as were specially associated with A. albimanus in Panama, but I saw none. Is the water of British Guiana not suitable for the growth of this particular kind of larvae food? Yet that can hardly be the sole cause of the absence of Anopheline larvae from the trenches; and if fish destroy Anopheles larvae, why do Culex escape?

Whatever is the explanation, there can be no doubt that malaria is by no means common on this estate. The figures for Albion are given in Table 17.6.

| Year | 1906–7 | 1907–8 | 1908–9 | 1909–10 | 1910–11 | 1911–12 | 1912–13 |

| Average population | 3750 | 3613 | 3325 | 3569 | 3511 | 3411 | 3532 |

| Fever cases | 900 | 935 | 803 | 1755 | 846 | 338 | 364 |

| Oz. quinine distributed1 | – | – | 100 | 162 | 481 | 649 | 1266 |

- 1

- Quinine distribution not recorded before 1908.

In 1911–12 the total admissions to hospital from all causes was 2368; the outpatients numbered 532. At the hospital I saw about a dozen coolies whom Dr Kennard called “loafers.” There was nothing really the matter with them; they had learned that the hospital is a comfortable place and preferred staying in it to working. Being indentured coolies, they are sent to hospital if they do not work, and it is not always easy to prove to a magistrate such people are really shamming. The “loafer” is a difficult problem in all countries; but the fact that the percentage of convictions to the total indentured population amounted to 14.7, 35 percent of which were cases of habitual idleness, shows the employers of British Guiana are imposed upon by a considerable number of coolies; and such a gang as I saw swell the admission rate to hospital without representing any real ill-health. If any further proof of the excellent health of this estate were necessary, it is in the fact that the death rate for 1911–12 was 11.1 per 1000.

In the Surgeon-General’s Report I find the spleen census given in Table 17.7. These figures give spleen rates percent of 14.2 and 12.4. If we make the correction I suggest, they become less than 1 percent in January and zero in July.

Visiting the plantation school, I examined 113 children. One only had enlarged spleen, and the enlargement was very slight. On the way back we stopped at a school about a mile out of New Amsterdam. The pupils had left, but 19 were called back and examined; not one had enlarged spleen. In all I examined 188 children on the Courantyne coast, finding only one with enlarged spleen.

In the face of all the foregoing figures, it is clear that in this part of British Guiana agriculture has, in some way, for all practical purposes extinguished malaria. One thing is certain. Malaria has disappeared not because the pools, drains, trenches and rice fields have been oiled or weeded; not because the inhabitants have lived in screened houses; not because any of the subsidiary Panama methods have been employed to kill Anopheles adults or larvae. The country is non-malarious because the malaria-carrying Anopheles do not breed in the water in land which is cultivated in British Guiana.

Need I emphasise the importance of realising this? Confirming as it does similar experiences in the fiat land of the Federated Malay States, it means that in most tropical lands malaria will disappear as they become developed, without the special measures or organization found necessary in Panama where no cultivation has been allowed.

| Spleen size | January | July |

| Normal | 325 | 281 |

| Enlarged to edge of ribs | 51 | 40 |

| Enlarged from edge of ribs to umbilicus | 2 | – |

| Enlarged beyond umbilicus | 1 | – |

| 17.8 |

Rice fields in British Guiana |

Of late years the Indian population has cultivated rice, and in 1911–12 the total area in the colony under this crop was 36,000 acres. To the colony it is a great asset, and it is looked upon with favour by the Government and the plantations in view of the uncertain future of the sugar industry. On the other hand, the medical men, bearing in mind the serious consequences which have followed the cultivation of rice in other countries, have looked upon the extension of rice cultivation with great anxiety. In a valuable paper entitled “Rice Fields and Malaria,” Dr C. P. Kennard gives his views and experiences.87 After referring to the views of Celli and Koch, who hold that rice fields produce or aggravate malaria, he says: “Of late years there has been a marked increase of malaria fever on this coast, coincident with the great extension of the rice industry there; beyond this increased rice cultivation there has been little change, drainage, other agricultural pursuits, and methods of living remain much the same.” He then describes the process of rice cultivation and how Anopheles may live in the rice swamps. Then he goes on: “The question now arises, do the people living among the rice fields suffer more from malaria than elsewhere?” and the emphatic answer is given: “This is undoubtedly so.” He then goes into the question of the time of year when malaria is at its worst; it would appear to be in September and October, when rice is being reaped. He also observed that when new fields are being brought under cultivation, malaria is more severe. He gives some figures relating to hospital admissions (see Table 17.8)88 and comments:

| Month | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 |

| July | 71 | 153 | 46 |

| August | 72 | 198 | 73 |

| September | 132 | 260 | 77 |

| October | 111 | 311 | 118 |

| November | 95 | 336 | 159 |

| December | 58 | 133 | 107 |

| January | 46 | 66 | 66 |

The marked rise in 1909 is attributed chiefly to a new settlement among some new rice fields, and the rise commencing early was probably due to some plots of land not being taken in, so that when irrigation occurred over the rest of the fields, with the rain, suitable pools were kept up in these plots among the bush, and in the immediate neighbourhood of the houses.

Dr Kennard finds “some consolation in the fact that the people who have lived for some years in the rice fields settlements become more or less immune from malaria,” although he would have us remember that “not only are these settlements a danger to themselves but to the general community.” Knowing that 66,000 acres of rice swamps in the Krian District of the Federated Malay States are practically free from malaria, and that the labour force at Port Mourant in British Guiana is practically free from malaria, although it lives on the edge of an extensive rice field, I have much less fear of rice cultivation than Dr Kennard, and find in his own most valuable observations, which I am now about to print in extenso, the true way to prevent them ever becoming harmful.

The Anopheles require shade to breed in. I have seen pools teeming with mosquito larvae in the open, but no Anopheles larvae there, although Anopheles were in the neighbourhood. They also require more or less clean water and absence of fish; fish will soon eat up any mosquito larvae they come across. When the rice is growing and the land is submerged, fish are all about, and I have never been able to find larvae among the growing rice in this condition.

Some time back I was in a field which was covered with water and the rice nearly ready to cut. In this part of the field I could find no larvae, but many small fish. I also came across no Anopheles. In a part of the field where the water was drying up preparatory to the rice-cutting, small pools had been left in the depressions, and from two or three of these pools among the growing rice I was able to collect Anopheles larvae (from which I developed later on an Anopheles of the usual variety seen here, A. argyritarsis or A. albitarsis); at this spot I also came across two or three adult Anopheles. In a couple of days these pools were dry, so most of the larvae did not develop; but a little rain falling would have kept up the pools so that the larvae would have reached maturity.

We have in that field a natural exhibition of what occurs in the rice fields generally—land submerged, fish present, no Anopheles—land drying up, clear pools with shade, no fish, Anopheles. We have therefore about the rice-reaping time a great increase of Anopheles bred under the favourable conditions above mentioned, and I need not point out that the absence of rains—heavy rains—irregular irrigation or drainage, or irregular level of land, will all make a difference in the formation of pools suitable for or against Anopheles breeding, and so varying local circumstances and effects; as for instance, land drying up with enough rain falling to keep up the pools, but not to flood the land, would be the most suitable for Anopheles breeding.

Anopheles can also breed in the trenches connected with the rice fields if these have much weeds and growth; the fish prevent their multiplying much, but a few of the larvae may escape to develop to maturity. I have found a stray Anopheles larva with other mosquito larvae in such trenches. The trench on one side of my field is connected with the rice fields which surround it on two sides. At the early part of the year I had the trench weeded and all rushes cut down, and whereas previously I could nearly always find Anopheles in the house, since then they have been distinctly rare. It may be thought that, as the water drains off, enough fish would be left in the pools to destroy the larvae, but this is not so. When the water is going off the fish go with it mostly; they leave these small holes, but may remain in the larger ponds and depressions.

On these observations he frames the following rules:

Firstly, no settlement shall be allowed in the rice fields.

Secondly, no rice fields should be within 200 yards of the houses to the leeward, or within a quarter of a mile to the windward. The Anopheles is not a strong flyer, but is said to be able to travel at least over 100 yards. In Italy I believe there is a law preventing rice fields near the houses.

Thirdly, the trenches connected with the rice fields should be kept clean and free from weeds, and the excess of water be properly conducted away from the fields and not swamping the surroundings, as is frequently seen and is one of the worst features in the rice fields near the villages; some of the villages are kept in a bad state of drainage or irrigation owing to this, and thus local foci for Anopheles breeding may be developed and kept up.

Fourthly, the rice should be planted in each field or fields under the same common drainage or irrigation at the same time, so that it would be reaped at the same time, and the water could be regulated accordingly; thus there would be fewer pools about, and these would exist during shorter periods.

Fifthly, at the time of reaping everybody working in the rice fields should take a daily dose of quinine; and in the rice settlements, if not abolished, they should commence this earlier and continue for a little time after the rice reaping.

These methods I am sure would do away with a good deal of malaria in connection with the rice fields; they would not do away with it altogether, as there would still be the other influences unconnected with the rice fields in operation. I think, however, they would have the effect of restoring the Courantyne coast to its previous reputation of having little malaria, and with an increased population, better drainage, and other general anti-malarial precautions, this should be one of the first parts of the colony to get rid of the disease. As I have already said, I have dealt with the Courantyne coast as it is particularly known to me; the other parts of the colony must be affected by their rice fields in the same way and require the same precautions.

I am not prepared to endorse the statement about the flight of the Anopheles, and the restriction of dwelling houses to certain distances from swamps; but otherwise the regulations suggested appear to me to be exactly what is required; and if they are followed, British Guiana need have no fear of the extension of so valuable an industry as rice cultivation.

| 17.9 |

The Future |

When the estates had just been opened up they had been unhealthy, and when the Indian coolies arrived to reopen the partially abandoned estates, their health had been most unsatisfactory. But as the years passed and good hospitals were established, the health became good, and the improvement was put down to the improved hospital system. I take leave to doubt this. I believe these estates were very malarious when first opened, and became so again when partially abandoned; but the improved health was in my opinion due to the land being put under cultivation; it was cultivation that drove out malaria.

It is true that on some of the estates malaria exists. It is shown by the lowered admission rates after quinine came to be administered more systematically; but I believe that the real way to eradicate the malaria is to eradicate the mosquito. Much is already known about the malaria-carrying mosquito in British Guiana, which should tell the medical officer where to look for it when he proposes to carry out an anti-mosquito campaign on an estate. The danger is in the smaller pools rather than the large trenches; and if Port Mourant with its 3000 acres of rice fields is so free from malaria, it should not be impossible to bring other places up to the same standard, or even improve on it.

On the medical officers of British Guiana there is a great responsibility, as for them there is the great opportunity of conferring lasting benefit on the colony. The work must be done in the field and the village, not in the hospital, and the knowledge of the scientist must be yoked to the wisdom of the man of the world. Only in this way can be supplied that urgent need of British Guiana—a great industrial population. Although the estate coolies are healthy, the negro in his hut—built on a half-drained compound and smothered in bush—is far from being free from disease; and the infantile mortality is so high that the negro population is actually decreasing. The high infantile death rate is indeed the negro’s chief asset; it keeps wages so high that if he works for a day he can retire to his hut for a week.

Before the days of beet, a sugar estate in British Guiana was a valuable property, both to the proprietor and to the colony. But the days of prosperity are gone. Now with the most rigid economy, the estates can just make ends meet; in a bad year there may be serious loss. Without the Indian coolie the estates could no longer be carried on. Provided with a comfortable home, cared for in a hospital when sick, and given what to him is a princely wage, the coolie has made a good bargain when he comes to British Guiana, and a population of over 120,000 East Indians shows he knows it. No less is it a good bargain for the estates. If there were no Indian coolies, no work could be done, and the estates would have to be closed. To the proprietors it would mean ruin; to the colony, the loss of most of its white population. If that occurred, it is difficult to see what is to prevent the negro, if not extinguished by disease, from relapsing almost into his original savage state, for the power of the Government would diminish as the country became more and more swallowed up in jungle.

I paint no fanciful fear. Ever before the planter is the fear that the Indian Government may prohibit immigration; it has been done before. But if from the existing material—the Negro and the East Indian—the medical officers build up a strong, healthy population, so abundant that it must work to live, and the healthier because it must work, then truly they will have saved British Guiana from barbarism and given it a place in the sun.